Business and finance

Top 10 management models for your business: #1 The bottom of the pyramid

5 June 2014 by Infinite Ideas in 100+ Management Models, Business and finance

by Fons Trompenaars and Piet Hein Coebergh, co-authors of 100+ Management Models.

How can one create wealth by doing business with the 4 billion people at the bottom of the financial pyramid?

Essence

In economics, the bottom of the pyramid (BoP) is the largest, but poorest socio-economic group, comprising around 4 billion people who live on less than US$2.50 per day. Conventional logic holds that there is little business to be done with this ‘market segment’. Together with academics Stuart Hart and Allen Hammond, C.K. Prahalad turns this logic around by analyzing how the total buying power of this group could be stimulated, as long as there is access to vital resources such as money, telecommunications and energy.

The simple observation is that because there is much untapped purchasing power at the bottom of the pyramid, private companies can make significant profits by selling to the poor. Simultaneously, by selling to the poor, private companies can bring prosperity to the poor, and thus can help eradicate poverty. Prahalad suggests that large multinational companies (MNCs) should play the leading role in this process, and find both glory and fortune at the bottom of the pyramid. Prahalad suggests that there is much eagerness to do business in this sector – as long as traditional barriers can be modified.

How to use the model

To enable poor people to use their buying power, Prahalad suggests making use of the following twelve building blocks. Solutions must:

- be low priced

- merge old and new technology

- be scalable and transportable across countries, cultures and languages

- be eco-friendly

- put functionality above form

- be based on innovative processes

- use deskilled work

- educate customers

- work in hostile environments

- be flexible with interfaces

- be available for the highly dispersed rural market as well as highly dense urban markets

- be fit for rapid evolution

Results

The idea behind BoP has enjoyed global acceptance since its presentation in 2002. An earlier example of how doing business with the poor can pay off for all stakeholders is given by the success story of Bangladeshi banker, economist and Nobel Peace Prize recipient Muhammad Yunus, who developed the concepts of microcredit and microfinance, small loans given to entrepreneurs too poor to qualify for traditional bank loans. Other examples include the limited success of the Tata Nano car and the success of Hindustan Lever Ltd., one of Unilever’s largest subsidiaries.

Comments

Critics have claimed that the BoP proposition might be too good to be true. Karnani (2006) states that the BoP proposition ‘is, at best, a harmless illusion and potentially a dangerous delusion. The BoP argument is riddled with inaccuracies and fallacies.’ Other than the success of microcredit, there have not been many convincing examples of the fortune to be made at the bottom of the pyramid (Kay and Lewenstein, Harvard Business Review, April 2013).

Literature

Karnani, Aneel G. (2006) ‘Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: A Mirage’, Ross School of Business Paper No. 1035, Available at Social Science Research Network.

London, T., Hart, S.L. (2011)Next Generation Business Strategies for the Base of the Pyramid: New Approaches for Building Mutual Values, Upper Saddle River, Pearson.

Prahalad, C.K. (2004) Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty through Profits. Philadelphia, Wharton School Publishing.

Understanding business finance

4 June 2014 by Catherine Holdsworth in Business and finance

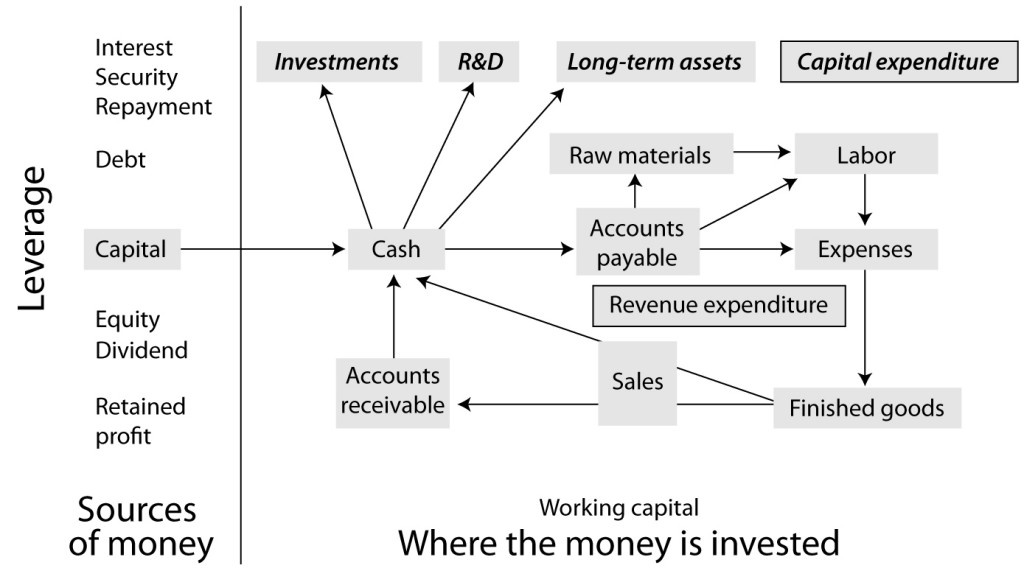

To understand business finance it is useful to have a diagram of how money flows round a business. Here is the business model:

Today we’re going to look at sources of money

The money used (or capital) in the business comes from stockholders (the owners) and lenders. Initially, the owners will pay for shares of stock and this money is invested in the business. As profits are earned, some of these profits are returned to the stockholders by way of dividends. If a company wishes to grow, it will retain profits within the business. These retained profits still belong to the stockholders but are being used to finance growth.

In the past, the term ‘stockholders’ funds’ was used to describe the amount of stockholders’ money invested in the business. The modern term is ‘equity’. Equity is therefore made up of the stockholders’ initial investment plus retained profits. The company owes this money to the stockholders but has no obligation to pay it back.

A company can borrow cash from a variety of sources. In a small business, the owners will often provide loans to the company – sometimes at a low rate of interest. The line of credit from the company’s bank is a popular form of financing since the company can access cash according to the needs of the business. However, lines of credit will usually carry a higher rate of interest than a long-term loan.

There is a wide range of other financial institutions seeking to lend to businesses. For the purposes of this book about basic finance, we will consider only the straightforward case where the loan is for a fixed term.

The implications of these two sources of money are different. In one sense, money from stockholders is cheaper. Return on the stockholders’ investment comes in the shape of dividends that are normally paid twice a year. In the early stages of a business the owners may very well drop the requirement for dividends and allow the managers to retain all the profits to allow them to grow the business. At that stage the money could be said to be free.

There is also no need for the managers to plan to have the cash to buy back the stock; in practical terms the money is in the company forever. The only downside in using stockholders’ funds to get a major business going is the cost of raising money in this way, since lawyers and accountants don’t come cheap. Another problem is that the business has to find someone willing to take the risk of putting money into an enterprise which, who knows, may fail. If the business does fail the owners lose all the money they have invested. It is this risk of failure which makes stockholders demand, in the long term, that their overall returns should be higher than the providers of loans. They get this return through the growth of dividends that the company pays out. In the long term, of course, if the company’s stock is traded on a stock market exchange the stockholders are hoping that the price of the shares will go up.

Loan finance (usually referred to as debt) is cheaper to arrange. Banks and financial institutions assess the risk of the company, make loans and charge an interest rate to reflect the perceived risk. It seems reasonable that they should tailor their interest charges to protect themselves against the risk of default; the problem is that a business in dire straits and in desperate need of cash has to pay more to get it – adding to the downward spiral.

Also, with debt, don’t forget, you have to plan how you’re going to repay the money within the agreed timescale.

Leverage

Leverage is a term that accountants use to confuse people. It is used in a variety of situations but always has the same implication. The easiest way to explain leverage is to describe a familiar situation. Suppose I buy a house for $100,000 with a 90% interest-only mortgage. I have put in $10,000 of my own money and that is my ‘equity’ in the house. Consider what happens if the value of the property goes up by 10%.

| Original position | New position | |

| Value of house | $100,000 | $110,000 |

| Mortgage | $90,000 | $90,000 |

| Equity | $10,000 | $20,000 |

The value of the property has gone up by 10% but my equity has gone up 100%. Excellent: easy money! The risk, of course, is that the price of the property may fall by 10%, in which case all of my equity is wiped out. If the value falls further, then I am into the position known as negative equity – note how financial terms are often used in everyday life.

The effect of leverage is to multiply my gains. In this case a 10% increase in the value of the house gave me a 100% increase in equity. Leverage is 10x (ten times). Notice that this multiplier can be applied to any percentage change in the value of the house. So, for example, a 25% increase in the value of the house in our example will give a 250% increase in equity.

In the next blog we’ll look at where the money is invested.

Everybody’s talking about … Leverage

30 May 2014 by Rebecca in Business and finance

For many defenders of the English language this poor, unsuspecting word is the grandfather of nouns converted into verbs for the convenience of business. But should we allow it to continue to be pimped out to the dim and lazy or at least try to rehabilitate it as a noun?

Where did it come from?

It was Archimedes who said, ‘Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.’ Archimedes was an ancient Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer and inventor credited with the explanation of the lever and the invention of a screw pump still used today – the Archimedes screw.

Clearly, he was a smart guy and he’d probably be spinning in his grave like a ceiling fan if he knew his wise observation had been corrupted by mediocre business executives intent on looking more competent than they really are.

When it made its way into business speak is unknown, and who we should blame for it is equally obscure.

But what does it mean?

Leverage is used to imply an assisted or additional advantage. In the same way that Archimedes could move something immovable with the help of a strategically positioned lever, business believes it can move profit upward by a strategically positioned ‘leveraged’ advantage. Or at least the executives in question believe a rousing speech on leveraging assets might help.

In many ways it’s a tautology like ‘added bonus’ or ‘free gift’. A bonus is by definition added or extra so the addition of added is meaningless. A gift is by definition free so the addition of free is unnecessary. Using leverage to explain the exploitation of a strategic or tactical advantage in business is also meaningless and unnecessary because by definition that’s what business is supposed to be doing in the first place. If a business has a nifty IT system, a patented design or particularly smart engineers surely it would be plain stupid not to take advantage of those things.

In many ways it’s a tautology like ‘added bonus’ or ‘free gift’. A bonus is by definition added or extra so the addition of added is meaningless. A gift is by definition free so the addition of free is unnecessary. Using leverage to explain the exploitation of a strategic or tactical advantage in business is also meaningless and unnecessary because by definition that’s what business is supposed to be doing in the first place. If a business has a nifty IT system, a patented design or particularly smart engineers surely it would be plain stupid not to take advantage of those things.

That said, leverage is also used as a specific finance term for any technique to multiply gains. Also known as gearing, it usually involves borrowing money to buy additional assets in the hope those assets will yield more profit than the cost of borrowing the money. Obviously this doesn’t always pan out so the losses rather than gains are often multiplied.

This dichotomy of meaning leads to the utterly ridiculous possibility of leveraging the leverage!

Where will I find leverage used?

This particular gem of business jargon is extremely versatile and can be found in meetings, reports and presentations across business, from finance (where it may actually be a meaningful term) to marketing, strategy and even shareholder meetings. It needs to be stamped out.

For example, when a CEO addresses a shareholder meeting and expresses his intention to, ‘leverage our significant investment in IT infrastructure across all the business units to drive profits and increase market share’, rather than nodding enthusiastically at this gibberish the shareholders should throw a few eggs and respond, ‘well I should hope so, otherwise why make the significant investment in the first place!’

How can I leverage my advantage?

The ‘beauty’ of the word leverage and the reason it is so popular in business is that it sounds good but means very little. It can be used to replace just about any activity verb. And, like so much of the worst business jargon it’s passive. It’s therefore easy to see why it’s wheeled out so often.

So if you have a report to write but you’ve not really done what you were supposed to do by the time you were supposed to have done it then ‘leverage’ is a fantastic little word that can get you off the hook. If you are ‘leveraging a project’, the reader has no way of knowing whether you’ve barely started it, almost finished it or palmed it off to someone else who is ignoring it! It’s particularly useful for speculative documents such as business plans and project proposals because it’s so vague. Plus it’s almost always accompanied by the unspecified ‘we’ not the specified ‘I’, thus enabling its user to abdicate all responsibility or accountability for the actual leveraging.

As a result of these special obfuscatory qualities the word leverage is incredibly useful for corporate minions eager to look good but do as little as humanly possible. It allows for non specific, passive inference of action occurring without saying what that action is, who is taking that action or when said action will be completed, and therefore implied value realised. In practical terms it allows subordinates to report on progress while still allowing the realities of a project to actually run the project. So much so that if you see a report, update or article that contains the word leverage you can pretty much guarantee that nothing is happening or that whatever is happening is happening a great deal slower than anyone could have thought possible.

Unless you are specifically talking about financial leverage or borrowing money to capitalise on an opportunity that could increase value then avoid the term. At the very least ‘leverage’ should remain a noun (as in ‘to apply leverage’) and not be pimped out as a passive pseudo-verb (as in ‘we are leveraging our infrastructure’). And whatever you do don’t do what one company did in 2001 when it made people redundant and told them the business was ‘leveraging their synergies’.

Everybody’s talking about … User Experience (UX)

23 May 2014 by Rebecca in Business and finance

There are some business phrases that seem to burst on the scene from nowhere and get used by everyone. It’s still unclear whether UX will find a permanent place in business vernacular or sink without a trace.

Where did it come from?

Donald Norman, an academic in the field of cognitive science, design and usability is thought to have coined the term in the mid 1990s, although his definition of the user experience was not the same as the definition commonly used today. These days it’s bandied about in just about every industry although its origins were firmly planted in technology and manufacturing.

But what does it mean?

So what is it? Basically it’s how someone feels about using a product or service. In days gone by our appreciation of a product or service was largely limited to the functionality of the product. Did it work? Did it break down a lot? When things went wrong was a company representative available to help put things right? Did it look good?

Today the user experience still incorporates issues of functionality and performance but includes a holistic (oops, sorry – there’s another word that’s been hijacked by the business world) perspective on how a person feels about using the product or service. The focus has therefore moved past whether or not the thing is fit for purpose and is increasingly focused on pleasure, enjoyment and value as well as performance.

Where will I find UX used?

User experience can be found in every nook and cranny of business – from the service sector to manufacturing. On one hand it’s really another example of business trying to look über-smart by stating the obvious. Most people want to like the products they buy, they want to enjoy using them and they want them to add genuine value to their lives, and common sense alone confirms that this interpretation is not just down to functionality. On the other hand it is quite useful – especially around product design.

Think for a moment about Heinz tomato ketchup. Whether you agree with the sentiment that there really is only one tomato sauce or not it’s a useful analogy for making the distinction between designing the product and designing the experience. The product designer created the old fashioned glass bottles that required a lot of ‘bottom slapping’ or a fair amount of wiggling about with a knife to get any sauce out the bottle – especially as it began to run low. The user experience designer on the other hand was the person who designed the flip top, anti-drip squeeze bottle that sits on its lid and provides a continuous, mess-free supply of sauce for your burgers.

It’s a focus on user experience that creates smart, useful innovations that make you think, ‘Wow why did it take so long for anything to think of that!’

What’s the UX for my company?

What’s the UX for my company?

Any business that is committed to keeping its customers happy and loyal needs to consider the user experience and its ability to deliver value and a user experience that is appreciated by those customers.

In relation to your products or services do you even know what your customers value the most? There are five main aspects of usability that affect whether or not your user has an enjoyable, ‘relationship enhancing’ experience with your product or whether they want to smash it to smithereens with a hammer!

When considering your product or service ask yourself:

- How easy is it to learn and use? Generally speaking the quicker the user can learn how to use the product the better the user experience.

- How efficient is it? Does the product or service deliver what it was designed to deliver with minimal effort on the part of the user?

- How memorable is it? If the user doesn’t use your product or service for a while, how easy is it to remember how?

- How effective is it? Is the product or service error free? Or if an error occurs are they quickly rectifiable?

- How satisfied are users with your product or service? Do they like using it or is it a chore? Design faults that may seem minimal can quickly become a source of frustration and irritation that can decimate user experience.

Don’t underestimate the impact and importance of user experience and make sure you monitor social media and online chat about your product experience so that you can use that feedback to improve UX, performance and customer satisfaction. Remember happy users tell their friends and family about your product and services and unhappy users tell anyone who will listen!

Everybody’s talking about … core competency

16 May 2014 by Rebecca in Business and finance

In the second of an ongoing series of explorations of key business ideas we investigate a much-abused and little understood term. Core competency is one of those over-used business phrases that often sneak out in high level meetings or when someone is trying to look a little more interesting than they really are. But is it useful or is it just stating the obvious?

Where did it come from?

The phrase core competency was coined by Coimbatore Krishnarao Prahalad, more commonly known as C. K. Prahalad (for obvious reasons) and Gary Hamel – both US based management ‘gurus’ and business authors. It was first referenced and described in a 1990 article they published in the Harvard Business Review called ‘The Core Competence of the Corporation.’

Both Hamel and Prahaled have been consistently regarded by major business publications such as Business Week, The Wall Street Journal and Fortune magazine as amongst the most influential business thinkers in the world.

But what does it mean?

According to Prahalad and Hamel core competency is a concept in management theory that relates to the specific attributes or factors that a business considers as central to the way it operates. A core competency is only a core competency when it meets three criteria:

- It’s not easily replicated by competitors.

- It can be widely used and re-deployed for many products and markets.

- It contributes to the customer’s experienced benefits and the value of the product or service.

Core competencies are particular strengths relative to the competition which provide added value in the eyes of the customer. They can relate to anything from technical expertise to processes and procedures to strong working relationships to innovation to customer loyalty. For example Apple’s user interface is a core competency. People who use Apple products love that they are intuitive and easy to use. So much so that people who are converted to Apple rarely leave Apple. Even though the products have their faults (such as low battery life) and are significantly more expensive than the competition their customers are passionate and loyal about Apple, something that’s not easy to replicate. Their intuitive operating system and user interface also translates across product categories and markets and definitely contribute to the customer’s experienced benefits and perceived value of the products.

Core competencies are particular strengths relative to the competition which provide added value in the eyes of the customer. They can relate to anything from technical expertise to processes and procedures to strong working relationships to innovation to customer loyalty. For example Apple’s user interface is a core competency. People who use Apple products love that they are intuitive and easy to use. So much so that people who are converted to Apple rarely leave Apple. Even though the products have their faults (such as low battery life) and are significantly more expensive than the competition their customers are passionate and loyal about Apple, something that’s not easy to replicate. Their intuitive operating system and user interface also translates across product categories and markets and definitely contribute to the customer’s experienced benefits and perceived value of the products.

Where will I find ‘core competency’ used?

Those who actually know what it means and understand Prahalad and Hamel’s definition use it to describe the ‘collective learning across the corporation’. This collective learning is only possible with outstanding cross-functional cooperation, and a willingness to coordinate and integrate diverse production skills and multiple technologies. Few companies are likely to create world leadership in more than five or six fundamental core competencies.

Those who don’t know what it means but like to throw the term around to impress people and look more knowledgeable than they are often simply use it to describe something a company is particularly good at. But being good at something does not necessarily mean that it’s a core competency. It’s only a core competency when it manifests into core products that serve as a link between the competency and the end user. For example 3M enjoy a core competency in the manufacture of substrates, coatings and adhesives that manifest as a product range that is being added to and developed all the time.

Basically core competency is just Darwin’s theory of evolution but applied to business. As a business grows and evolves it should get better at certain things that help it survive. Those evolutionary improvements that ensure the survival of the fittest should emerge from the collective efforts of the business not just from the individual strengths of the people in the business. That way, they are ‘baked into’ the business. The reality however is often very different: the core competencies within a business are, frequently, actually the core competencies of certain individuals within the business. When those individuals leave, so does the competency.

What’s my core competency?

Most businesses don’t operate around core competencies – they operate around business silos or a portfolio of independent businesses. As a result there is little incentive to share knowledge, experience and competency between the units. Prahalad and Hamel suggest this is an error and actively stops business from developing a significant competitive advantage.

Plus they argue that unless a business understands its core competency it is in danger of losing it without even realising what it’s lost until it’s too late. For example US manufacturers divested themselves of their TV manufacturing business in the 1970s because they believed the market was mature and low cost imports from Asia would render the sector obsolete. In doing so they lost their core competency in video which later handicapped them when everything went digital. Motorola divested itself of its semiconductor DRAM business at 256kb only later to realise they had divested a core competency in electronic data storage and were unable to get back in to the 1Mb market alone. Had they recognised their core competency and the time it took to develop and build it they would have made better strategic choices.

To identify what your core competencies are or could be you need to answer the following questions:

- Is there any part of your manufacture or delivery of your product or service that strongly influences your customer’s willingness to buy? If not it’s probably not a core competency.

- Is the value-adding competency difficult to imitate?

- Is the competency relevant and useful across different products and markets?

As a strategic exercise it is essential to identify and foster core competencies. Not only will this knowledge help direct resources and assist decision making but it will also help to avoid expensive strategic mistakes such as those experienced by the US manufacturers and Motorola.

Five compelling reasons to get into the exercise habit

14 May 2014 by Infinite Ideas in Business and finance

A report by the British Heart Foundation has suggested that high intensity exercise can lead to an increased risk of heart rhythm disturbances. But before you kick off your running shoes and head for the sofa, remember that the benefits of regular exercise outweigh the risks. In fact, a healthy adult should aim to do 2.5 hours of moderate intensity aerobic activity per week. Perhaps you, or somebody you know, needs more convincing. So Kate Cook, author of The Corporate Wellness Bible, has compiled these five compelling reasons for ditching the onesie and donning those long-neglected jogging bottoms.

Why bother to exercise? Here are five compelling reasons

You may hate the idea of it, but taking exercise is life-changing and has real benefits if you’re aiming to lose weight. Once you get into the exercise habit, you won’t want to stop.

- There are loads of different ways of exercising and it doesn’t have to involve being shouted at by an angry man in a tracksuit with a whistle (unless you want it to).

1. Exercise uses up calories. You will lose weight by cutting down on the calories you consume, but if you’re active too, your weight loss will be faster. I love food and working out means I can eat more. It also means that I don’t end up losing any weight, but just maintain the weight I am. When you exercise you build up muscle, which gives you shape; even thin people can use muscle tone. Muscle burns up more energy than fat tissue.

2. Exercise gives you a buzz. You’ve probably heard of the runner’s high, that happy, almost euphoric feeling during an exercise session. Experts put it down to a combination of factors – a release of endorphins, hormones that mask pain and produce a feeling of well-being; the secretion of neurotransmitters in the brain that control our mood and emotions and a plain old sense of achievement. Whatever gives you the high, there’s no doubting the feel-good glow it gives you.

3. Exercise boosts your confidence. Every time you work out or play a sport, you’re doing something positive for yourself, which is mood-enhancing in itself. When you start to see the results in the mirror, your self-esteem rockets. As soon as you see results, you will find it easier to stick to your weight loss plan, too.

4. Exercise reduces your appetite. As well as being a good distraction from the allure of the fridge, exercise slows the movement of food through your digestive system, so it takes longer for you to feel hungry.

5. Exercise helps you keep weight off. From a dietary perspective, the trouble with only tackling your weight loss is that it is usually quite hard to maintain your weight loss in the long term. Once you have reached your goal and are a little less strict with yourself, the weight can begin to come back. Studies have shown that people who have successfully lost weight by taking exercise as well as a sensible approach to food are better at keeping their weight stable longterm.

The key to incorporating exercise into your life is to find something you enjoy. I do believe there’s something for everyone. Some of us love swimming. For others, it’s running or tennis. These days gyms have a huge variety of classes on offer, ranging from the highly choreographed to gentle classes featuring very simple moves. There’s no excuse for at least not trying some of them out. If you really don’t like gyms, there is walking, which is a very good exercise indeed. It is easy to get into the habit of taking regular walks. Just one foot in front of the other, walk out of your door and keep going.