Business and finance

Football business: transfer deadline day

1 September 2014 by Catherine Holdsworth in Business and finance, Football Business

It’s transfer deadline day. Now that the world cup is over, the Premiership Autumn season is beginning.We’ve already heard about Balotelli’s move to Liverpool, Sanchez to Arsenal and Diego Costa to Chelsea. The English teams’ injection of European talent will undoubtedly shake up the football season over the next few months.

Until midnight tonight, fans will be refreshing twitter and glued to Sky Sports News to keep up to date with the latest changes, panic buys and assess Harry Redknap’s coping techniques. Such is the importance of the premier league to the fans. Emotional, not to mention financial, investment in teams and payers is huge.

The transfer fees spent on these top players sound like monopoly money to the majority of us, but why are the sums involved so huge? In his new book, Football business, Tsjalle Van Der Burg looks back at the reasons transfer fees are so high, and why clubs are in such a rush to sell off their players before their contracts expire.

Jean-Marc Bosman was a player with Belgian club RC Liège. In 1990 his contract expired and he wanted to move to the French club Dunkerque. However, he was unable to do so because Liège demanded too high a transfer fee. Bosman took his club to court. The case eventually went to the European Court of Justice, the highest court of the EU. Bosman invoked the principle of free movement of workers, which had been part of European law since 1957. In 1995, after five years of legal struggle, the Court vindicated Bosman: it ruled that players whose contracts had expired could move clubs on free transfers. This ruling will remain in force as long as European law is not amended.

The ruling has not only affected out-of-contract players; it has also had a moderating effect on the transfer sums paid for players with ongoing contracts. The reason is that clubs feel pressure to sell a player at a relatively early stage, for fear that he will otherwise leave on a free transfer. To be clear: this is not to say that the total of all transfer fees has fallen since 1995. On the contrary, it has risen. But that is because all the clubs now have more money than they did in 1995. However, total transfer fees would have been higher still if there had been no Bosman ruling.

The ruling has ensured that the big clubs can more easily lure good players away from the small clubs. As a result, the most talented players tend to move to the big clubs at a younger age. The ruling hits the poor clubs hardest; they receive less money from transfers than would have been the case without the ruling. This makes it hard for those clubs to maintain the quality of their sides, because they need a lot of money to pay today’s high player wages. Sometimes clubs overcome the problem of the Bosman ruling with long-term contracts. But these can also work to their disadvantage: if a player fails to fulfil his promise his club may nevertheless have to continue paying his wages for years. All in all, the ruling has weakened the transfer system and it has added to the competitive inequality.

Since 1995 there have been some other, smaller changes in the transfer system as a result of pressure from the EU. For instance, the EU, FIFA and UEFA have agreed that the duration of a contract should be a maximum of five years. It has also been agreed that contracts have to be protected for a period of three years for players up to the age of twenty-eight, and two years for older players. Until now this rule has had little practical effect due to its vagueness; it is not clear exactly what the legal rights of club and player are when a player has served three years of a five-year contract, or two years if he is an older player.

However, it is possible that, in such cases, the maximum transfer fee will become equal to the salary the player would have earned in the remaining years of his contract. This will have a downward effect on transfer fees, and so football will become a bit less competitive still, thanks to the EU.

It is debatable whether the contracts involved are really worth what’s paid for them, and Van der Burg would argue that football has not necessarily been made more exciting or competitive as a result of the massive amounts of cash now spent by clubs. What is clear is that, come midnight tonight, in the final frenzy of buying and selling, there will be new and exciting players waiting to shake up the premiership and make for another thrilling season.

Top 10 management models for your business #7: Situational crisis communication theory, Timothy Coombs (1995)

27 August 2014 by Catherine Holdsworth in 100+ Management Models, Business and finance

by Fons Trompenaars and Piet Hein Coebergh, co-authors of 100+ Management Models.

Problem statement

How should an organization communicate during a crisis?

Essence

According to Timothy Coombs, crises are negative events that cause stakeholders to make ‘attributions’ (interpretations) about crisis responsibility, affecting how stakeholders interact with the organization. Attribution theory holds that people constantly look to find causes, or make attributions, for different events, especially if those events are negative or unexpected. In his situational crisis communication theory (SCCT), Coombs suggests that effective crisis response depends on the assessment of the situation and the related reputational threat.

To support this assessment, Coombs distinguishes three clusters of crises:

- Victim: Where the organization is a victim of the crisis (e.g. natural disasters, rumours) – minor reputational threat;

- Accident: Where the organizational actions leading to the crisis were unintentional(e.g. equipment or product failure, accusations from external stakeholders) – medium reputational threat;

- Intentional: Where the organization knowingly took inappropriate risk – major reputational threat.

Additionally, reputational threat is potentially ‘intensified’ (positively or negatively) by crisis history (were there similar crises in the past with this organization?) and prior relational reputation (how is the organization known for treating stakeholders?).

How to use the model

Once the levels of crisis responsibility and reputational threat have been determined,

SCCT builds on communications professor William L. Benoit’s image restoration model by identifying a limited set of primary crisis response strategies:

- Denial (attacking the accuser, denial of the story, scapegoating);

- Diminishment (offering excuses, justification of what happened);

- Rebuilding (compensation of victims, offering apologies, taking full responsibility).

A secondary, supporting crisis response strategy is bolstering, or reinforcing: reminding stakeholders about the good works of the organization and/or how the organization is a victim as well. Neither Benoit nor Coombs considers silence as a strategy, with Coombs stating that ‘Silence is too passive and allows others to control the crisis’ (Coombs and Holladay, 2012). Indeed, much has changed since 1882, when entrepreneur William Vanderbilt could say ‘The public be damned’.

For monitoring purposes, professor Marita Vos developed a crisis communications scorecard to measure clarity, environmental fit, consistency, responsiveness, effectiveness and efficiency of concern communications, marketing communications, internal communication and the organization of communications. Detailed information is available at www.crisiscommunication.fi.

Results

SCCT identifies as crisis outcomes: organizational reputation, effect (emotions of stakeholders, like sympathy or anger) and behavioural intentions (of stakeholders, like purchase intention or word of mouth). Coombs points out that the effectiveness of the crisis response is also influenced by how the organization managed the pre-crisis phase (prevention and preparation) and the post-crisis phase, (learning from mistakes and successes). Whereas the dynamics of social media limit the time for thinking a crisis response through, time can be won in the preparation phase, as social media offers various opportunities to see a crisis coming.

Comments

Similar to corporate apologia theory and image repair theory, SCCT has a strong focus on corporate reputation repair. In developing a crisis response strategy, there are factors not included in SCCT that might also be considered to determine reputational threat. Potentially influential factors might be the role of culture, the role of visual elements in crisis media coverage, or other factors that are recognized by attribution theory, contingency theory (built on the idea that there is no best way to organize a corporation) and complexity theory (dealing with the ‘black swans’, or uncertainty about the unknown unknowns).

As SCCT is a model for understanding crisis communication on a strategic level, it does not provide detailed guidelines on the tactics of crisis communication. As a general guideline, the advice of PR consultant and author Leonard Saffir applies: ‘Be quick with the facts, slow with the blame.’

Literature

Benoit, W.L. (1997) ‘Image Restoration Discourse and Crisis Communication’, Public Relations Review, 23:2, pp. 177–186.

Coombs, W.T., Holladay, S.J. (2012) The Handbook of Crisis Communication, Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell.

White, C.M. (2012) Social Media, Crisis Communication, and Emergency Management: Leveraging Web 2.0 Technologies, Boca Raton, Taylor & Francis.

New release: Football Business

27 August 2014 by Catherine Holdsworth in Book publishing, Business and finance, Football Business

Players’ whopping wages, ludicrous transfer fees, and escalating ticket prices frequently hit the headlines when it comes to football. But there is far more to football’s finances than this, claims Tsjalle van der Burg, author of Football business.

Football business will be available to buy from 1st September 2014, transfer deadline day. The book shows how the economics of European football have developed to the point where the structure of the business of football is now at odds with the game itself and the fans it was originally created for.

An economist at the University of Twente in the Netherlands and a football enthusiast, Van der Burg exposes the hidden face of football’s finances and shows how the economics of this beautiful game have gradually taken it out of the reach of enthusiasts and into the hands of entrepreneurs. In Football business, he unveils the key forces at play in today’s most followed sport and points an accusatory finger at commercialism and greed, which have come to shape the current nature of the game.

In a series of engaging and topical stories, van der Burg rattles the cage of football and gradually exposes the inequalities of the current system; he brings to light the weaknesses of UEFA’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules, takes a stand against pay TV and reveals how, in a global market for sponsorship and television rights, the competition amongst clubs is fiercer off the pitch than on it. His criticism of players’ inflated salaries is underpinned by solid economic principles, which expose the gap between their financial worth and their astronomical wages. At the centre of the book is Van der Burg’s desire for a redemption of the game; his call for a lowering of footballers’ pay and a redistribution of the surplus in the community is as much animated by philanthropy as by his passion for football.

Van der Burg’s plea for a prompt rectification of European football’s off the pitch rules takes centre stage in the latter part of the book. A ‘robust system of financial control’ to bring football back to its most honourable days must be introduced, argues van der Burg. While ‘many things are wrong with the EU’ he adds, ‘it’s the only body with the power to bring football back to the people.’ But whether the EU will be willing to revive football’s honour is still uncertain. ‘Will the fans walk alone’, asks the author? The answer, he suggests, depends very much on whether those in control are prepared to depart from their current path.

Dr Tsjalle van der Burg teaches economics at the University of Twente in the Netherlands. He has a special interest in popularizing economics and has published on economic subjects in national newspapers and spoken on radio and television. Van der Burg is a lifetime supporter of Feyenoord.

Breaking even or breaking bad: is your business the American Dream?

19 August 2014 by Catherine Holdsworth in Business and finance, Entertainment

The legend of the American Dream can be traced back as early as the first Europeans to settle the continent, recounting how they stepped off the Mayflower and started a new life in the Brave New World. The American Dream is what drove Europeans to board ships and make the perilous journey across the Atlantic in search of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Since the advent of the twentieth century, however, the American Dream has tended to represent the pursuit of wealth and capital, as portrayed in such classics as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. America, more than any other country represents capitalism through its large corporations, and companies aiming to stake their claim in the market.

The American Dream in the twenty-first century is promoted as something achievable by all, as TV shows, advertising and reams of self-help articles urge Americans forward, with the promise of wealth, success and happiness if only they strive hard enough. In the TV series Breaking Bad, Walter White’s small but successful business grew into an empire, spiralling dangerously out of control. In the beginning, Walt had clear financial goals: to pay his medical bills and ensure his family’s financial stability after his death. However, with his stock growing at an exponential rate, Walt’s greed and desire for more cost him dearly.

It’s all very well to have millions in the bank and a yacht to holiday on but the danger of this is that one loses touch with reality. The advantage of a small business is that it’s easier to stay true to the ethos of what made the company successful and maintain excellent customer relations – key to the longevity of a business. In an age where word-of-mouth is as good a recommendation as any, and reputations can be destroyed with a tweet, it is essential that small businesses maintain their integrity.

Take, for example, Amazon, a ‘Fat Cat’ company that creates trouble for even moderately sized companies, such as Hachette. With the companies reaching a stalemate, their disagreement has had a knock-on effect on customers, who are now unable to buy books by the publisher on Amazon’s site. There are parallels between Amazon’s relatively swift rise from small bookseller to world-beating supplier of everything, and the success of Walt and Jesse’s meth business. First the Breaking Bad entrepreneurs made other dealers and suppliers redundant by supplying a better product and better service – Amazon built its business on great service and the best prices. Moving into bigger premises with an effective distribution model brought Walt and Jesse wealth but also enemies; once Walt and Jesse were ‘on the map’, they were hunted, not just by the police, but by rival dealers, desperate for blood. Amazon is still loved by customers, but from the other end of the supply chain there are many who despise its approach to business and would be glad to see the company brought low. Whether their dreams come true remains to be seen but if you do find yourself at the helm of a successful business you’d be wise to remember that reputation is all-important.

Essentially, Walt is a product of his environment. In a country reliant for its survival on commerce and the pursuit of wealth, Walt was faced with thousands of dollars worth of debt due to a low income and expensive health care; he would not have been in such a predicament had he lived in Canada or the UK. Thus his entrepreneurial spirit was ignited and he had no choice but to make quick and easy money. Nevertheless, as many small businesses have found out, quick money is not necessarily the key to a flourishing business and in that cut-throat, boom or bust world, burning out is a real risk. Though Amazon is a leader in the field of selling anything, offering a virtual department store at you fingertips, there is a growing backlash against the company with some consumers going out of their way to buy their products from somewhere else. Whatever the American Dream means to you, make sure you business is not compromised.

The Premier League season 2014–2015 kicks off

15 August 2014 by Rebecca in Business and finance, Football Business

Well, after what seems like an eternity with not even a mention of football, the new Premier League season is about to begin. So are you excited, wondering how your team will fare this year? Looking forward to some flashes of goal-scoring genius? Wondering who the season’s new star will be (perhaps it’s the manager – or perhaps not)? More importantly – have you been saving up?

As football fans are all too well aware the price of following the world’s favourite sport can take its toll – some have even started to protest the prices of attending a match. When you look at some of the costs assiociated with supporting football these days you can start to see why these fans are angry. Here are just a few examples of current Premier League prices:

- A season ticket for last year’s cup champions Arsenal, the Premier League’s most expensive, will cost you a minimum of £1,014. Which makes last year’s league champions seem like a bargain – a season ticket at City will only set you back £299.

- A ticket to Manchester United’s match versus Swansea at Old Trafford tomorrow (could you get your hands on a legitimate one) will set you back between £31 and £53.

- Should attending matches be too rich for your blood you could always subscribe to Sky Sports for an extra (yes, on top of your basic subscription) £24.50/month. But don’t forget you’ll need an account with BT too if you want to watch all the Premier League matches, as many of the top games this season will be live on BT Sport.

- A shirt for any of the big five costs £49.99. If you want one for your offspring too that’s another £35–40 per child.

But OK, it’s 2014 and the prices of everything have gone up in our lifetimes; that’s the way commerce moves. Perhaps it doesn’t matter that with your season ticket to Arsenal, a new shirt and attendance at all the away games you’re going to be spending in the region of at least £2000, if you get £2000-worth of enjoyment from it. But as author Tsjalle van der Burg points out in his new book, Football business, the cost of football has risen out of line with the economy as a whole. He thinks it’s unlikely that the enjoyment of fans has risen in line with the costs of being a fan.

In fact the way football is run now it is likely that it has become less enjoyable for the fans, largely due to what Van der Burg calls ‘competitive inequality’. In simple terms this means that the wealthier clubs (those owned by oligarchs and sheikhs) can afford better players, making them more likely to win tournaments and leagues. Consistently winning teams get more supporters and sell more tickets, get more promotional opportunities and make more money from the TV rights to games. So the rich become richer. If you support a less wealthy club, watching matches against the wealthier clubs can be frustrating as you know you have very little chance of winning. But this inequality can also make games less enjoyable for the fans of wealthier clubs – if you know you have very little chance of losing, a lot of the excitement of winning is taken away. As Van der Burg points out, enjoyment can’t be measured scientifically but he notes:

“In football, the quality of the basic product – football matches – has not improved over the years. Barcelona–Real Madrid is no more enjoyable or exciting today than it was in the past. Lionel Messi does not entertain the average Barcelona fan more than Johan Cruijff used to. And in all competitions, fewer goals are scored now. It’s a safe bet that in the next final of the Champions League there will not be ten goals in 90 minutes, as there were in the 1960 European Cup final. One of the reasons may be that current coaches put results ahead of entertainment, precisely because of the enormous amounts of money at stake.”

Van der Burg is an economist so he has tried to work out the problem using economic calculations. He asks if the sport would be more enjoyable if all clubs had the same chance of winning. You might think the simple and obvious answer is ‘Yes’ but as Van der Burg points out, if you take it down to bare statistics it’s not that clear cut – after all Liverpool have far more fans than Swansea so when Swansea beat Liverpool the enjoyment is experienced by a smaller proportion of fans. But:

“If Swansea were to win the title next year, the pleasure of the average fan of the league champion would possibly reach an all-time high. In addition, people who have sympathy for the underdog would also be pleased. A Swansea title would show that, however hopeless a situation may seem, and however life turns against you, hope is always justified. This will also make the fans of other clubs feel better during the next season, since much of their pleasure is based on hopes and expectations. Indeed, this is what [Major League Basebell promoter] Bill Veeck taught us long ago: sports clubs produce dreams. And to enable fans to dream, it would help if clubs like Swansea had some chance of winning the title one day.”

One thing is certain – football has more fans than ever worldwide. When the season kicks off at Old Trafford at 12.45 tomorrow excitement will be high not just in Swansea and wherever it is that United’s fans live but as far afield as Asia and South America. If we could find a way to keep that feeling going for all fans all season we’d be on to a winner.

Do you think football has become too expensive? Have you lost your enjoyment of the game as prices have risen or do you think it has become more exciting and enjoyable? Let us know what you think by filling in the comment box below or contacting us via Facebook or Twitter using the social media sharing buttons.

Top 10 management models for your business #6: Social media ROI pyramid

13 August 2014 by Infinite Ideas in 100+ Management Models, Business and finance

Fons Trompenaars and Piet Hein Coebergh, co-authors of 100+ Management Models.

Problem statement

How can one measure the return on investment (ROI) of social media?

Essence

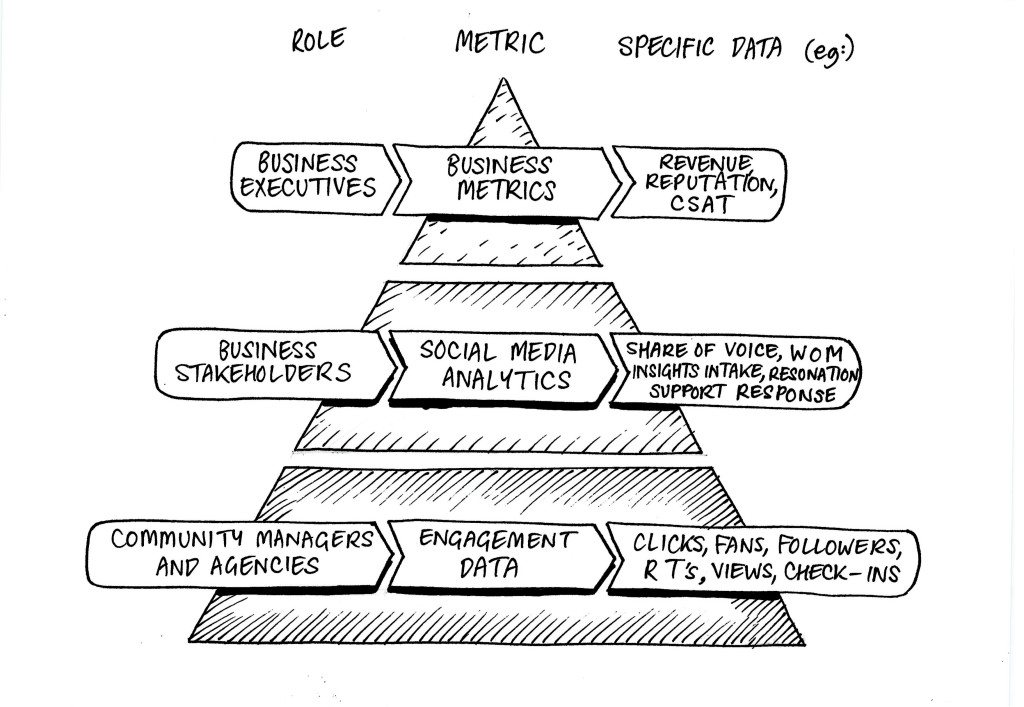

Return on investment (ROI) is a key concept in business, describing when an investment will be gained back. For investments in social media, Jeremiah Owyang, management consultant at Altimeter, developed a hierarchy of metrics, depicted above, to merge various forms of metrics for social media, serving various stakeholders in different roles. This model attempts to fulfil the need of an increasing number of organizations that find it difficult to define critical success factors and key performance indicators for online communications in general and social media in particular.

Owyang proposes distinguishing different, but related, metrics for different layers in an organization:

- Business metrics, for executives (and ‘everyone else who supports them’), summarizing the social media analytics;

- Social media analytics, for the managers and employees who are strongly engaged in social media, focusing on how social media impacts business;

- Engagement data, for community managers and communications agencies, measuring the social footprint in detail (e.g. in clicks, followers, likes, retweets, views, etc.).

How to use the model

Owyang proposes five steps to start using the ROI Pyramid:

- Start with a business goal in mind: expect significant challenges to occur if your social media efforts don’t have a business goal. It’s easy to spot when this happens, as the goal will be getting ‘more fans and followers’ rather than moving the business needle forward.

- Give the right data to the right roles: not all roles require the same types of data; be sure to give the right type of data to the right segment. While all the formulae of the pyramid should be accessible by the corporation, understand the viewpoints needed from each vantage point.

- Tailor the frequency and quantity of data along pyramid tiers: recognize that executives need reports less frequently than the deployment teams, hence their size on the pyramid. Also, there is more data needed at the bottom tiers than at the top; remember the top tiers are roll-up formulae from bottom tiers.

- Customize formulae: as long as there are no standards in measuring social media, there is no need to wait for them.

- Benchmark over time and cascade to all layers of the organization. Note that the specific numbers aren’t as important as the trend lines over time.

In addition, Owyang found that organizations apply ‘six ways of measuring the revenue impact of social media’, of which three are top-down: anecdotes, correlations and multivariate testing. The other three are bottom-up: measuring the ‘clicks’ (see also under ‘engagement data’ above), using integrated software and measuring e-commerce.

Results

Applying the model may result in developing an overall dashboard for the organization to monitor progress of a company’s conversation strategy, or it can be used to help define which metrics need further refinement and how they connect with other metrics (as, for instance, used in a balanced scorecard) that measure success in corporate communications.

Comments

Measuring the effect of communications has been a challenge for as long as communications have been studied. John Wanamaker, a pioneer of marketing in the nineteenth century, said: ‘Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is, I don’t know which half.’ Some critics argue that science hasn’t made much improvement since. Especially in online communications, trial and error is inevitable in making progress along the new frontiers of global communications. Measuring the plans and results will at least contribute to learning from mistakes and, at best, guide the organization into the envisioned future.

Literature

Blanchard, O. (2011) Social Media ROI: Managing and Measuring Social Media Efforts in your Organization, Boston, Pearson Education.

Broom, D., McCann, M., Bromby, M.C., Barlow, A. (2011) Return on Investment: What Literature Exists on the Use of Social Media and ROI? Available online at Social Science Research Network.

Kelly, N. (2013) How to Measure Social Media: A Step-by-Step Guide to Developing and Assessing Social Media ROI, Boston, Pearson Education.