Codebreaking our future

High noon in East Asia: the coming implosion of North Korea

3 August 2016 by Admin in Codebreaking our future, Current events

By Michael Lee, author of Codebreaking our Future

There is more to the current war of words between North Korea and the US–South Korea alliance than sabre-rattling. After its northern neighbour conducted its most powerful nuclear test yet, triggering a magnitude 5.3 earthquake in the process, South Korea promised to ‘annihilate’ Pyongyang if there is even a hint that its neighbour is about to begin a nuclear war. A tense and beleaguered South Korea is now preparing for what it calls a ‘worst case’ scenario. But how realistic is this potential future?

North Korea seems to be edging ever closer to its long-term goal of mass producing nuclear warheads.[1] A deadly cat-and-mouse game is underway, one which is starting to resemble the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962. But the Korea crisis of today seems even more dangerous, because we’re talking about the potential for both nuclear and conventional warfare. The border between the two Koreas is the most militarised place on earth, heavily lined with missiles. In addition, the United States Forces Korea (USFK), under the United States Pacific Command (USPACOM), has about 28,500 American soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines stationed in South Korea. This situation could get very messy indeed. A confrontation could easily be triggered. Once again, the world is on edge as it was back in 1962.

From our vantage point in the West we can see that North Korea is trapped in a time-warp, a kind of living museum of 1950s style Cold War socialism. I believe that North Korea is a state on the edge. Its collapse is almost inevitable, but the form it will take is less clear.

The current dictatorship cannot last, in fact, I see North Korea becoming a colony, or puppet state, of China (more on that later). This colonisation could prevail until the new Asian superpower has evolved into a freer civilisation and ceases to see the US as a major strategic rival in East Asia. When this region is no longer the flashpoint of economic and ideological competition between a waning but powerful global empire – the USA – and the rise of China, the two Koreas will finally be reunified like Germany was in 1990.

Korea will then be truly free for the first time since Japan annexed it in 1895.

So where is the evidence for this scenario? The idea of North Korea imploding is plausible. In fact, the country almost collapsed completely in the 1990s after the fall of the Soviet Union. It only survives today because it offers a convenient buffer state for China against American military presence in South Korea, Japan and Australia.

By looking at Korea’s history we can get a glimpse into the future of the country. At the time of the partition of Korea into North and South Korea,[2] the former was largely industrial and the latter agrarian. While South Korea advanced in the intervening decades into a leading Asian Tiger economy, its northern counterpart descended into a dystopia begging to be captured on celluloid. It is a story of two Koreas: to the north, economic decline of an industrial society brought about by an energy crisis coupled with ecological degradation, and, to the south, economic prosperity and technological innovation catapulting an agricultural society into the twenty-first century.

The fact that North Korea fell so hard after the collapse of communism shows the extent to which this small nation has relied upon foreign supplies. Since the Korean peninsula as a whole has little oil and gas of its own, communist North Korea depended upon the Soviet Union for its industrial energy needs until that Union broke up at the end of the 1980s. Then North Korea lost the bulk of its supply of energy to run its industries. In 1990, for example, it had imported 18.3 million barrels of oil from Russia, China and Iran. Then, abruptly, its imports from Russia fell by 90%, [3] a catastrophic depletion.

Then floods in 1995 and 1996 washed away precious topsoil, damaged and silted dams and flooded coal mining shafts. These natural disasters were followed by a massive drought in 1997, and then by a tsunami. It is difficult to survive twin energy and environmental challenges of this magnitude. The country’s ageing economic infrastructure and systems faltered and fell under the burden. A dangerous feedback loop was created between industrial and ecological decline as the government began burning biomass to create heat and energy to compensate for its meagre supply of oil and gas: ‘North Koreans turned to burning biomass, thus destroying their remaining forests. Deforestation led, in turn, to more flooding and increasing levels of soil erosion. Likewise, soils were depleted as plant matter was burned for heat, rather than being mulched and composted … Biomass harvesting reduces ground cover, disrupts habitats and leads to increasing soil erosion and siltation.’[4]

Since modern agriculture depends upon fossil fuels almost as much as modern industry does, North Korea’s energy crisis was bound to lead eventually to a food crisis. Famine struck the country in the second half of the 1990s. During this period, mass starvation literally decimated the population – about 10 per cent died. This must have been a terrifying time for the nation. Even today, around 6.5 million of the state’s 23 million people are dependent upon food aid from the UN’s World Food Program (WFP). The agency reports that 37 per cent of children and 32 per cent of women in the country are badly malnourished.

So behind the façade of television broadcasts of military pomp and power, North Korea is, in reality, a depleted society unable to properly feed its own population. It is at least half-way along the road to destruction. It has undergone an industrial and agricultural collapse from which it will never fully recover unless it modernises its society and economy. The dilemma for the authorities in Pyongyang is that such a modernisation process would lead rapidly to the demise of its totalitarian political system.

The CIA World Factbook places North Korea 194th in the world according to its GDP – per capita (PPP) of $1,800.[5] It also has a high external debt rate and very weak domestic energy stocks and production. With industrial energy being a driving force of long-term economic growth, the chances are very low of the country undergoing a strong enough economic recovery to buy the time needed to break out of its current political time-warp.

Politically isolated and cut off from modern society and from globalisation, as well as from the world’s considerable knowledge base, North Korea’s economic prospects are, indeed, poor. Veiled in secrecy, the country, tightly controlled by a dictatorship backed by the military, is in chronic lockdown mode.

Looking at North Korea’s current situation I am reminded of how the Maya civilisation declined as a result of a combination of energy shortages, food crises, natural disasters, ecological deterioration and a political vacuum. Inappropriate, rigid leadership, which was unresponsive to the root-causes of its national crisis, played a significant role in the Maya collapse. It is going to be a key element of North Korea’s future fall. The country’s totalitarian military dictatorship, which hosts about 200,000 political prisoners, seems more interested in developing its nuclear weapons programme than in feeding all of its people. The state first allocates fuel to the military and then lets the other sectors – agriculture, transportation and industry – compete for the remainder of the limited fuel supplies available to the country.

Economic progress in today’s highly competitive global world is impossible under such repressive conditions, as China discovered. Pyongyang’s inverted logic shows there is a vacuum of leadership in the country. This is a major factor in collapses of social systems, from the Maya society to modern-day Egypt and Libya during the recent Arab Spring.

Kim Jong Un, portrayed by the Western media as an ‘atomic crackpot’, is incapable of reforming the North Korean state. His brand of totalitarianism relies upon indoctrination and keeping the public ignorant to perpetuate the dynasty’s absurd state personality cult. This, in turn, makes education and information the true enemy of his state. Governance based on public ignorance cannot be sustained indefinitely in an era of globalised internet and mobile communications. The government has been known to mete out severe punishments for citizens using mobile phones or making unauthorised international phone calls.[6] However, as evidence from former communist European states demonstrates, information, from radio, internet and books and magazines smuggled into the country, will invade North Korea. Education will infiltrate North Korea. Freedom will conquer North Korea. This small state cannot hold indefinitely against the forces of global technology revolutionising society across the planet.

Furthermore, when leadership is so globally isolated, it cannot solve global problems like climate change, environmental degradation, famine, disease and, of course, recession and government debt. This produces paralysis in the face of these borderless crises. So often, it is the failure of leadership which allows economic, environmental and social decline to tip over into outright disorder and bankruptcy.

The Mayan civilisation broke down as a result of its over-consumed, exhausted resource base, which increased competition for resources and created internal conflict. Degraded, deforested land such as we see in North Korea, becomes more vulnerable to climate change, which, in turn, further damages the soil and its fertility, leading to worsening droughts and decreased food production. This, in turn, further aggravates competition for resources, leading to social conflict. Social conflict then makes it harder for the kind of collective, co-operative action required to solve the deep-seated socio-ecological dilemma. Decline then slides down into disintegration. From a systems point of view, such destructive feedback loops are difficult to solve even by governments with high competence levels. This kind of collapse is what happened to the Maya. Unfortunately, this is likely to happen to the North Koreans, too.

To understand how this might unfold, it is important to list disaffected groups and ‘voiceless’ citizens who might take part in any Korean Revolution.

- The unemployed and unemployable;

- The poor and hungry masses;

- Workers on farms and in factories dissatisfied with top-down management and lack of labour rights;

- Political prisoners;

- The youth, who are largely in favour of modernisation and modern technology;

- Factions within the echelons of power in Pyongyang;

- Criminal gangs;

- Underground activists and those yearning for freedom and a modern education;

- Thousands of North Korean defectors in China and South Korea itself (it is estimated, for example, that there are about 23,000 North Koreans who have made it via China to South Korea).

Data is not available regarding the numbers of all these groups but it seems reasonable to assume there will be hundreds of thousands of North Koreans, perhaps as many as a million or more, willing to take part in any storming of the Bastille-style political uprising.

It would only take some catalytic force, possibly the next inevitable famine or a leadership power struggle, to release the pent-up, long-repressed anger of these masses and groups.

Which brings me to my concluding question: what effect will North Korea’s collapse have on the rest of the world? Will the regime go quietly or try to take others down with it?

I strongly expect social, economic and environmental problems to escalate in North Korea until the country reaches breaking-point. Either this tipping-point will prompt war against an external enemy, since there’s no stronger unifying force for a failing nation-state than to fight against a foreign threat, or it may prompt some woefully belated economic reform measures from its rulers. As in Russia in the 1980s, when glasnost and perestroika increased, rather than deflated, the revolutionary fervour of the Russian people, such desperate North Korean reforms will only serve to release repressed, large-scale social tensions and the population’s widespread yearning for freedom. At that point, well before 2030, a groundswell of opposition will build, spurred on by the North Korean underground liberation movement and other alienated groups, as well as by the international community. As the state begins to collapse, China, pre-empting the UN and the USA, is likely to intervene from the North, in the guise of a peace-keeping force, to end North Korea’s revolution. A new era will begin of the military occupation of the country as it becomes a colony of the Asian super-power for the following few decades. The upside of this occupation is that it will inaugurate an overdue modernisation process analogous to China’s own economic revival.

At this stage, it seems more probable that North Korea would opt for war as a strategy for holding itself together rather than reform. If a war does, indeed, unfold it would become clear at some point to the generals and soldiers of this tragic nation that they were facing certain defeat. Then a revolution could break out aimed at toppling the country’s government to stop the national suicide.

Despite this bleak outlook for North Korea, there is space, in the long-term perspective, to dream as well. For the likely time-scale for a joyous reunification of a free and democratic Korea is sometime between 2050-2120.

References

CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Washington, D.C. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/kn.html

Diamond, Jared. 2005. Collapse. Allen Lane, Penguin Group, Victoria, Australia, 2005.

Eberstadt, Nicholas. 2016.’Kim Jong Un Is Hell-Bent on a Nuclear War with the U.S.’ – http://europe.newsweek.com/kim-jong-un-hell-bent-nuclear-war-us-497511

Fox News. 2007. ‘150,000 Witness North Korea Execution of Factory Boss Whose Crime Was Making International Phone Calls’. http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,313226,00.html

Haupt, A and Kane, T. 2004. Population Handbook, 5th Edition. Population Reference Bureau. Washington, D.C, 2004.

Pfeiffer, D.A. 2006. Eating Fossil Fuels. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers.

Ryall, J. 2012. ‘North Korea threatens to punish mobile-phone users as ‘war criminals’‘. The Telegraph – http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/northkorea/9040152/North-Korea-threatens-to-punish-mobile-phone-users-as-war-criminals.html

Spodek, J. 2011. Understanding North Korea: Demystifying the World’s Most Misunderstood Country.

Notes

[1] See, for example, an astute and sobering analysis of this situation by Nicholas Eberstadt, entitled ‘Kim Jong Un Is Hell-Bent on a Nuclear War with the U.S.’ – http://europe.newsweek.com/kim-jong-un-hell-bent-nuclear-war-us-497511

[2] At the end of World War 11, North Korea and South Korea were partitioned by the victorious Allies to suit their strategic plans.

[3] Eating Fossil Fuels, by Dale Allen Pfeiffer (New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2006, p.43.

[4] Ibid, p.44, 49.

[5] World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency. Washington, D.C. 20505 https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/kn.html

[6] ‘150,000 Witness North Korea Execution of Factory Boss Whose Crime Was Making International Phone Calls’ November 27, 2007 – FoxNews.com http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,313226,00.html

‘North Korea threatens to punish mobile-phone users as ‘war criminals’‘ – Julian Ryall, Tokyo 26 Jan 2012

Preparing for a Pax Trumpicana

3 August 2016 by Catherine Holdsworth in Codebreaking our future

A blog by Michael Lee, futurist and author of Codebreaking our Future and Knowing our Future.

A Pax Americana is defined as a state of relative international peace overseen by the US superpower. A Pax Trumpicana would be a revision of this order according to a bold, new, highly personalised, US-centric presidency of Donald Trump in the years 2017-2021.

The Upshot election model of the New York Times currently assigns to Hillary Clinton a 75% chance of winning the presidency. NBC News, by contrast, gives Clinton a very slight edge with 46% of the vote to Trump’s 45. I would argue, however, based on an assessment of causal factors most likely to influence the election outcome, that Trump has a 60% chance of becoming the next leader of the Free World. And you don’t need to be a futurist to forecast that the US 2016 election is going to be highly polarising.

In ascribing a probability rating, a futurist would look closely at what’s already known about the subject being predicted. From knowledge of the subject’s properties or characteristics, he/she would make inferences about the likelihood of any given future scenario. All knowledge of the future needs to be based on this logical process of induction, with a clear chain of ideas progressing from what we already know to what we anticipate will come true. A strong prediction will be based on some underlying pattern of behaviour, or structure of reality, which has been observed and which will persist into the time period covered by the forecast. As is always the case with induction, the conclusion can only be justified by the strength of the premises and a sense of the connection between them and the actual prediction. (The methods and principles of building foreknowledge, or foresight, are exhaustively explained in my book on understanding the nature of the future called Knowing our Future. A causal model of the future is then developed in a follow-up book called Codebreaking our Future.)

In this blog, I argue that the macro conditions in America and the world today are more favourable for Trump than they are for Hillary Clinton. In addition, the dynamics of the personal contest between these two presidential candidates also seem to favour a victory for Trump, as will become apparent.

Whether or not you agree with my prediction will depend on your assessment of the strength of my conclusions and the logic which leads to them. The reasons for my conclusions should decisively outweigh the reasons against this case I’m making today. You may also wish to question the relatively high probability rating of 60% for a Trump victory in November. By definition, a statement with a high probability of being true has a correspondingly low chance of being in error. There would be comparatively little doubt about the prediction being right come November 2016.

I’m convinced that the prospect of a Trump victory is markedly higher than it is for a Clinton win. In the end, the candidate who is best aligned to current underlying realities will succeed. In order to help us forecast the outcome of the 2016 US presidential contest, we use knowledge of both candidates, knowledge of the macro conditions which influence voters, both rationally and viscerally, and knowledge of the recent primaries, which culminated in the official nominations by each political party. Statements about the probable future outcome in November need to be based squarely on the total of this knowledge.

It should be mentioned, though, that both the process and the outcome of the presidential election are likely to be something unique in modern times. We haven’t seen an election quite like this before: the first female US presidential candidate competing against an ‘outsider’ thrust into the limelight after an unexpected triumph in the Republican primary elections, all against a background of deep social divisions and tension in America. And the world at large can only be described as turbulent. Pope Francis has even stated recently that it is a world at war, one which has lost its peaceful order.

A world with a high degree of disorder is the right sort of backdrop for a political platform based on ‘law and order’, the perceived antidote to chaos. This is one major reason why I believe the media pundits who give Clinton a 75% chance of victory, or even a slight advantage over Trump, are, like Clinton herself seems to be, out of kilter with important current realities.

But the main reason I think Trump will win in the end is not due so much to the fact that we’re facing a world at war with itself. What’s likely to influence the election outcome most, in my view, comes down to the dynamics of the personal contest between the two leaders. In particular, the billionaire businessman and TV reality star, who is now only one step away from gaining the White House, possesses a preternatural gift for destroying the public persona of his opponents. My sense is that Trump can seriously dent his opponent’s credibility to the point of crippling her ‘brand’ in the zero sum game of a US presidential election.

Let’s take a look at Trump’s rise to national prominence within the last few months to illustrate this point. The Republican Party presidential primaries began in February this year. It’s reported to have been the largest presidential primary field in America’s history, with a total of 17 major candidates. But it quickly turned into something that reminded me of the nursery rhyme about ten green bottles sitting on a wall.

Remember Governor Jeb Bush of Florida, for example? Despite being part of the influential Bush dynasty, Jeb’s comparatively weak efforts ended ignominiously. He was utterly decimated as a candidate. A green bottle that accidentally fell … well, not exactly, that bottle was pushed – by Donald Trump. And then there was retired neurosurgeon Ben Carson of Maryland: great guy, highly articulate, very personable. But knocked out right of the race in no time by Trump’s bullying tactics.

What about the popular Governor Chris Christie, with his high national profile? He’s now been turned into one of Trump’s main attack dogs. Another green bottle. And pioneering businesswoman Carly Fiorina of California? No contest … even though Trump offended the sensibilities of most reasonable Americans by opining that Carly’s facial features disqualified her for the highest office in the land. She’s now a largely forgotten entity. Even charismatic, JFK wannabe, Marco Rubio of Florida lost his ugly media battles with Trump.

And, one-by-one, all the prominent senators, governors and former governors who’d lined up were toppled: Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky, Senator Rick Santorum of Pennsylvania, Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, Governor John Kasich of Ohio, Governor Scott Walker of Wisconsin, former Governor Jim Gilmore of Virginia, former Governor Mike Huckabee of Arkansas, former Governor Bobby Jindal of Louisiana, former Governor George Pataki of New York, and former Governor Rick Perry of Texas.

Senator Ted Cruz of Texas was the only candidate who really gave Trump a run for his money in the whole race to become the 2016 Republican Party presidential nominee. And yet Cruz had to give new meaning to the words stubborn, vengeful, shrewd and tenacious just to stay alive in the game.

After Trump was the last man standing, observers could’ve been forgiven for asking: what happened? Nothing like this has ever been seen before.

What had happened, in fact, was that Trump had reinvented the rules of the game before the contest even began. That’s why, looking back, it appears as if he stage-managed the whole thing in order to control its outcome. His strategy was to shift the focus right out of the traditional political domain and onto social media. That was a game Cruz, who isn’t charisma-intensive, was always going to lose with his prickly public persona. Trump was going to be visceral and he was going to play the game on his terms, winning the social media battle against all his opponents with breathtaking ease.

In fact, not one of Trump’s 16 contenders was equipped to beat him in the new political game of dominating the social space, as opposed to old-style politics.

Trump has two things going for him which gave him the competitive advantage in that space. One, he’s a larger-than-life character, complete with charisma, a free-range hairstyle, an orange spray-on tan and a showy personality. That’s backed up by his ability to project personal strength and positivity. Second, he’s extraordinarily media-savvy. His years on reality show, The Apprentice, gave him more relevant experience in the social media age than all his political rivals from Washington, D.C. put together. He was a ready-made public celebrity right from the start. Fourteen seasons of the show turned him into a household name across the nation. And many of his supporters today come from that very mass television audience. Trump has traded in his reality show signature ‘You’re fired!’ for a political slogan which is resonating with millions of Americans: ‘make America great again’.

But back at the start of the primary season who would have given this controversial and brash New Yorker a chance against all these seasoned contenders? My hunch is that the biggest casualty he’s ever going to fire in his life will be Hillary Clinton. Trump was able to destroy his GOP presidential nominee contenders even when he had absolutely nothing on them, whereas Hillary has given him way too much ammunition. Trump has got four inter-continental ballistic missiles in his armoury for the coming battle:

- Benghazi-gate. On the evening of 11 September, 2012, Islamic militants attacked the American diplomatic compound in Benghazi, Libya, killing the American Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens, as well as U.S. Foreign Service Information Management Officer Sean Smith. Subsequently, the State Department was criticised for turning down prior requests for additional security. As Secretary of State, Clinton had to take responsibility for the security lapses.

- The email server scandal. On 5 July, 2016, the Director of the FBI, James B. Comey, reported back on its investigation into Clinton’s use of a personal email system for some highly confidential communications. The report concluded she and her staff had been extremely careless in their handling of very sensitive, highly classified information. Furthermore, state security could’ve been compromised as the FBI believed that hostile actors may have gained access to the account.

- The rather sleazy sexual legacy of Bill Clinton. The media have made a right meal of Bill’s philandering tendencies for years and, unfortunately, the fall-out from this publicity does reflect negatively, by association, on the prospects of another Clinton being president.

- The idea of a Clinton dynasty is not appealing at a time when the American people are not especially enamoured of that other contemporary dynasty of American politics – the Bush family; Hillary worsened this when she blithely claimed she would put Bill back in charge of the economy if she were chosen as President, forgetting altogether about the rather risky and even unsavoury concept of nepotism.

Each one of these lines of attack would be powerful on their own but their cumulative effect, used cleverly by Trump, could well be to completely undermine the public persona of Hillary Clinton in 2016. Clinton may believe her own mythology but she is going to have to work hard to convince others of it in the face of repeated attacks from Trump.

In short, the trust deficit accrued to Hillary Clinton is massive. With Trump being the undisputed master of the social space at the moment, that deficit may prove terminal in the coming months.

Several macro factors are equally conducive to a Trump triumph.

Firstly, there’s a strong global anti-establishment, anti-globalisation sentiment which is an after-effect of both the 2003 Iraq war, savaged in the recent Chilcot Inquiry, and the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent Great Recession. The self-same anti-establishment sentiments which led to the unexpected election of hard-line socialist Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the British Labour party, the unexpected popularity of left-wing Democrat Bernie Sanders and a UK vote for Brexit, are behind Trump’s surge in populist support. He shows contempt for the conventions of political correctness and millions of his supporters perceive this as a sign of honesty and directness. Hillary, by contrast, is the ultimate establishment elite figure, part of a Clinton dynasty and of a ruling political class which has lost its sheen for swathes of ordinary Americans. Hillary is ‘business as usual’; Trump is bucking the system, riding a populist wave of support. He’s anti-establishment, a rebel with a big cause.

Current events are conspiring against an old-school liberal elitist politician like Clinton in other ways, as I have already intimated. Politically, the world has become radically insecure in 2016. This favours the supposed strength of a law and order candidate like Trump. A refugee attacks passengers on a train in Germany with an axe. This is followed by other attacks in Germany within the space of a week. A young terror suspect and his accomplice murder an old Catholic priest in a quiet suburb in France while he is conducting mass. A man of Franco-Tunisian origin, ploughs a heavy-duty lorry into innocent bystanders in Nice on Bastille Day, killing 84 people, including children and teenagers, and injuring more than 300. A coup breaks out in Turkey, the bridge between Europe and the Middle East, which is then ruthlessly suppressed in an ominous blanket purge. Following a string of police killings of black men during routine arrests, a vigilante sniper in Dallas executes five police officers, and a similar attack takes place in Baton Rouge a few days later, this time leaving three policemen dead.

All this paints a picture for the media consumer of a world in chaos. Conventional politicians like Hillary are looking increasingly out of step with reality. It’s a world of turbulent change in which one should expect the unexpected. At this stage, the stars are definitely aligning for a Trump victory, although it is, of course, possible that some unforeseen event will change the conditions and tilt them back in favour of an established Democrat succeeding Obama. Failing something extraordinary, I see the odds of a Clinton victory inexorably slipping away. Today, from my viewpoint, it’s at least a 60% probability that Trump will be the next US president. That’s because he appears to be on the right side of history at present and has the ability to respond to that climate of opinion in which he can generate serious momentum. Times like these create fear and uncertainty. A candidate who projects strength, and who has a message about his country becoming great again, is more likely to resonate with this fearful public than a business-as-usual candidate. Voting behaviour is both rational and emotional. Millions will vote emotionally for what they see as the path to security, both economic and political.

Charisma on its own, though, may not be enough and the Clinton campaign will put up a huge fight to win the presidency, marshalling all the forces of the Democratic Party machinery. And Hillary herself is immensely intelligent and highly experienced. She will no doubt use the several unscripted and plain weird things Trump sometimes says to portray him as unfit for office. Her other major problem, though, beyond the trust deficit, is her judgment.

Let’s take her choice of an anonymous VP running mate as a recent example of her decision-making. This was a less than inspired choice. Yes, Tim Kaine is genial and universally liked and respected, a safe bet, for sure. But being genial is also a requirement if you want to be chosen to be a shopping mall Santa Claus in the December holidays. Hasn’t Clinton failed once again to read the signs of the times which favour a populist politician like Bernie Sanders? By selecting an innocuous centrist, she has turned her back on the voice of the millions of democrats who fervently supported Sanders. A Clinton/Sanders ticket would have been much more likely to gain the White House than a Hillary/Father Christmas ticket. But Hillary seems to be sticking to her business-as-usual guns.

Now that I’ve given you a flavour of some of the dynamics in the presidential contest and some of the potential causes behind a predicted success for Trump on 8 of November, let’s turn our thinking to what kind of presidency would result should he win. Since it’s going to be unlike any other American presidency, as it will carry a strong personal stamp of the man himself, you’ll need to forgive me for coining a phrase for what a Pax Trumpicana might be like. It’ll be a, well, a pantocracy. A what? you may well be asking.

To explain, I’ll begin with a classic picture of the pantocrator, or ‘ruler over all’:

Now look at this photograph:

Notice the hand gesture?

This is a man who knows how to project authority. Trump used the pantocratic hand signal effectively throughout the primaries as a major part of his body language. Many other pantocrator portraits employ gold to emphasise the sense of power and royalty, as does Trump – check out Trump tower Las Vegas:

The building has a gold sheen – symbolic of wealth, prosperity and power. It’s a contemporary and real symbol of the American Dream which Trump is attempting to reignite in the midst of huge social change. Trump would run the presidency in a profoundly personal way and focus his vision on America, not the world. He will put America first, every time. A Trump presidency would be a pantocracy, that is, a personal form of strong executive rule. It will be the presidency of a personal crusade. It will be colourful, dynamic – quite possibly alarming at times – and characterised by unexpected decisions which will surprise both the conventional left and the traditional right. If Trump puts America first in foreign affairs, and focuses more on domestic, economic issues, this may lead to more latitude for other powers to increase their influence on the world stage. For example, a post-Brexit Britain could forge a stronger role for itself as an independent, influential voice, developing new trade relationships and keeping a balance of power between Europe and the USA.

Those worried that Trump will increase the threat of war may want to consider that he was opposed to the disastrous Iraq war, whereas Hillary Clinton supported the invasion. The huge destabilising impact of the migrant problem today was caused in part by successive ‘regime change’ interventions in the Middle East by the political establishment in the West. It’s not impossible to believe that a post-Brexit Britain could team up with a quasi-isolationist US under Trump to work for greater world peace, while counteracting the IS terror threat which seems to be focused on the European mainland.

The political establishment in recent times has not done a very good job in terms of peace and Pope Francis may be right when he says the world is now effectively at war. This is the net result of years of foreign policy decisions by the political establishment. Perhaps it would not be such a bad thing to try a new approach. A Trump presidency could well offer some fresh perspectives and shape a less unipolar world order, while dealing in a highly focused way with terror.

The pantocratic hand gesture which he loves symbolises the ultimate authority he aspires to. He wants everyone to know he’s decisive. Certainly, his presidency will be decisive – at times decisively wrong, at other times, decisively right. The rest of the world just has to hope that he doesn’t get the big decisions wrong.

The Intelligence Race

9 February 2015 by Catherine Holdsworth in Codebreaking our future

By Michael Lee, author of Codebreaking our Future

One of the occupational hazards of being a futurist is worrying about things long before they happen. One aspect of the future that worries me a lot is how ill-prepared we are for coping with the continued acceleration of the role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the economy.

Just as humans once outstripped animals in the race to dominate Earth, due to our superior brainpower and use of tools, the danger now exists that homo sapiens will fall behind supersmart machines and AI systems in terms of overall efficiency. On top of that, the coming rise of cyborgs, technology-enhanced and AI-enabled humans, could lead to an intelligence divide between them and us which would be even more serious than the digital divide currently prevailing in the field of economic competitiveness.

While the mass media gradually dumb down human culture to about the level of sentience regularly exhibited on the Jerry Springer Show, and while human thought is increasingly fragmented and trivialised by social media like Twitter, celebrity gossip and media-propagated groupthink, and while the once great democratic institution of investigative reporting is reduced to Murdoch-style commercialised and “embedded” journalism, AI is slowly and silently developing much greater capacities which enable its systems and networks to control the main levers of society, from stock market trading to traffic control, from production systems to communication networks. Automation is progressing at the speed of sound, from ATMs and kiosks to drones, from the Google search engine to the Google self-driving car powered by its Google Chauffeur software. In space exploration, automation dominated from the beginning, with Yuri Gagarin becoming the world’s first spaceman thanks to an automated rocket system called Vostok 1 which carried him into orbit.

The truth is, human intelligence is not advancing in today’s post-modern culture, while artificial intelligence is. We need to recognise that there are diverging trajectories of development here. One day, friends, around mid-century, we might wake up in a society controlled almost exclusively by computer programmes, automated systems, IT elites and cyborgs, with humanity, at large, reduced to a pale shadow of itself as a declining subspecies.

Machines and AI systems are already enjoying a spectacular ascent to prominence in today’s economy, taking jobs once carried out by humans. We are entering a phase in which robots and AI systems will take over more sophisticated jobs than those on the assembly-line – receptionists, clerks, teachers, lawyers, medical assistants, legal assistants, pilots, and even so-called “expert systems” like those in the medical profession which can help doctors diagnose diseases like diabetes. In finance, a variety of jobs from loan officers to stockbrokers and traders are being computerised and automated in the coming new world of cyber finance. Finance, it seems, is increasingly reliant on AI and incredibly fast and powerful computers, based on algorithms which can analyse and execute trading deals according to mathematical models.

Clearly, what computer programmes and systems can do is now moving inexorably up a chain of sophistication and complexity. Eventually, one imagines, what can be automated, probably will be – due to the relentless competitive pressures for efficiency and efficacy which prevail in society. Research done by Oxford University predicts that 47% of the human workforce could face replacement by computers.

Let’s briefly revisit what we mean by the terms Artificial Intelligence, the digital divide and, now, the Intelligence Divide.

Apparently, Artificial Intelligence, a branch of computer science which investigates what human capacities can be replicated and performed by computer systems, was a phrase coined in 1956 by John McCarthy at MIT. This field includes such aspects as programming computers to play games against human opponents [1], robotics, developing “expert systems” and programming computers for real-time decision-making and diagnosis, understanding and translating human languages (the ability for artificial “talk” or speech), and the area of simulating neural processes in animals and humans to map and imitate how the brain works.

This is one of my favourite definitions of AI: “The study of the modelling of human mental functions by computer programs.” [2]

The digital divide refers to the gap between those who have access to Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs), especially the Internet, and those who don’t. In effect, the digital “have-nots” are those billions living in poor and deprived social conditions who don’t have the education and skills to know what to do with digital technology and internet even if they did have access to them.

The Global Information Technology Report 2012: Living in a Hyperconnected World [3], published by the World Economic Forum, found that the BRICS countries, led by China, still lag significantly behind the ICT-driven economic competitiveness.

In 2014, The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), looked into the role of education in cementing the global digital divide. The organisation concluded that in many countries, large parts of the adult population have non-existent or insufficient ICT problem-solving skills. For example, they reported, “Between 30% and 50% of the adult population in Ireland, Poland and the Slovak Republic fall into this category.” [4] Yet, as advancing societies become more knowledge-intensive, a growing number of jobs require at least basic ICT skills.

But the digital divide in the world, based on both access to ICT and the education skills to know how to use it, is only the precursor of an Intelligence Divide (ID) which, ultimately, could become an even deeper social fracture than racism has been in the world. The Intelligence Divide would be the growing gap between what human intelligence can do without computer power compared to what AI systems, computer programs and AI-enabled humans, including cyborgs, achieve across a range of intelligent activities including thinking, calculating, decision-making, perceiving, communicating and organising. The divide would be measured in terms of ratios of efficiency and effectiveness for the same activity performed respectively by humans and AI systems and cyborgs in any given social context.

Whether or not a deep Intelligence Divide develops, an Intelligence Race is already underway on the economic front between humans and AI. This race is not about whether a computer can beat a human chess champion but about which jobs can be done better, and more efficiently, by machines than by humans. More and more processes can be automated and this will likely mean fewer jobs for humans in the long-run. The Intelligence Race is sure to become a defining trend of this century.

What concerns me is that our post-modernist world, dominated by the trivialisation of the mass media, the corruption of democracy and the globalisation of self-serving commercialisation, is catapulting humanity into intellectual decline at a time when AI is on the rise. This is one of the main reasons why I’ve become a neo-progressionist. Why let Artificial Intelligence progress at our expense instead of boosting all forms of progress in a wiser, more holistic approach?

The 6,000 year journey of civilisation is still in its infancy when measured in time-scales of the cosmos and the biosphere itself and this probably means humanity has nowhere near reached its full potential. Of course, I would much prefer to see human intelligence increasing, not declining, before it’s too late to stop the Intelligence Divide from taking root in the evolution of our history.

See Michael Lee’s video on YouTube “Finding Future X” at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XQItLRhzkMY

[1] In May, 1997, the super-computer called Deep Blue defeated world chess champion Gary Kasparov in a chess match.

[2] Collins English Dictionary:85. (Harper Collins Publishers, 4th edition, 1998). Some other definitions of AI include:

“A term applied to the study and use of computers that can simulate some of the characteristics normally ascribed to human intelligence, such as learning, deduction, intuition, and self-correction. The subject encompasses many branches of computer science, including cybernetics, knowledge-based systems, natural language processing, pattern recognition, and robotics.” The Cambridge Encyclopedia 4th Edition.(CambridgeUniversity Press, 2000.) “The theory and development of computer systems able to perform tasks normally requiring human intelligence, such as visual perception, speech recognition, decision-making, and translation between languages.” The New Oxford Dictionary of English. (Oxford University Press,1998. )

[4] “Trends shaping Education 2014 Spotlight 5” by the OECD www.oecd.org/edu/ceri/trendsshapingeducation2013.htm

Codebreaking our future

23 December 2014 by Catherine Holdsworth in Book publishing, Codebreaking our future

Michael Lee’s new video, ‘Finding Future X in Cape Town,’ discusses his book, Codebreaking out future and the impacts of time and casuality on the future. Perhaps your 2015 resolution will be to break the code of the future…

Watch the video here

Competition: Best International Prediction of 2014

4 August 2014 by Rebecca in Codebreaking our future

To celebrate the release of Codebreaking our Future by Michael Lee we are offering readers of our blog the chance to win a free subscription to the FutureFinder System for Individuals, which will help you identify future influences you can monitor.

While we’re interested in all your theories about the future, however outlandish, this article might help you come up with more reliable predictions. Once you’ve looked at these successful predictions (from Knowing our Future) and the methods behind them, let us know, in 300 words or fewer, using the form below, what your prediction is and how you arrived at your conclusion.

Michael Lee offers the following additional advice for predicting our future:

- Read the news and pick an area of interest in which you would like to make a forecast (for example, technology or politics);

- Look into the history of the evolution of the entity or subject you’ve chosen, to the current time;

- Try to identify causes or strong influencing factors most likely to affect outcomes in this field;

- Make your own rating of probabilities of possible outcomes based on this causal analysis, and choose pathways and outcomes which have strong probabilities.

Closing date is 5 September 2014. The winner will be notified by 19 September and their idea published on this blog and on the Institute of Futurology site. The subscription to the FutureFinder System for Individuals will be shared with the winner who will then be able to use the system without charge.

We're sorry but this competition has now closed.

The Depopulation Time Bomb

28 July 2014 by Infinite Ideas in Business and finance, Codebreaking our future

by Michael Lee, author of Codebreaking our future

The future of nations is not written in the stars but in their demographics. In particular, a futurist can study national fertility rates, urbanisation trends and the age structure of population groups to get a picture of a country’s long-term future.

Remarkable polymath Benjamin Franklin was one of the founding fathers of America and, back in the 1770s, he enjoyed unbridled optimism about the future of his nation, which at the time was still overwhelmingly rural and comparatively “backward”. Why, then, was his prognosis so rosy? America’s birth-rate, he reasoned, was double that of Europe’s. Today, the position in America has been reversed and there are no grounds for any of Franklin’s demographic optimism. Between 1990-2002, the crude birth rate in the US declined by 17%. Similar declines are happening right across the developed and developing world. Before discussing this in more detail, let’s paint in broad brushstrokes the background for understanding the world’s current demographics.

The stand-out feature of a general picture of population trends is the astonishing discrepancy between underlying demographics and the current distribution of global power and wealth. It’s this disconnect which highlights the spaces in which the international order is going to shift in the coming decades. One can map international influence against population profiles to highlight this incongruity.

|

Region |

Total population (in millions) |

Annual rate of increase of population (%) 2010-2015 |

|

Asia (including Middle East) |

4,254,524 |

1.0 |

|

Africa |

1,083,524 |

2.5 |

|

Europe |

741,971 |

0.1 |

|

Latin America & the Caribbean |

609,807 |

1.1 |

|

North America |

352,471 |

0.8 |

|

Oceania (Australia, NZ, Polynesia, etc) |

37,775 |

1.4 |

|

World |

7,080,072 |

1.1 |

Table 1: World Population at 2012

(Sources: UN Demographic Yearbook 2012;

UN Population & Vital Statistics Report Series A, Vol. LXVI)

Observe in Table 1 that only Africa’s rate of population increase is significantly higher than the rather meagre global average of 1.1% per annum. Populations outside Africa and parts of Asia are just not increasing with any kind of vigour. You will also note that Africa and Asia (including the Middle East) together make up just over 75% of the world’s population at 5,338,048. By contrast, Europe makes up 10.5% of the world, Latin America & the Caribbean 9%, North America 5% and Oceania 0.5%. But something is interesting here. There is a complete mismatch between these population sizes and the distribution of global geo-political power today.

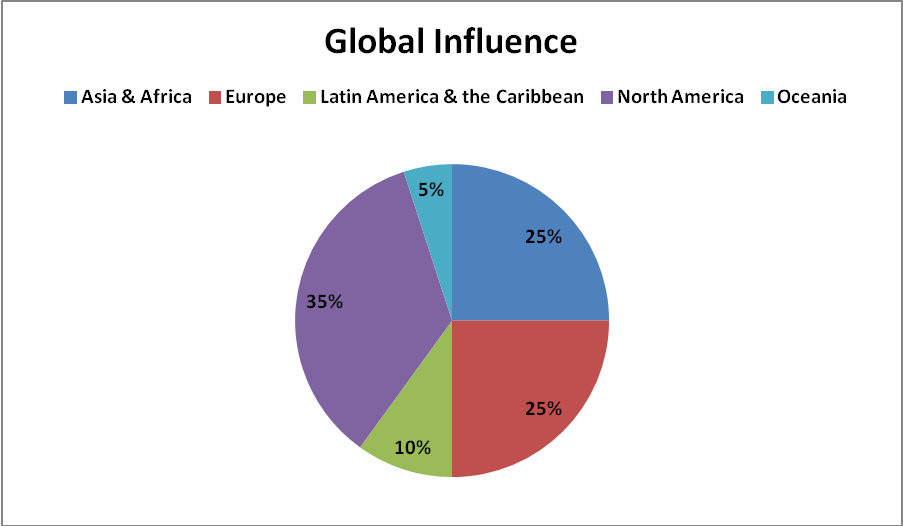

For example, if one estimates global economic and political influence by regions, it might well look something like this:

Figure 1: Estimated Global Influence by Region (Source: author)

In Figure 1, the dominant powers are North America and Europe, with 35% and 25% of global influence respectively. Next comes Africa and Asia together providing approximately 25% of the influence, Latin America & the Caribbean a further 10% and Oceania fighting above its demographic weight division at 5%.

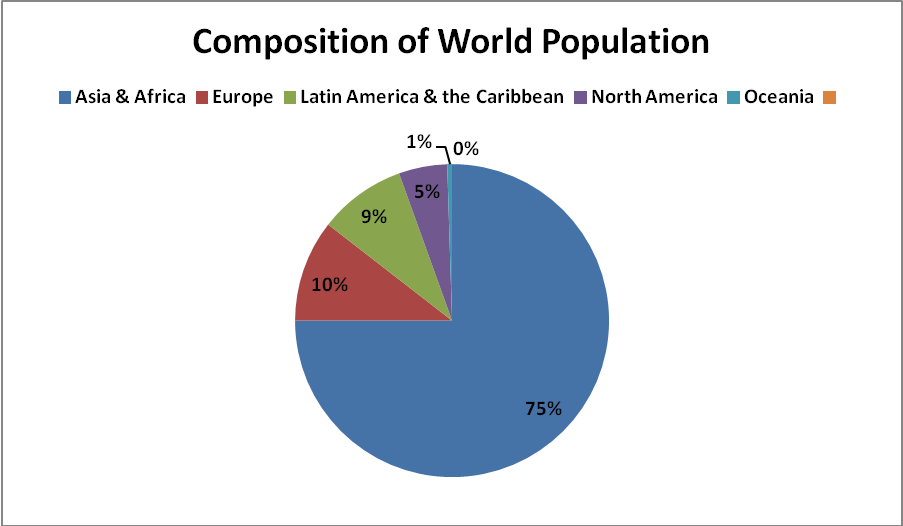

Now, let’s turn to underlying population sizes for a completely different picture.

Figure 2: Composition of World Population by Region (Source: author)

North America, with 35% of the influence, has 5% of the global population. Europe, with 25% of the influence, has 10.5% of the population. Africa and Asia, with only 25% of the influence, have 75% of the population. Latin America & the Caribbean have 10% of the influence and 9% of the population. And Oceania has 5% of the influence but only 0.5% of the population. This skewed distribution of power is bound to change on a large scale throughout this century.

Population sizes indicate the potential magnitude of an economy and its markets, in the sense that its citizens are the producers, the consumers and the tax payers. Of course, urbanisation and development levels have to be factored in, too, as do resources. In addition, the age structure of the population, whether it is young and growing or ageing and declining, is a key consideration. Crudely, though, the following mapping of global influence over population size provides a context for speculation on future shifts of influence, highlighting from which regions they are most likely to come.

|

|

Relative Influence |

Relative Size |

Probable long-term shift in influence |

| Asia and Africa |

25% |

75% |

Greater |

| Europe |

25% |

10.5% |

Lower |

| Latin America & the Caribbean |

10% |

9% |

Equal to |

| North America |

35% |

5% |

Lower |

| Oceania |

5% |

0.5% |

Lower |

Table 2: Relative influence versus size to indicate potential shifts of influence (Source: author)

Table 2 is only a rough guide to potential future shifts of international influence based on the simple equation that size matters when it comes to economies, especially, as mentioned, when seen in the context of developmental factors and the age profile of the population in question. (You are welcome to play around with the figures for estimated global influence by region to come up with your own “map”). The differentials between influence and size in Table 2 are:

Africa & Asia = 50% +

Europe = -14.5%

Latin America & the Caribbean = -1%

North America = -30%

Oceania = -5.5%

These differentials show the conditions for extensive changes of power in the coming decades. It’s an X-ray of a future changing international order.

The population sizes for the countries in the BRICS trade bloc of developing economies, for example, are:

Brazil: 190.7 million

Russia: 143.4 million

India: 1.2 billion

China: 1.3 billion

South Africa: 51 million

If one takes the “CIA” regions of the world – China/India/Africa – the population sizes are:

China: 1.3 billion

India: 1.2 billion

Africa: 1 billion

= 3.5 billion (about 50% of world’s population)

The size of potential new and extended markets in these CIA regions is vast and there is likely going to be an increasing wealth base and growing influence across these regions.

I regard demographics as one of the most impressive of all the social sciences. This discipline largely deals with real, socially significant population data. Its figures are squarely based on facts. This allows for robust, evidence-based reasoning. With demographics, we’re looking into a radar of the future.

Which brings me to a disturbing reality I wish to share with you today. Like the inferences made from the data in Table 2, this fact may appear, at first glance, to be counter-intuitive. I referred earlier in looking at Table 1 to the meagre global rates of annual population increases this century. Birth-rates are falling all over the world in deeply entrenched trends rooted in the very nature of modern society. A human depopulation time bomb is ticking.

Human population growth is decreasing at a rate which will imperil the global economy, destabilise some societies and ultimately threaten humanity’s prospects for survival.

US demographer and senior fellow at the New America Foundation, Phillip Longman, explains: “World population growth has already slowed dramatically over the last generation and is headed on course for absolute decline. Indeed, forecasts by the United Nations and others show the world population growth rate could well turn negative during the lifetimes of people now in their 40sand 50s.”[1]

Longman is warning us that population growth for humanity is likely to turn negative around mid-century. This means the world’s total population size would start to decrease in absolute terms. If such a trend ever became irreversible, it would eventually lead to the extinction of the human race.

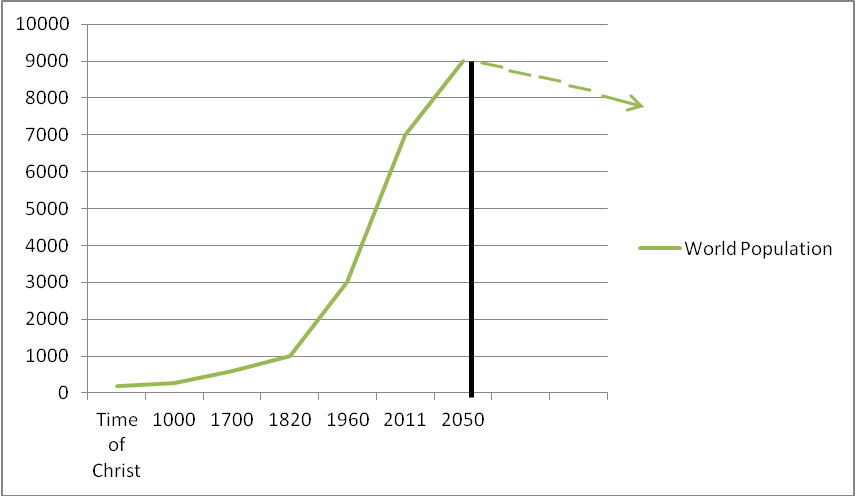

Figure 3: The rise of world population to its projected peak in 2050

Figure 3 indicates that the total human population may peak in 2050 at nine billion and thereafter decline year after year, decade after decade, generation after generation. It’s not a comforting thought that Population Peak for the human race is probably just up ahead of us.

Shrinking nations and families conjure up nightmarish scenarios of a declining world population. If sub-replacement fertility rates across the world continue compounding century after century, it’s a mathematical certainty that the human race will one day become extinct.

The core fact is that global fertility rates are half what they were in 1972. This is disconcerting given that fertility rates are what keep the human race reproducing itself. The fall in global fertility is the key global problem to address in this century.

The following data together brings home the extent of this trend, bearing in mind that the replacement fertility rate is 2.1 children per women and that, at the start of the 20th century, the global fertility rate was higher than five children per woman of child-bearing age:

- The world’s population growth rate has fallen from 2% p.a. in the late 1960s to just over 1% today, and is predicted to slow further to 0.7% by 2030 and then 0.4% by 2050.[2]

- 62 countries, making up almost half the world’s population, now have fertility rates at, or below, the replacement rate of 2.1, including most of the industrial world and Asian powers like China, Taiwan and South Korea.[3]

- Most European countries are on a path to population ageing and absolute population decline[4], in fact, no country in Europe is demographically replacing its population[5] – “If Europe’s current fertility rate of around 1.5 births per woman persists until 2020, this will result in 88 million fewer Europeans by the end of the century.”[6]

- Spain has the lowest fertility rates ever recorded

- Russia, and most of the Balkans and Eastern Europe, are facing a fall in the size of their populations of between 13-35 % in the next four decades, with China’s starting to fall between 2030- 2035 and Thailand’s after about 2040[7]

- Japan’s fertility rate is 1.4 children per women, one of the lowest

- China’s fertility rate is between 1.5 and 1.65

- Cuba has one of the lowest fertility rates in the world

- Italy, once the seat of the Roman Empire that ruled most of the known world, has a disastrously low fertility rate of 1.2

- Since 1975, Brazil’s fertility rate has dropped nearly in half to just 2.27 children per woman[8]

- By mid-century, China could lose 20-30% of its population every generation[9]

- By 2050, the median age of the world’s population will be 38 years, in Europe, 47, China, 45, in North America and Asia about 41[10]

It’s the scale of the depopulation problem that is daunting. Longman explains: “All told, some 59 countries, comprising roughly 44 percent of the world’s total population, are currently not producing enough children to avoid population decline, and the phenomenon continues to spread. By 2050, according to the latest United Nations projections, 75 percent of all countries, even in underdeveloped regions, will be reproducing at below-replacement levels.”[11] Consequently, he’s expecting the world population to peak around 2050.[12]

A silent demographic revolution is happening to our world.

Associated with human depopulation is the inevitable ageing of the global population. [13] This will have dramatic, long-term impacts on economies. Population trends drive changes across a range of fields from economics and finances to politics, from sociology to international relations. Ageing populations spend less and produce less, depressing business demand. Societies in Asia, Europe and the Americas are turning grey and there are concerns about the drain on public expenditure and the loss of national productivity which will ensue. Population ageing will place added burdens on both government finances and the working generation. This affects the economy directly: “There is a reasonably robust theory…that suggests people accumulate wealth between the ages of 30 and 60 for retirement, after which they tend to save less or ‘dis-save’.”[14]

Longman establishes a link between demography and economics early in his landmark book The Empty Cradle: “Capitalism has never flourished except when accompanied by population growth.”[15] Businesses, he says, go where populations are growing, not where they’re declining. Why? Because there’ll be more demand for their goods: “More people create more demand for the products capitalists sell, and more supply of the labor capitalists buy.”[16] Here’s the simple equation illustrating the loop between demographics and economics: “Because of today’s low birth-rates, there will be fewer workers available in the future to produce the goods and services consumed by each retiree.”[17]

And here’s the result for the economy: “The working population of the United States essentially will wind up paying one out of every five dollars it earns just to support retirees, while simultaneously trying to finance more and more years of higher education…”, creating financial disincentives for families to produce many children.[18]

A stagnant population, in other words, is likely to produce a stagnant economy. When there’s depopulation, investment and business confidence eventually vanish, along with economic growth: “Without population growth providing an ever increasing supply of workers and consumers, economic growth would depend entirely on pushing more people into the work force and getting more out of them each day.”[19]

In sum, then, there are significant declines in birth-rates right across the world, sometimes well below replacement levels. The depopulation time bomb isn’t science fiction, it’s a matter of demographic fact.

The populations of major nations like Japan and Russia are already shrinking in size at worrying rates.

Japan, once the 2nd largest economy in the world, is now into its third decade of sluggish growth due to its twin curses of declining population and productivity and population ageing. In desperation, it’s turning to robotics to inject new life into its zombie economy.

Similarly, Russia is facing its own depopulation bomb. It’s estimated to lose between 13-35% of its population size in the next four decades. In 1937, Russia had a population of 162 million. This has fallen to 142 million. It’s predicted to fall further to about 80-90 million by mid-century. Between 1937-2050, then, the country’s population size could have halved. At a time when it’s once again emerging as an energy giant, its demographics, ironically, are undermining its future prospects. The demographic challenge of halting depopulation will be complicated by the presence of an estimated 14.5 million Muslims in the country which may threaten unity and heighten ethnic tensions within its borders.

As a futurist, I have to admit my blood runs cold when I consider such overwhelming and conclusive evidence of humanity losing its appetite to reproduce itself.

Acknowledgments

Longman, P. 2004. The Empty Cradle. New York: Basic Books.

Magnus,G. 2009. The Age of Ageing. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons..

“Population and Vital Statistics Report, Series A Vol. LXVI”, Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Department of Economic an d Social Affairs Statistics Division. See http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/default.htm

UN Demographic yearbook 2012 (63rd Issue), New York: 2013.

[1] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004)7.

[2] Magnus, The Age of Ageing (2009) 33.

[3] Magnus, The Age of Ageing (2009) 40.

[4] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 61.

[5] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 177.

[6] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 67.

[7] Magnus, The Age of Ageing (2009) 158.

[8] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 32.

[9] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 11.

[10] Magnus, The Age of Ageing (2009) xxi-xxii.

[11] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 26.

[12] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 27.

[13] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) xiii.

[14] Magnus, The Age of Ageing (2009) 114.

[15] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 4.

[16] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 4.

[17] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 19.

[18] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 22.

[19] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 5. Longman states: “A nation’s gross domestic product is literally the sum of its labour force times the average output per worker. Thus, a decline in the number of workers implies a decline in an economy’s growth potential…The European Commission…projects that Europe’s potential growth rate over the next fifty years will fall by 40 percent due to the shrinking size of the European work force.” Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004).41. He further elaborates as follows: “Exploding health and pension costs, along with a shrinking tax base, diminish resources available to households, government, and the private sector for investing in the next generation, even as the need for human capital formation increases. Another reason is rooted in the realities of the life cycle. It’s not just that most technological breakthroughs and entrepreneurial activity tend to come from people in their 20s and 30s…an ageing population will likely become increasingly risk averse….” Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 43.