Business and finance

Top 10 management models for your business: #3 Reverse innovation

2 July 2014 by Infinite Ideas in 100+ Management Models, Business and finance

by Fons Trompenaars and Piet Hein Coebergh, co-authors of 100+ Management Models.

Problem Statement

How can reverse innovation create growth?

Essence

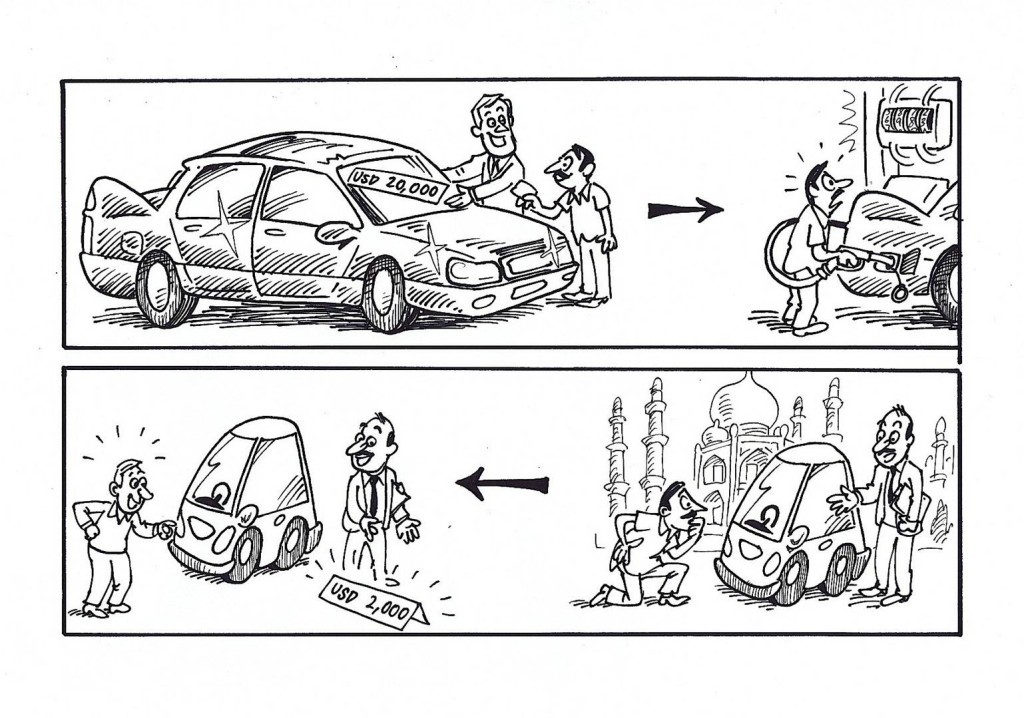

Vijay Govindarajan claims that the need and eagerness in emerging markets for sustainable growth creates an environment for innovation that is superior to the environment in more affluent countries. Govindarajan observes the following evolution: from globalization (richer countries that export what they use themselves) came glocalization (adaption to local needs on a global scale), followed by local innovation (emerging markets increasingly innovate themselves) which is making way for reverse innovation (emerging markets dominate innovation).

Reverse innovation is also called trickle-up innovation or frugal innovation. Govindarajan’s approach builds on Christensen’s theory of how innovation can be disruptive and C.K. Prahalad’s notion that there is a fortune to be made at the bottom of the social pyramid. Govindarajan served as the first professor-in-residence and chief innovation consultant at General Electric, some of the stories that illustrate reverse innovation were developed there, and supported by CEO Jeff Immelt.

How to use the model:

Govindarajan and Trimble’s Reverse Innovation Playbook (2012), covers nine rules ‘that will guide your innovation efforts’, in three categories, that can be summarized as follows:

- Strategy: To grow in emerging markets, innovate, not simply export; grow from innovations in emerging market to other emerging markets; beware of small but fast growing companies in emerging markets.

- Global organization: Move resources to where growth is; create a reverse innovation mindset; focus in these markets on growth metrics.

- Project organization: Stimulate an entrepreneurial ‘start-up’ spirit; leverage resources through partnerships; resolve critical unknowns quickly and inexpensively.

In addition, the Reverse Innovation Toolkit (2012) provides several practical diagnostics and templates to move reverse innovation forward in a company.

Results

Working with the Reverse Innovation Playbook and the Reverse Innovation Toolkit helps creative thinking about unconventional ways to innovate and grow. Evidence that supports this reverse-thinking model is mainly based on how multinational companies operate.

Comments

Like C.K. Prahalad’s theory of how a fortune can be made at the bottom of the pyramid, Govindarajan’s model has received criticism that the theory is not very specific in its approach and that there are only a few showcase examples, in a couple of big companies, to prove the concept, mainly from India and China. In addition, it is not completely unheard of for innovations from emerging markets to become successful, even in richer countries. That does not reduce the challenge that remains for rich countries of finding new ways to grow; in any scenario, this will increasingly be done with the emerging economies. Govindarajan presents a roadmap that at least has the power to take a radically different look at how most (Western) countries do business.

Literature

Govindarajan, V., Trimble, C. (2012) Reverse Innovation: Create Far from Home, Win Everywhere, Boston, Harvard Business Press.

Immelt, J.R., Govindarajan, V., Trimble, C. (2009) How GE is disrupting itself, Harvard Business Review, 87.10, pp. 56–65.

Mahbubani, K. (2013) The Great Convergence: Asia, the West, and the Logic of One World, New York, Perseus.

Getting your message across – Westeros style

1 July 2014 by Rebecca in Business and finance, Entertainment, Game of Thrones on Business

It’s tricky trying to get messages around in the Seven Kingdoms, which seem to lack a basic postal or parcel delivery service, even in the cities – and no one has email. They don’t even have social media. But they make a pretty good job of it.

Long distance message-passing is done by attaching a letter to a raven. According to the books, the value of a carrier-raven was taught to the First Men of Westeros by the Children of The Forest. At this point the birds could talk, which would have ensured an even higher quality of service. A verbal message is encrypted (it exists in the raven’s little brain, and so is harder to intercept without catching every passing raven and torturing it with tiny instruments). It would also have been easier to direct the message to the person who needs to read it, because you could have told the ravens that your letter was urgent, so not to hang around scavenging, for example. This scavenging thing, it seems to me, would be an argument in favour of pigeons. Pigeons fly direct, without stopping to feast on corpses.

With this constraint, the rulers of Westeros have become extremely adept at communicating the Big Ideas. They really get the value of symbolism as a way to make a point efficiently. There’s a phrase in advertising: ‘show, don’t tell’. So, if you want to make thousands of people afraid of you, don’t make long speeches telling them to be afraid, or write lots of nasty letters and attach them to every raven you can find. You do something unexpected that should make them think: watch out.

With this constraint, the rulers of Westeros have become extremely adept at communicating the Big Ideas. They really get the value of symbolism as a way to make a point efficiently. There’s a phrase in advertising: ‘show, don’t tell’. So, if you want to make thousands of people afraid of you, don’t make long speeches telling them to be afraid, or write lots of nasty letters and attach them to every raven you can find. You do something unexpected that should make them think: watch out.

In the disordered world of Game of Thrones, it’s hard to list without giving away spoilers the (almost weekly) moments when some ruler or other follows this plan, so I’ll try to be general. Pouring molten gold on an ambitious person’s head, walking into your husband’s burning funeral pyre and walking out again the next day to show that you’re a bit special, or chopping off the hand of the best swordsman just to show everyone that you can, isn’t necessarily a communications strategy to follow at home or the office. But, in the real world, communications directors who work for our largely-ignored politicians, who weep silently as they arrange another tired visit to a small factory somewhere in the midlands so that their boss can be filmed in a hi-vis jacket pretending to know what the machine does, must wish they lived in Westeros from time to time.

We’ve mentioned Machiavelli before as a link between Game of Thrones and our world. In The Prince, he relates how Pope Alexander VI cleaned up the Romagna province. With a weak government and crime everywhere, the Pope sent Remirro de Orco, his fixer, to clean house by punishing lots of people harshly and cruelly. Everyone hated Remirro, because he was good at what he did: Romagnan crime rates dropped, with a large amount of bloodshed along the way. So, when the job was done, ‘Alexander had him cut in half, and placed one morning in the public square’. Result: everyone liked that there was less crime, and they liked the Pope even more. Remirro showed that no one is above the law, but Alexander showed that no one was above the Pope.

Here lies the difference between sending a message and making a gesture. When a prime minister is photographed pointing at something while wearing a hard hat, it no longer sends us any strong message, because it is what we expect. It delivers no new information. If we even notice, we shrug. A strong message is easiest to convey when it implies new clarity and unexpected change, even if only for a few people. That’s why the most memorable messages often emerge from disorder and confusion, and why most big gestures in our world are so forgettable.

You might also like: What Machiavelli knew and Robb Stark found out; Why Game of Thrones is better than PowerPoint; What Game of Thrones tells us about corporate inbreeding.

What Game of Thrones tells us about corporate inbreeding

25 June 2014 by Rebecca in Business and finance, Game of Thrones on Business

Incest – it’s not about the sex, says Tim Phillips

‘Alongside kinslaying and the violation of guest right, incest is proscribed by every major religion in Westeros,’ the Game of Thrones Wiki tells us, ‘Children born of incest are deemed abominations.’

Didn’t stop them doing it though. Clearly there’s ‘proscribed by every major religion’ and ‘who are you to tell us what to do?’ For those of you not familiar with the Game of Thrones backstory, King Aerys II Targaryen (the Mad King) married his own sister, Queen Rhaella Targaryen. King Aerys made good on his nickname by going insane thanks to inbreeding, and his son Viserys wasn’t all there either.

This, you might conclude, would be an argument against imitating his actions. But Queen Cersei and her brother Jaime Lannister have, even by the beginning of Game of Thrones series 1, been going at it for years. This has the unfortunate consequence that they produce barmy King Joffrey, a sort of psychotic Milky Bar Kid.

This, you might conclude, would be an argument against imitating his actions. But Queen Cersei and her brother Jaime Lannister have, even by the beginning of Game of Thrones series 1, been going at it for years. This has the unfortunate consequence that they produce barmy King Joffrey, a sort of psychotic Milky Bar Kid.

This is a pretty accurate depiction of the sexual behaviour of European royalty through several centuries. For example, John V of Armagnac in the 15th century took up with a young girl called Isabelle who was considered one of the greatest beauties in France. This was controversial because there had been talk of marrying her to Henry VI of England before he stepped in. It was even more controversial because she was also his sister. After they had two children John V promised to keep his codpiece buttoned while his sister was around, so the kerfuffle didn’t exactly die down when they got married (claiming the Pope had told them it was OK), and had a third child.

The literal aristocrats of incestual ick were undoubtedly the Habsburgs, who bred so enthusiastically with their cousins that, by the 17th century King Charles II was ‘physically disabled, mentally retarded and disfigured’. Academic studies calculate that Hapsburg marriages had up to 25% of genes in common.

You don’t have to be a disciple of Sigmund Freud to be aware that incest fantasies are common; every internet porno site has an incest category. Well, that’s what PEOPLE TELL ME. But the Habsburgs weren’t being kinky. Royal incest is about power. It kept the fortune in the family – if your extended family was also in charge of the country next-door, then a political alliance meant a family wedding, whether you were into that sort of thing or not.

So, if we concentrate on the sex, we’re missing the point. This is about power, and keeping power close. Power influences the way the cake is cut: the more you concentrate power, the more of the cake you keep. What psychologists call ‘other-regarding behaviour’ is more common among those genetically closer to us, or those with a similar world view.

It often isn’t a plan, but an outcome of a natural (though misguided) thought process, in which we trust and value people who look and talk like us. People in power share power with their ‘family’. Few discriminate consciously, but only a small group of the population has the social capital (confidence, education, powerful friends and common experiences) to be part of the ‘in group’. Are these always the best people to wield power? Your opinion may be influenced by whether you are in that group or not.

We assume that shareholder capitalism places controls on CEOs and their executive officers, just as royal alliances between families were meant to moderate the behaviour of each ruler: but when the powerful actors are ‘family’, the opposite can often be the case.

This survey shows how corporate dynasties intermarry by sitting on each other’s boards. One result: a small group effectively decides one another’s compensation, and we all know how executive pay has ballooned in the last 30 years at a far greater rate than profits have increased. That’s not criminal. But scandals at Enron, WorldCom and many others – in which the performance of a supine board has been shown to be a contributing factor – shows what can happen when intermarriage gives too much power, with too little oversight, to the King Joffreys of the corporate world.

Tim Phillips is author of Niccolo Machiavelli’s The Prince, Bertrand Russell’s The Conquest of Happiness, and Charles Mackay’s Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds.

You might also like: What Machiavelli knew and Robb Stark found out; Why Game of Thrones is better than PowerPoint.

Is God a futurist?

24 June 2014 by Infinite Ideas in Business and finance, Codebreaking our future

by Michael Lee, author of Codebreaking our future

After reading the title of this blog, you may well be asking two questions: ‘Who is God?’ and ‘What is a futurist?’.

Believers in God know in whom they believe, while for those who don’t have religious beliefs, God is more like the Hypothetical One they don’t acknowledge as real. So let’s move on to the slightly less speculative question of the two, namely, ‘What kind of beast is a futurist?’

In the broadest sense, a futurist studies, analyses and forecasts the future in a disciplined, methodically sound way. The futurist’s currency is foresight, a systematic anticipation of the shape, structure and character of the emerging world. For many theoretical and historical reasons, the study of the future is still a sleeping giant.

In my view, systematic anticipation of the future, which I prefer to call futurology, is the next great science. But that is another topic covered in other blogs and published work. This blog is about God and the future.

We all remember that Einstein claimed that God does not play dice with the world and most readers will also know that Newton was just as deeply interested in theology as he was in physics and mathematics, possessing over two dozen Bibles at the time of his death. And what all science unquestionably shows is that the universe operates intelligently, following laws of nature and evolution. So one can either conclude that such intelligence of design and lawfulness of behaviour derives from a superior intelligence we call God or has emerged spontaneously from nothing/something. Each person makes his or her own determination.

As a futurist, what’s important is the extent to which the way in which science has modelled the universe may have enabled us to make rational predictions about future states. Mathematical genius Pierre-Simon de Laplace wrote in his ground-breaking 1814 essay, A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities : ‘Present events are connected with preceding ones by a tie based upon the evident principle that a thing cannot occur without a cause which produces it … We ought then to regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its anterior state and as the cause of the one which is to follow … The regularity which astronomy shows us in the movements of the comets doubtless exists also in all phenomena.’[1]

Since we are focusing here on God (or the Hypothetical One, if you would prefer) and the future, one might want to carry out a futurological exercise predicting what is likely to happen to religion – and the forces and institutions of religion – throughout the remainder of the twenty-first century. Using Laplace’s logic of probability, we would need to start by looking at the past and present state of religion in the world – it’s evolutionary trajectory – and then globally contextualize that pattern over time within the multiple dimensions of our world – social, cultural, demographic, political, environmental, economic, etc. So one would evolutionize and contextualize the data about religion as the basis for futurological conclusions.

In studying the future of religion in this way, we’d get glimpses into the future of God and his role in our world over the next few generations. That would require a major in-depth study well beyond the scope of this blog. But we can certainly provide an appetizer. Then an answer to the question posed in the title will be offered.

The most surprising fact about religion today, especially for those who live in largely secular Western societies from North America to New Zealand, from Europe to Australia, is that religious belief in the world as a whole is growing quite strongly, while the growth of non-religious belief has fallen well behind the average rate of global population growth, that is, the role of secularism is declining, despite the immense impact of Western-style economic and cultural globalization.

First, let’s check out the facts about human belief in today’s world (as at June 2010).

World population distribution of belief systems, with current annual growth rates*

|

Belief system |

Percentage of world population |

Current annual growth rate in belief system’s population size |

|

Christianity |

32.29% |

1.2% |

|

Islam |

22.90% |

1.9% |

|

Hinduism |

13.88% |

1.2% |

|

Non-religious |

13.58% |

0.7% |

|

Buddhism |

6.92% |

1.3% |

|

Chinese religions |

5.94% |

0.0% |

|

Ethnic religions |

3.00% |

0.6% |

|

Sikh religion |

0.35% |

1.4% |

|

Judaism |

0.21% |

0.3% |

|

Other |

0.32% |

N/A |

In the table above, only belief system population groups growing at a rate higher than 1.2% are growing faster than the world’s population. Non-religious people make up only 13.58% of the world’s population and that slice of the global pie is declining. This means that decades of economic and cultural globalization by a largely secular West have not brought about a concomitant, commensurate spread of non-religious belief.

The four largest religious belief system groups, namely, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism, together make up 75.99% of the world’s population, clearly a substantial majority.

In a nutshell, then, belief systems of the world are divided up as follows:

Top four religions by size = 75.99%

Non-religious population = 13.58%

Other = 10.43%

Figure 1: Comparative size of religious and non-religious populations in the world (2010)

Figure 1 shows that the Hypothetical One is not in any danger of being forgotten any time soon.

Furthermore, the future of religion will almost certainly be reinforced by a fundamental and intensifying global demographic trend, namely population decline. Depopulation is now occurring in many nations across the world. Dr. Phillip Longman, demographer and author of The Empty Cradle (2004) points out that global fertility rates are half what they were in 1972. It is thought that total human population may peak in 2050 at nine billion and thereafter decline. Bearing in mind that the human replacement fertility rate is 2.1 children per women, it’s alarming that 62 countries, making up almost half the world’s population, now have fertility rates at, or below, this rate, including most of the industrial world and Asian powers like China, Taiwan and South Korea.[2] At the start of the twentieth century, by contrast, the global fertility rate was higher than five children per woman of child-bearing age! The world’s population growth rate has fallen from 2% p.a. in the late 1960s to just over 1% today, and is predicted to slow further to 0.7% by 2030 and then 0.4% by 2050.[3] Most European countries are on a path to population ageing and absolute population decline[4]; in fact, no country in Europe is demographically replacing its population.[5]

Given this grim demographic picture, the role of pro-natal belief system population groups, including religious communities, is likely to become much more significant in the evolution of the human species. In the coming decades, humanity will be wrestling to avoid the disastrous socio-economic consequences of declining populations.

To halt population decline, radical change in values and lifestyle practices will eventually be needed. Human families, and their critical procreative role, will need to be strengthened.

The increasing influence of religion on society, of course, does not prove that God is a futurist, that is, a being who foresees the future in all its multi-dimensional complexity. Yet one of humanity’s first attempts to study the future was ancient prophecy. The prophets of the Old and New Testaments looked forward to a new world and, at times, to the projected end of the world itself. The Mayan civilization had deep insights into large-scale cycles of time, enabling them to make some far-reaching prophecies, including about a society which would one day fatally debase its environment.

The Bible is decisively future-facing in its outlook on the world, from Genesis (promising, for example, a long line of future generations from Abraham’s seed) to the overtly apocalyptic Book of Revelation. Many commentators believe Western civilization drew inspiration, in its rise to global power, from the Bible’s messianic, idealistic message, for example in the renowned Protestant work ethic geared towards building an earthly kingdom to the glory of God.

Given that religious belief systems are increasing in influence despite decades of secular economic globalization, it’s my perspective that the future of God looks promising. And, given that biblical theology is inherently prophetic and eschatological, one might even be tempted to say: the future of a futuristic God is bright.

To many in the world, frightened by religious extremism such as seen in the recent ISIS rampage across Iraq, this spectre of ascendant religion in decades to come may not appear to be good news. There is time, however, to inculcate rationalism, central to the objective discipline of futurology, within the public domain of shared common reality, in order to temper the emotional excesses displayed by the warped politics of some radical brands of religion. We need to move beyond ideology in public governance towards science as the great problem-solver. Slowly, I sense, a giant new science, with deep philosophical roots in the human past, is awakening.

Acknowledgments

Laplace,P.S. 1814. A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities. Cornell University Library.

Longman, P. 2004. The Empty Cradle. New York: Basic Books.

Magnus, G. 2009. The Age of Ageing. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia).

Mandryk, J. 2010. Operation World (Seventh Edition). Colorado Springs: Biblica Publishing.

*Data taken from the Seventh Edition of Operation World based calculated at June 2010

[1] Pierre Simon de Laplace, A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities

[2] Magnus, The Age of Ageing (2009) 40.

[3] Magnus, The Age of Ageing (2009) 33.

[4] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 61.

[5] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 177.

Are the high salaries of footballers like Luis Suárez justified?

23 June 2014 by Rebecca in Business and finance, Football Business

By Tsjalle van der Berg, author of Football business

Edson Arantes do Nascimento, who you know as Pelé, had the nickname ‘O Rei do Futebol’. He will forever be associated with one particular piece of skill at the 1970 World Cup in Mexico. From the halfway line, the Brazilian fired the ball over the Czech keeper, who was way off his line and turned to see the ball dip just in time. Nothing like it had ever been seen before during a World Cup match. Unfortunately I was not allowed to watch it on TV as a child in 1970 because the match was broadcast late at night. So I was very pleased when footage from the game was recently shown on TV. And it was worth watching. The keeper was not even that far out of his goal, and the trajectory of the ball was even more impressive than I had imagined. Pelé even had a surprise in store for me: the ball went just wide.

These days you see the occasional lob like Pelé’s, and now and then one even goes in. In 2014, Wayne Rooney scored a fantastic goal like that against West Ham United. Does that make him better than ‘O Rei do Futebol’? Sadly, no. What made Pelé’s lob so special was that he was the first who dared to try a lob in an important match. It may well be that the Pelé of old would have struggled in today’s football. Today’s players are physically and tactically stronger. No matter. Pelé gave people pleasure because he was better than his contemporaries.

What would have happened if the hundred best players of all time had never been born? Other players would have taken their places as superstars. Someone else would have been the first to lob the keeper from the halfway line. Of course we would have had to do without a few delightful pieces of skill, such as Robin Van Persie’s beautiful header against Spain during the present World Cup. Still, the pleasure had by all the fans put together would not have been much less as a result. Because football’s main attraction is the excitement and the contest against the opposition.

What does this mean for the debate about players’ wages? Are Messi’s millions justified because he entertains so many people and because, partly as a result, people are prepared to pay so much to watch Barcelona on TV and buy club merchandise? From the individual perspectives of Barcelona and Messi, there is something to be said for that view. But you can also take a broader view. Without Messi, someone else would be the world’s best payer, and that player would also be much loved. The ultimate reason fans spend a lot of money on football is that the sport is so popular. And that is largely due to the volunteers, supporters and rather poorly paid players of a previous era who made football what it is today.

So in my opinion, the salaries of present-day players are too high. It’s not the stars that make football. It’s football that makes the stars.

Without Luis Suárez, Liverpool would not have finished second last season. They might not even have qualified for the lucrative Champions League; Everton could have qualified instead. So from Liverpool’s perspective, it is quite justified that Suárez earns many millions a year. And for the fans of the club, Suárez is really worth his salary as he has given them so much joy. Moreover, he did a lot to brighten up the lives of his fellow countrymen by helping Uruguay beat England last week. No-one in Uruguay will be begrudging him his salary now. But to the world as a whole, his value is far more limited. For instance, Uruguay’s joy after the two Suárez goals stands in contrast to the pain of the losing country – and Suárez is responsible for that too. Perhaps all the suffering he has caused should be docked from his wages …

Without Luis Suárez, Liverpool would not have finished second last season. They might not even have qualified for the lucrative Champions League; Everton could have qualified instead. So from Liverpool’s perspective, it is quite justified that Suárez earns many millions a year. And for the fans of the club, Suárez is really worth his salary as he has given them so much joy. Moreover, he did a lot to brighten up the lives of his fellow countrymen by helping Uruguay beat England last week. No-one in Uruguay will be begrudging him his salary now. But to the world as a whole, his value is far more limited. For instance, Uruguay’s joy after the two Suárez goals stands in contrast to the pain of the losing country – and Suárez is responsible for that too. Perhaps all the suffering he has caused should be docked from his wages …

Dutchman Tsjalle van der Burg is an economist and Robin Van Persie fan

Top 10 management models for your business: #2 Multiple stakeholder sustainabilty

18 June 2014 by Infinite Ideas in 100+ Management Models, Business and finance

by Fons Trompenaars and Piet Hein Coebergh, co-authors of 100+ Management Models.

Problem Statement

How can I assess the most significant organizational dilemmas resulting from conflicting stakeholder demands and also assess organizational priorities to create sustainable performance?

Essence

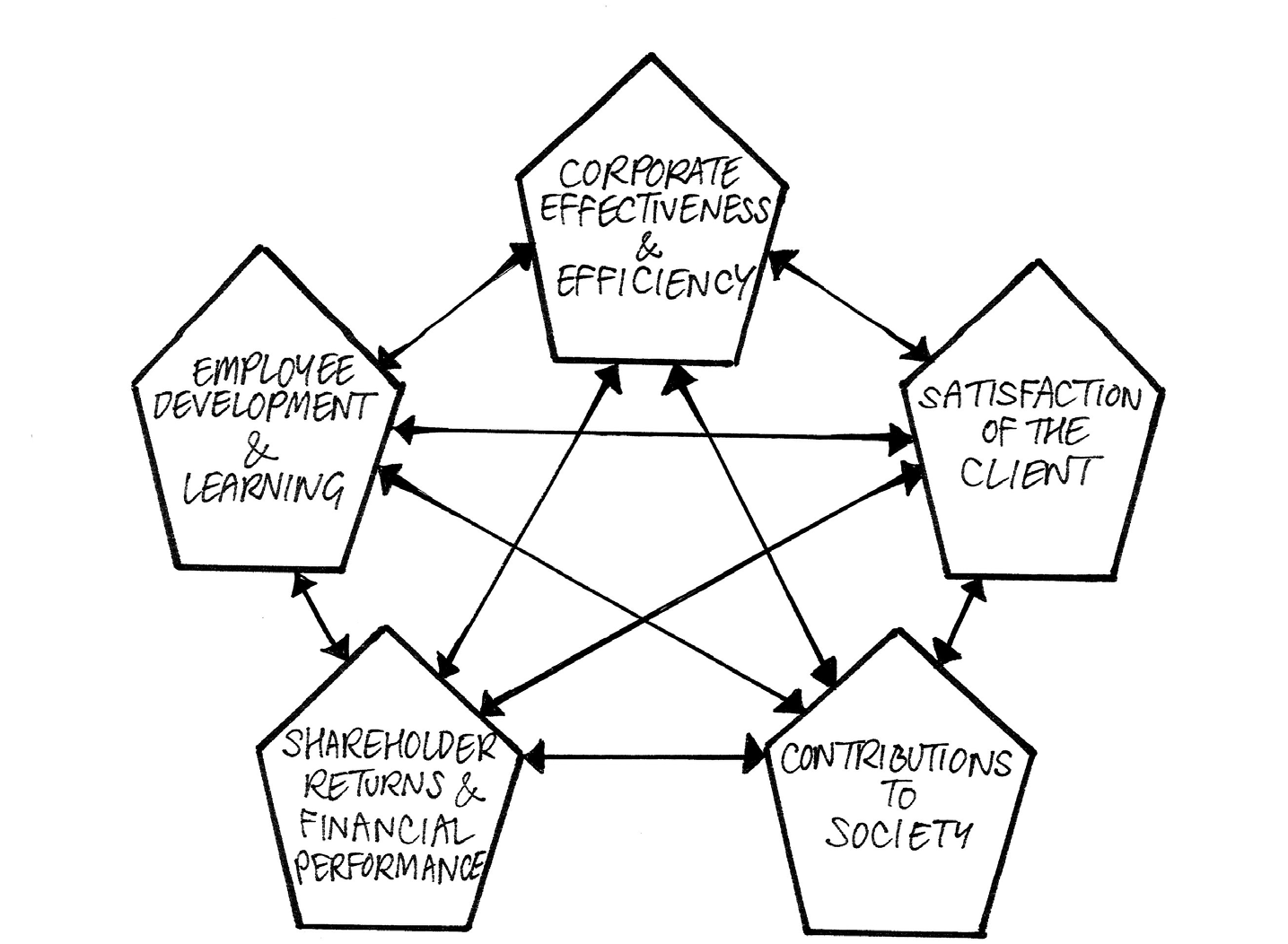

Organizational sustainability is not limited to the fashionable environmental factors such as emissions, green energy, saving scarce resources, corporate social responsibility, et cetera. The future strength of an organization depends on the way leadership and management deal with the tensions between the five major entities facing any organization: efficiency of business processes, people, clients, shareholders and society. The manner in which these tensions are addressed and resolved determines the future strength and opportunities of an organization. This model proposes that sustainability can be defined as the degree to which an organization is capable of creating long-term wealth by reconciling its most important (‘golden’) dilemmas, created between these five components. From this, professors and consultants Fons Trompenaars and Peter Woolliams have identified ten dimensions

Model 7: Multiple ultiple stakeholder stakeholder sustainability sustainability sustainability , Fons Trompenars and Peter Woliams Woliams Woliams (2010)

57

consisting of dilemmas formed from these five components because each one competes with the other four.

How to use the model:

The authors have developed a sustainability scan to use when making a diagnosis. This scan reveals:

- The major dilemmas and how people perceive the organization’s position in relation to these dilemmas.

- The corporate culture of an organization and their openness to the reconciliation of the major dilemmas.

- The competence of its leadership to reconcile these dilemmas. After the diagnosis the organization can move on to reconciling the major dilemmas that lead to sustainable performance. To this end, the authors developed a dilemma reconciliation process.

Results

To achieve sustainable success, organizations need to integrate the competing demands of their key stakeholders: operational processes, employees, clients, shareholders and society. By diagnosing and connecting different viewpoints and values their research and consulting practice results in a better understanding of:

ll. The key challenges the organization faces with its various stakeholders and how to prioritize them.

ll. The extent to which leadership and management are capable of addressing the organizational dilemmas.

ll. The personal values of employees and their alignment with organizational values.

These results help an organization define a corporate strategy in which crucial dilemmas are reconciled and ensure that the company’s leadership is capable of executing the strategy sustainably. It does so while specifically addresing the company’s wealth creating processes before the results show up in financial reports. It attempts to anticipate what the corporate financial performance will be, some six months to three years in the future, as the financial effects of dilemma reconciliation are budgeted.

Comments

The sustainability scan reconciles the key dilemmas that corporations face today and tomorrow. It takes a unique approach to making strategic decisions that are tough as well as inevitable with the goal of realizing a profitable and sustainable corporate future. Consulting firm Trompenaars-Hampden Turner offers an elaborate set of tools, of which a substantial part is available at no cost, to make this approach happen. The leading partners of this firm

Sustainability ustainability ustainability

58

have strengthened the approach in dozens of academic articles and books. The fact that their approach is rather closely attached to their consulting practice does limit its dispersion among other practitioners and academics.

Literature

Buytendijk, F. (2010) Dealing with Dilemmas: Where Business Analytics Fall Short, New York, John Wiley.

Hampden-Turner, C. (1990) Charting the Corporate Mind: Graphic Solutions to Business Conflicts, New York, The Free Press.

Trompenaars, F., Woolliams, P. (2009) ‘Towards a Generic Framework of Competence for Today’s Global Village’, in: The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence, ed. D.K. Deardoff, Thousand Oaks, Sage.