Business and finance

Top 10 management models for your business #5: six stages of social business transformation

30 July 2014 by Infinite Ideas in 100+ Management Models, Business and finance

Fons Trompenaars and Piet Hein Coebergh, co-authors of 100+ Management Models.

Problem Statement

How can organizations optimize engagement with their target audience through social media?

Essence

Charlene Li and Brian Solis, consultants and authors on social media and digital marketing, have developed a leading body of knowledge on how organizations can deal with the rising importance of transparency and engagement. Their model builds on the ideas of Groundswell (Li and Bernoff, 2008), describing how people increasingly connect with each other to be informed, rather than listening to organizations. The book describes how companies are becoming less able to control customers’ attitudes through market research, customer service and advertising. Instead, customers increasingly control the conversation by using new media to communicate about products and companies. Li and Solis observe that organizations connect with customers by taking the following steps:

- Planning – ‘Listen and learn’: Ensure commitment to get the business social.

- Presence – ‘Stake our claim’: Evolution from planning to action, establishing a formal and informed presence in social media;

- Engagement – ‘Dialogue deepens relationships’: Commitment where social media is seen as a critical element in relationship-building;

- Formalized – ‘Organize for scale’: A formalized approach focuses on three key activities: establishing an executive sponsor, creating a centre of excellence and establishing organization-wide governance;

- Strategic – ‘Become a social business’: Social media initiatives gain visibility and real business impact.

- Converged – ‘Business to social’: Having cross-functional and executive support, social business strategies start to weave into the fabric of an evolving organization.

How to use the Model

The model can serve as a roadmap for organizations to improve their engagement with stakeholders, especially through social media. A model to measure current engagement of an organization with its target audience is Li’s Social Technographics Ladder (Li and Bernoff, 2008). The ladder identifies people according to how they use social technologies, classified as creators, critics, collectors, joiners, spectators and inactives. Taken together, these groups make up the ecosystem that forms the groundswell. Each step on the ladder represents a group of consumers more involved in the groundswell than the previous steps. To join the group on a step, a consumer need only participate in one of the listed activities. Steven van Belleghem, from Vlerick Business School, has developed a three-step approach to setting up and managing a conversation on any level of the Technographics Ladder: observe the conversation you perceive as relevant as an organization, facilitate the conversation you want to create and join the conversation as a peer.

Results

Implementing the model as a roadmap towards more social engagement requires leadership in managing this change process. The authors of Groundswell suggest the POST approach for change, working with people (assess social activities of customers), objectives (decide what you want to accomplish), strategy (plan for how relationships with customers will change) and technology (decide which social technologies to use).

Comments

The impact of the Internet on society in general, and of social media in particular, has not created a paradigm shift in social science, as yet. In academia, the information revolution and ongoing digitization is mostly being explained by classic models, of which the most powerful are included in this book. Competing with these classics is a burgeoning variety of authors and consultants who publish all sorts of new models, mainly through media where displaying academic evidence is considered of low importance. The books of Li and Solis may not represent the state of the art in academia, but they do offer research-based, new, practical and appealing approaches in defining digital marketing.

Literature

Duhé, S. ed. (2012) New Media and Public Relations, 2nd Ed., New York, Peter Lang

Publishing.

Li, C., Bernoff, J. (2011) Groundswell, expanded and revised edition: Winning in a World

Transformed by Social Technologies, Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

Solis, B. (2011) Engage! The Complete Guide for Brands and Businesses to Build, Cultivate, and

Measure Success in the New Web, Hoboken, John Wiley.

The Depopulation Time Bomb

28 July 2014 by Infinite Ideas in Business and finance, Codebreaking our future

by Michael Lee, author of Codebreaking our future

The future of nations is not written in the stars but in their demographics. In particular, a futurist can study national fertility rates, urbanisation trends and the age structure of population groups to get a picture of a country’s long-term future.

Remarkable polymath Benjamin Franklin was one of the founding fathers of America and, back in the 1770s, he enjoyed unbridled optimism about the future of his nation, which at the time was still overwhelmingly rural and comparatively “backward”. Why, then, was his prognosis so rosy? America’s birth-rate, he reasoned, was double that of Europe’s. Today, the position in America has been reversed and there are no grounds for any of Franklin’s demographic optimism. Between 1990-2002, the crude birth rate in the US declined by 17%. Similar declines are happening right across the developed and developing world. Before discussing this in more detail, let’s paint in broad brushstrokes the background for understanding the world’s current demographics.

The stand-out feature of a general picture of population trends is the astonishing discrepancy between underlying demographics and the current distribution of global power and wealth. It’s this disconnect which highlights the spaces in which the international order is going to shift in the coming decades. One can map international influence against population profiles to highlight this incongruity.

|

Region |

Total population (in millions) |

Annual rate of increase of population (%) 2010-2015 |

|

Asia (including Middle East) |

4,254,524 |

1.0 |

|

Africa |

1,083,524 |

2.5 |

|

Europe |

741,971 |

0.1 |

|

Latin America & the Caribbean |

609,807 |

1.1 |

|

North America |

352,471 |

0.8 |

|

Oceania (Australia, NZ, Polynesia, etc) |

37,775 |

1.4 |

|

World |

7,080,072 |

1.1 |

Table 1: World Population at 2012

(Sources: UN Demographic Yearbook 2012;

UN Population & Vital Statistics Report Series A, Vol. LXVI)

Observe in Table 1 that only Africa’s rate of population increase is significantly higher than the rather meagre global average of 1.1% per annum. Populations outside Africa and parts of Asia are just not increasing with any kind of vigour. You will also note that Africa and Asia (including the Middle East) together make up just over 75% of the world’s population at 5,338,048. By contrast, Europe makes up 10.5% of the world, Latin America & the Caribbean 9%, North America 5% and Oceania 0.5%. But something is interesting here. There is a complete mismatch between these population sizes and the distribution of global geo-political power today.

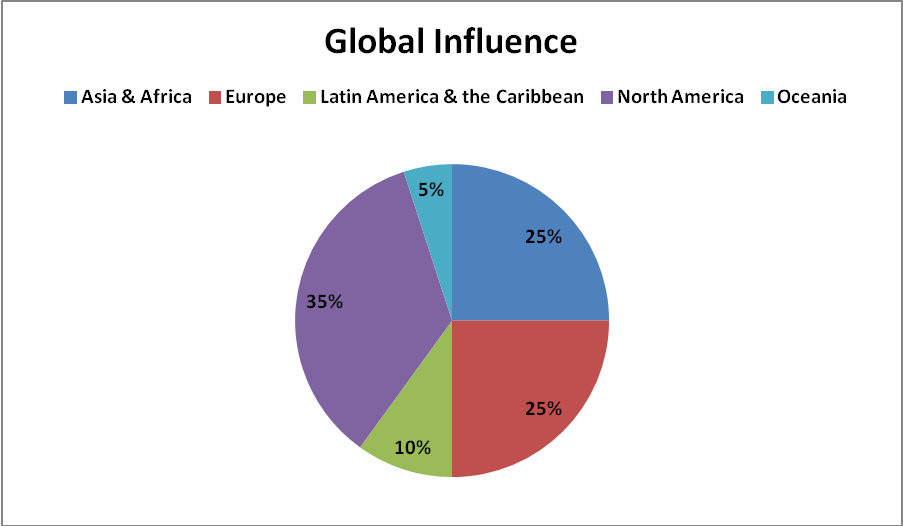

For example, if one estimates global economic and political influence by regions, it might well look something like this:

Figure 1: Estimated Global Influence by Region (Source: author)

In Figure 1, the dominant powers are North America and Europe, with 35% and 25% of global influence respectively. Next comes Africa and Asia together providing approximately 25% of the influence, Latin America & the Caribbean a further 10% and Oceania fighting above its demographic weight division at 5%.

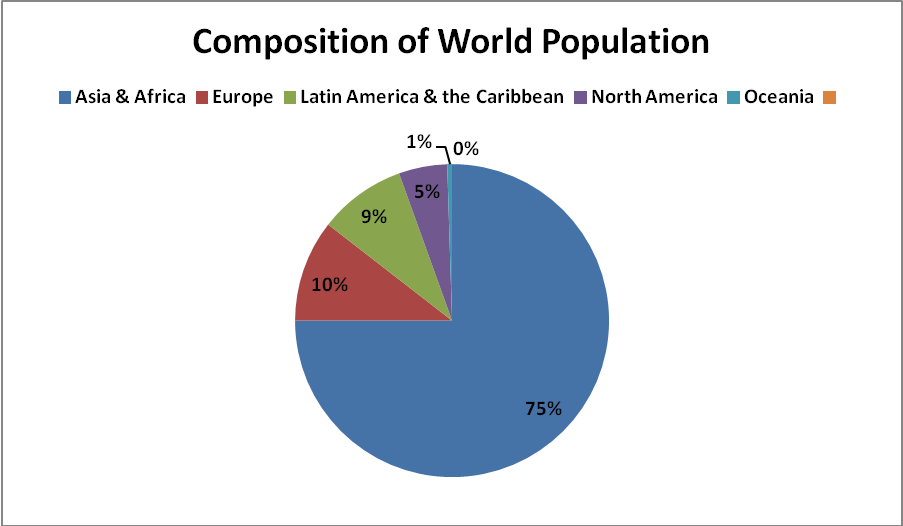

Now, let’s turn to underlying population sizes for a completely different picture.

Figure 2: Composition of World Population by Region (Source: author)

North America, with 35% of the influence, has 5% of the global population. Europe, with 25% of the influence, has 10.5% of the population. Africa and Asia, with only 25% of the influence, have 75% of the population. Latin America & the Caribbean have 10% of the influence and 9% of the population. And Oceania has 5% of the influence but only 0.5% of the population. This skewed distribution of power is bound to change on a large scale throughout this century.

Population sizes indicate the potential magnitude of an economy and its markets, in the sense that its citizens are the producers, the consumers and the tax payers. Of course, urbanisation and development levels have to be factored in, too, as do resources. In addition, the age structure of the population, whether it is young and growing or ageing and declining, is a key consideration. Crudely, though, the following mapping of global influence over population size provides a context for speculation on future shifts of influence, highlighting from which regions they are most likely to come.

|

|

Relative Influence |

Relative Size |

Probable long-term shift in influence |

| Asia and Africa |

25% |

75% |

Greater |

| Europe |

25% |

10.5% |

Lower |

| Latin America & the Caribbean |

10% |

9% |

Equal to |

| North America |

35% |

5% |

Lower |

| Oceania |

5% |

0.5% |

Lower |

Table 2: Relative influence versus size to indicate potential shifts of influence (Source: author)

Table 2 is only a rough guide to potential future shifts of international influence based on the simple equation that size matters when it comes to economies, especially, as mentioned, when seen in the context of developmental factors and the age profile of the population in question. (You are welcome to play around with the figures for estimated global influence by region to come up with your own “map”). The differentials between influence and size in Table 2 are:

Africa & Asia = 50% +

Europe = -14.5%

Latin America & the Caribbean = -1%

North America = -30%

Oceania = -5.5%

These differentials show the conditions for extensive changes of power in the coming decades. It’s an X-ray of a future changing international order.

The population sizes for the countries in the BRICS trade bloc of developing economies, for example, are:

Brazil: 190.7 million

Russia: 143.4 million

India: 1.2 billion

China: 1.3 billion

South Africa: 51 million

If one takes the “CIA” regions of the world – China/India/Africa – the population sizes are:

China: 1.3 billion

India: 1.2 billion

Africa: 1 billion

= 3.5 billion (about 50% of world’s population)

The size of potential new and extended markets in these CIA regions is vast and there is likely going to be an increasing wealth base and growing influence across these regions.

I regard demographics as one of the most impressive of all the social sciences. This discipline largely deals with real, socially significant population data. Its figures are squarely based on facts. This allows for robust, evidence-based reasoning. With demographics, we’re looking into a radar of the future.

Which brings me to a disturbing reality I wish to share with you today. Like the inferences made from the data in Table 2, this fact may appear, at first glance, to be counter-intuitive. I referred earlier in looking at Table 1 to the meagre global rates of annual population increases this century. Birth-rates are falling all over the world in deeply entrenched trends rooted in the very nature of modern society. A human depopulation time bomb is ticking.

Human population growth is decreasing at a rate which will imperil the global economy, destabilise some societies and ultimately threaten humanity’s prospects for survival.

US demographer and senior fellow at the New America Foundation, Phillip Longman, explains: “World population growth has already slowed dramatically over the last generation and is headed on course for absolute decline. Indeed, forecasts by the United Nations and others show the world population growth rate could well turn negative during the lifetimes of people now in their 40sand 50s.”[1]

Longman is warning us that population growth for humanity is likely to turn negative around mid-century. This means the world’s total population size would start to decrease in absolute terms. If such a trend ever became irreversible, it would eventually lead to the extinction of the human race.

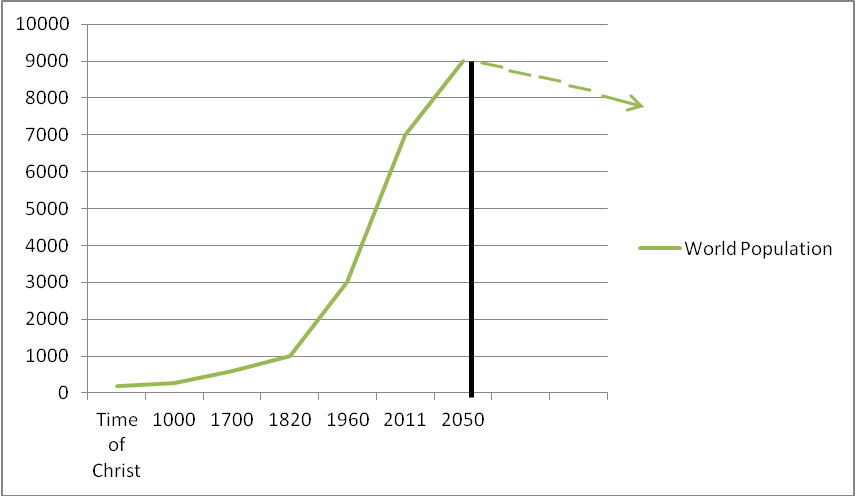

Figure 3: The rise of world population to its projected peak in 2050

Figure 3 indicates that the total human population may peak in 2050 at nine billion and thereafter decline year after year, decade after decade, generation after generation. It’s not a comforting thought that Population Peak for the human race is probably just up ahead of us.

Shrinking nations and families conjure up nightmarish scenarios of a declining world population. If sub-replacement fertility rates across the world continue compounding century after century, it’s a mathematical certainty that the human race will one day become extinct.

The core fact is that global fertility rates are half what they were in 1972. This is disconcerting given that fertility rates are what keep the human race reproducing itself. The fall in global fertility is the key global problem to address in this century.

The following data together brings home the extent of this trend, bearing in mind that the replacement fertility rate is 2.1 children per women and that, at the start of the 20th century, the global fertility rate was higher than five children per woman of child-bearing age:

- The world’s population growth rate has fallen from 2% p.a. in the late 1960s to just over 1% today, and is predicted to slow further to 0.7% by 2030 and then 0.4% by 2050.[2]

- 62 countries, making up almost half the world’s population, now have fertility rates at, or below, the replacement rate of 2.1, including most of the industrial world and Asian powers like China, Taiwan and South Korea.[3]

- Most European countries are on a path to population ageing and absolute population decline[4], in fact, no country in Europe is demographically replacing its population[5] – “If Europe’s current fertility rate of around 1.5 births per woman persists until 2020, this will result in 88 million fewer Europeans by the end of the century.”[6]

- Spain has the lowest fertility rates ever recorded

- Russia, and most of the Balkans and Eastern Europe, are facing a fall in the size of their populations of between 13-35 % in the next four decades, with China’s starting to fall between 2030- 2035 and Thailand’s after about 2040[7]

- Japan’s fertility rate is 1.4 children per women, one of the lowest

- China’s fertility rate is between 1.5 and 1.65

- Cuba has one of the lowest fertility rates in the world

- Italy, once the seat of the Roman Empire that ruled most of the known world, has a disastrously low fertility rate of 1.2

- Since 1975, Brazil’s fertility rate has dropped nearly in half to just 2.27 children per woman[8]

- By mid-century, China could lose 20-30% of its population every generation[9]

- By 2050, the median age of the world’s population will be 38 years, in Europe, 47, China, 45, in North America and Asia about 41[10]

It’s the scale of the depopulation problem that is daunting. Longman explains: “All told, some 59 countries, comprising roughly 44 percent of the world’s total population, are currently not producing enough children to avoid population decline, and the phenomenon continues to spread. By 2050, according to the latest United Nations projections, 75 percent of all countries, even in underdeveloped regions, will be reproducing at below-replacement levels.”[11] Consequently, he’s expecting the world population to peak around 2050.[12]

A silent demographic revolution is happening to our world.

Associated with human depopulation is the inevitable ageing of the global population. [13] This will have dramatic, long-term impacts on economies. Population trends drive changes across a range of fields from economics and finances to politics, from sociology to international relations. Ageing populations spend less and produce less, depressing business demand. Societies in Asia, Europe and the Americas are turning grey and there are concerns about the drain on public expenditure and the loss of national productivity which will ensue. Population ageing will place added burdens on both government finances and the working generation. This affects the economy directly: “There is a reasonably robust theory…that suggests people accumulate wealth between the ages of 30 and 60 for retirement, after which they tend to save less or ‘dis-save’.”[14]

Longman establishes a link between demography and economics early in his landmark book The Empty Cradle: “Capitalism has never flourished except when accompanied by population growth.”[15] Businesses, he says, go where populations are growing, not where they’re declining. Why? Because there’ll be more demand for their goods: “More people create more demand for the products capitalists sell, and more supply of the labor capitalists buy.”[16] Here’s the simple equation illustrating the loop between demographics and economics: “Because of today’s low birth-rates, there will be fewer workers available in the future to produce the goods and services consumed by each retiree.”[17]

And here’s the result for the economy: “The working population of the United States essentially will wind up paying one out of every five dollars it earns just to support retirees, while simultaneously trying to finance more and more years of higher education…”, creating financial disincentives for families to produce many children.[18]

A stagnant population, in other words, is likely to produce a stagnant economy. When there’s depopulation, investment and business confidence eventually vanish, along with economic growth: “Without population growth providing an ever increasing supply of workers and consumers, economic growth would depend entirely on pushing more people into the work force and getting more out of them each day.”[19]

In sum, then, there are significant declines in birth-rates right across the world, sometimes well below replacement levels. The depopulation time bomb isn’t science fiction, it’s a matter of demographic fact.

The populations of major nations like Japan and Russia are already shrinking in size at worrying rates.

Japan, once the 2nd largest economy in the world, is now into its third decade of sluggish growth due to its twin curses of declining population and productivity and population ageing. In desperation, it’s turning to robotics to inject new life into its zombie economy.

Similarly, Russia is facing its own depopulation bomb. It’s estimated to lose between 13-35% of its population size in the next four decades. In 1937, Russia had a population of 162 million. This has fallen to 142 million. It’s predicted to fall further to about 80-90 million by mid-century. Between 1937-2050, then, the country’s population size could have halved. At a time when it’s once again emerging as an energy giant, its demographics, ironically, are undermining its future prospects. The demographic challenge of halting depopulation will be complicated by the presence of an estimated 14.5 million Muslims in the country which may threaten unity and heighten ethnic tensions within its borders.

As a futurist, I have to admit my blood runs cold when I consider such overwhelming and conclusive evidence of humanity losing its appetite to reproduce itself.

Acknowledgments

Longman, P. 2004. The Empty Cradle. New York: Basic Books.

Magnus,G. 2009. The Age of Ageing. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons..

“Population and Vital Statistics Report, Series A Vol. LXVI”, Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Department of Economic an d Social Affairs Statistics Division. See http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/default.htm

UN Demographic yearbook 2012 (63rd Issue), New York: 2013.

[1] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004)7.

[2] Magnus, The Age of Ageing (2009) 33.

[3] Magnus, The Age of Ageing (2009) 40.

[4] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 61.

[5] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 177.

[6] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 67.

[7] Magnus, The Age of Ageing (2009) 158.

[8] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 32.

[9] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 11.

[10] Magnus, The Age of Ageing (2009) xxi-xxii.

[11] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 26.

[12] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 27.

[13] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) xiii.

[14] Magnus, The Age of Ageing (2009) 114.

[15] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 4.

[16] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 4.

[17] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 19.

[18] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 22.

[19] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 5. Longman states: “A nation’s gross domestic product is literally the sum of its labour force times the average output per worker. Thus, a decline in the number of workers implies a decline in an economy’s growth potential…The European Commission…projects that Europe’s potential growth rate over the next fifty years will fall by 40 percent due to the shrinking size of the European work force.” Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004).41. He further elaborates as follows: “Exploding health and pension costs, along with a shrinking tax base, diminish resources available to households, government, and the private sector for investing in the next generation, even as the need for human capital formation increases. Another reason is rooted in the realities of the life cycle. It’s not just that most technological breakthroughs and entrepreneurial activity tend to come from people in their 20s and 30s…an ageing population will likely become increasingly risk averse….” Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 43.

Walter White: father, teacher, small business owner

21 July 2014 by Catherine Holdsworth in Business and finance, Entertainment

It’s coming up to a year since I signed up to Netflix, intending to terminate my subscription after the free trial had finished. Walter White, however, had other ideas for me. Vince Gilligan’s series, Breaking Bad, had not concluded and so I was stuck with Netflix until it had. Twelve months on, I’m still paying!

So what can we learn from the antihero Walter White about business strategy? Over five seasons, White built up his small meth business from a mobile home, to an underground hub of activity, eventually going mobile. White declared ‘I’m in the empire business’, but was this really as effective as his original small business? We watched Walt go from teacher, to meth cook, to car wash owner, then culminating as head of his so-called empire.

Even the greatest empires, however, must crumble. Walt’s ambition to get more money and power meant that he lost control of his company. Once the integrity and credibility of the company had been compromised (yes, even druglords can have integrity), Walt’s fall from grace was inevitable.

Even the greatest empires, however, must crumble. Walt’s ambition to get more money and power meant that he lost control of his company. Once the integrity and credibility of the company had been compromised (yes, even druglords can have integrity), Walt’s fall from grace was inevitable.

The success of Walt’s business was branding and efficiency. Well-planned cook sessions ensured that Walt and Jesse were efficient producers of the elusive blue meth. Even the smallest entrepreneurs can be successful by making their products unique to the market and easily identifiable when viewed alongside the goods of similar companies. Stand out from competitors by giving yourself an edge. Walt’s brand was not just the colour and purity of his product, it was his brand-name: Heisenberg; easily identifiable and synonymous with his product. Much like Walt delegated in his business (he was the cook, Jesse was the dealer) so you can optimise your profit margin by being the best at what you do.

Walt’s legitimate car wash business allowed for the shady meth business to flourish. Without advocating money-laundering, one can learn much from both businesses. Though it worked well to begin with, the growing meth empire was too much for the car wash to cover, as Walt’s wife Skyler struggled to launder the scale of the money that Walt was earning, it wasn’t long before both businesses folded. So what’s more important than an impossible-to-spend pile of money taking up valuable storage space, is integrity for both yourself and the business. Branching out too quickly could make your small business collapse like a house of cards.

Know your business, know what your customer needs and don’t let ambition overwhelm you.

Top 10 management models for your business: #4 Blue Ocean Strategy

16 July 2014 by Infinite Ideas in 100+ Management Models, Business and finance

by Fons Trompenaars and Piet Hein Coebergh, co-authors of 100+ Management Models.

Problem Statement

How can we create a long-term plan for sustained competitive advantage by focusing on new markets, without focusing on competition?

Essence

Kim and Mauborgne developed their Blue Ocean strategy in 2005, building on earlier

publications that also explored the insight that an organization should create new demand in an uncontested marketspace, or a ‘blue ocean’, where the competition is irrelevant. In blue oceans, organizations invent and capture new demand, and offer customers a leap in value while also streamlining costs. The central idea is to stop competing in overcrowded industries, so-called ‘red oceans’, where companies try to outperform rivals to grab bigger slices of existing demand. As the space gets increasingly crowded, profit and growth prospects shrink because products become commoditized. Ever more intense competition turns the water bloody. Blue Ocean strategies result in better profits, speedier growth and brand equity that lasts for decades while rivals scramble to catch up.

How to use the model:

The authors provide many examples of businesses that have created new markets (blue oceans) and present a model for crafting supporting strategies.

- Eliminate factors in your industry that no longer have value;

- Reduce factors that over-serve customers and increase cost structure for no gain;

- Raise factors that remove compromises buyers must make;

- Create factors that add new sources of value.

In addition, Kim and Mauborgne list a number of practical tools, methodologies and

frameworks for formulating and executing blue ocean strategies, attempting to make the creation of blue oceans a systematic and repeatable process. In their 2009 article ‘How Strategy Shapes Structure’, Kim and Mauborgne stress the importance of alignment across the value, profit and people propositions, regardless of whether one takes the structuralist (traditional competitive, Porter-like) or the reconstructionist (blue ocean) approach to strategy.

Results

Blue Ocean strategy should result in making the competition irrelevant. Therefore,

organizations need to avoid using the existing competition as a benchmark. Instead, make the competition irrelevant by creating a leap in value for both your organization and your customers. Another result should be the reduction of your costs while also offering customers more value. For example, Cirque du Soleil omitted costly elements of traditional circuses, such as animal acts and aisle concessions. Its reduced cost structure enabled it to provide sophisticated elements from theatre that appealed to adult audiences – such as themes, original scores and enchanting sets – all of which change from year to year.

Comments

The logic behind Blue Ocean strategy is counter-intuitive, since blue oceans seldom result from technological innovation. Often, the underlying technology already exists and blue ocean creators link it to what buyers value. Furthermore, organizations don’t have to venture into distant waters to create blue oceans. Most blue oceans are created from within, not beyond, the red oceans of existing industries. Incumbents often create blue oceans within their core businesses. A similar idea was put forward by Swedish management authors Jonas Ridderstråle and Kjell Nordström in their 1999 book Funky Business. Blue Ocean strategy is an inspiring way to look afresh at familiar environments with a view to finding a competitive edge. Unfortunately, most companies have marketing and strategy departments that look for benchmarks to be inspired by and copy rather than trying to be different.

Literature

Kim, W.C., Mauborgne, R. (1997) ‘Value Innovation – The Strategic Logic of High Growth’, Harvard Business Review, January/February, pp. 103–112.

Kim, W.C., Mauborgne, R. (2004) ‘Blue Ocean Strategy’, Harvard Business Review, January/February, pp. 71–79.

Kim, W.C., Mauborgne, R. (2009) ‘How Strategy Shapes Structure’, Harvard Business Review, September, pp. 72–80.

RoboFuture? Ten questions about machine intelligence

11 July 2014 by Infinite Ideas in Business and finance, Codebreaking our future

by Michael Lee, author of Codebreaking our future

[Originally published as a blog on the World Future Society website]

Ever since HG Wells wrote The War of the Worlds in 1897, various works of science fiction have speculated about the take-over of humanity by advanced robots or machines. Inventor and futurist Ray Kurzweil has gone several steps ahead of science fiction by working out an elaborate philosophy and pathway to a future governed by machine intelligence.

Kurzweil postulates that the Singularity will happen in 2045 when “the pace of technological change will be so rapid, its impact so deep, that human life will be irreversibly transformed” [Kurzweil, R (2005): 7]. It will represent, he claims, the “culmination of the merger of our biological thinking and existence with our technology…There will be no distinction, post-Singularity, between human and machine or between physical and virtual reality.” [Kurzweil, R (2005): 9] The non-biological intelligence created in the year of the Singularity, he states, will be one billion times more powerful than all human intelligence today [Kurzweil, R (2005): 136].

For computer scientist and science fiction author, Vernor Vinge, the core of the Singularity would be “the creation of greater-than-human intelligence” [More, M. & Vita-More, N (2013): 366] at which point all human rules will be thrown away in the face of an “exponential runaway beyond any hope of control” [More, M. & Vita-More, N (2013): 366]. After Singularity, Vinge and Kurzweil both proclaim, we’ll wake up in a radically new Post-human era.

I have several philosophical, logical, ethical, historical and futurological problems with the concept of the Singularity (which I will explore in future blogs) but today I simply want to adopt a common-sense approach. I want to ask 10 questions about machine intelligence. Readers can then answer each one as they see fit. The idea is to highlight the nature of machine intelligence compared to human consciousness.

While information technology has already attained unbelievable and revolutionary utility in today’s world, human intelligence, in my view, is far superior in virtually every facet to the intelligence within computer systems except for the processing, aggregating, calculating, storing and distribution of data at blindingly fast speeds. There have been several decades of worldwide research and development in the field of computers and so it is fair game to dig deep, at this juncture, as to the kind of intelligence which has actually been produced by computers in practice.

Here they are, then, ten questions to ask any man-made machine:

- Has machine intelligence ever independently produced an original idea, theory, philosophy or discovered any new principle or law of existence? This question concerns the capacity for sustained, original, creative thought.

- Has machine intelligence ever produced a unique, non-programmed story or created any imaginative literary work? This question relates to the power of imagination.

- Has a computer ever spontaneously said “I love you” and meant it? Q3 is about personal, real-time communication.

- Has a computer ever said “I’m sorry” and meant it? This question relates to empathy, the skills of listening and emotional intelligence in general.

- Has machine intelligence ever invented or coined a new word or term? Q5 concerns original linguistic talent.

- Has machine intelligence ever made an independent, non-programmed decision about how to act based on conscience? This question is about ethics and a sense of justice.

- Has a machine ever come up with a solution to a tricky social problem, solved a crime or adjudicated in a complex legal dispute? Q7 relates to the powers of deductive reasoning and lateral thinking.

- Has technology itself ever invented new technology, that is, have machines ever produced new types of machine no human had previously thought of? This question touches on the ability to be truly inventive.

- Has a machine ever had a religious or spiritual experience, an epiphany or eureka moment, said a non-programmed prayer, exercised faith or known awe and wonder? Q9 is about human spirituality.

- Has a machine ever made a spontaneously, personally motivated, non-programmed exchange with another being, whether some form of trade or extended social interaction? This question relates to the ability to engage in complex social, economic and political activity as a social being.

Aside from investigating the many technical and philosophical questions relating to the evolving interface between human and machine intelligence, these ten common-sense questions show it would be well-nigh impossible to mimic human consciousness and intelligence, let alone recreate, upload and surpass it, as proposed by Kurzweil.

Besides, do we really want to hand over control of civilization and human destiny to machinery?

Don’t we want to use, rather than become, technology?

Note: please feel free to send answers to any of these “ten questions to ask machines” to michael@futurology.co.za.

Acknowledgments

Kurzweil, R. 2005. The Singularity is Near – when humans transcend biology. London:Duckworth.

More, M. & Vita-More, N, ed. 2013. The Transhumanist Reader. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Climbing the ladder of chaos – why we all need some Littlefinger in us (ahem)

7 July 2014 by Rebecca in Business and finance, Entertainment, Game of Thrones on Business

Can we control the future? Maybe, says Tim Phillips, a better question is should we even try?

There’s a famous speech, one of my favourite bits, in Game of Thrones in which Petyr Baelish, the amoral political fixer known as Littlefinger, dismisses the historical texts as, “a story we agree to tell each other over and over, until we forget that it’s a lie.” When Lord Varys points out that the alternative is chaos, Littlefinger points out that chaos isn’t something to fear:

If the inhabitants of the seven kingdoms are fully occupied trying to avoid falling into a pit of chaos, the environment in which they live doesn’t help. When dead people can be reanimated, for example, which must be disorientating. ‘Winter is coming’, we are told at the beginning, which reminds inhabitants of the time when a previous winter lasted a generation. Why did it do that? Maybe it doesn’t matter much if there are undead people coming to kill you as a result.

If the inhabitants of the seven kingdoms are fully occupied trying to avoid falling into a pit of chaos, the environment in which they live doesn’t help. When dead people can be reanimated, for example, which must be disorientating. ‘Winter is coming’, we are told at the beginning, which reminds inhabitants of the time when a previous winter lasted a generation. Why did it do that? Maybe it doesn’t matter much if there are undead people coming to kill you as a result.

So Littlefinger has a point: when things change, old certainties become less valuable, less useful, no matter how comforting they are. Yet the idea that our societies and lives are in equilibrium is alluring for all of us.

We build it into the way we teach business, in which the forces of supply and demand balance to create stable prices and employment and growth. Yet, at the same time, we also know this isn’t really true. The economist Joseph Schumpeter was the first to identify a process he called ‘creative destruction’, in which innovation destroys the old world to create a better one. Real entrepreneurs don’t just tweak existing ideas, they rip them up and start again. If you do this successfully, you get your reward because you are in a field of one: but the risk of disaster is much greater. Schumpeter realised that disequilibrium is normal. We also now know that this applies in society, or to the weather.

It doesn’t even take an entrepreneur to create disequilibrium. In the UK, one in seven workers have been made redundant since the start of the financial crisis, which would have seemed inconceivable a decade ago. The chaotic nature of what economists call ‘the business cycle’ means that we might have a good idea of how secure our jobs will be next month, but no clear answer to the question if we ask about next year, and certainly no idea of the next 10 years.

We instinctively value continuity in our lives and our societies, and many of us react irrationally to disruptive change. In a recent experiment, the Royal Statistical Society took people who overestimated the problems of immigration, and confronted them with well-researched facts that contradicted their ideas. The people overwhelmingly decided that the statistics must be wrong.

We all think we wouldn’t do the same thing in our lives, but most of us react to sudden change by holding on to the stories we tell ourselves, even if they are not true. Not all of us can be a Littlefinger, climbing the ladder out of chaos, or a Schumpeterian entrepreneur, who creates the ladder in the first place.

We spend our lives in the understandable hope that chaos doesn’t come to our homes, families or workplaces. Insurance, savings and sandbags in the shed may help; but to flourish, rather than survive, we need to have a little bit of Littlefinger in us, and recognise that clinging exclusively to ‘the realm, or the gods, or love’ will eventually put us on the receiving end of some process of creative destruction.

Tim Phillips is author of Niccolo Machiavelli’s The Prince, Bertrand Russell’s The Conquest of Happiness, and Charles Mackay’s Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds.