100+ Management Models

Top 10 management models for your business #7: Situational crisis communication theory, Timothy Coombs (1995)

27 August 2014 by Catherine Holdsworth in 100+ Management Models, Business and finance

by Fons Trompenaars and Piet Hein Coebergh, co-authors of 100+ Management Models.

Problem statement

How should an organization communicate during a crisis?

Essence

According to Timothy Coombs, crises are negative events that cause stakeholders to make ‘attributions’ (interpretations) about crisis responsibility, affecting how stakeholders interact with the organization. Attribution theory holds that people constantly look to find causes, or make attributions, for different events, especially if those events are negative or unexpected. In his situational crisis communication theory (SCCT), Coombs suggests that effective crisis response depends on the assessment of the situation and the related reputational threat.

To support this assessment, Coombs distinguishes three clusters of crises:

- Victim: Where the organization is a victim of the crisis (e.g. natural disasters, rumours) – minor reputational threat;

- Accident: Where the organizational actions leading to the crisis were unintentional(e.g. equipment or product failure, accusations from external stakeholders) – medium reputational threat;

- Intentional: Where the organization knowingly took inappropriate risk – major reputational threat.

Additionally, reputational threat is potentially ‘intensified’ (positively or negatively) by crisis history (were there similar crises in the past with this organization?) and prior relational reputation (how is the organization known for treating stakeholders?).

How to use the model

Once the levels of crisis responsibility and reputational threat have been determined,

SCCT builds on communications professor William L. Benoit’s image restoration model by identifying a limited set of primary crisis response strategies:

- Denial (attacking the accuser, denial of the story, scapegoating);

- Diminishment (offering excuses, justification of what happened);

- Rebuilding (compensation of victims, offering apologies, taking full responsibility).

A secondary, supporting crisis response strategy is bolstering, or reinforcing: reminding stakeholders about the good works of the organization and/or how the organization is a victim as well. Neither Benoit nor Coombs considers silence as a strategy, with Coombs stating that ‘Silence is too passive and allows others to control the crisis’ (Coombs and Holladay, 2012). Indeed, much has changed since 1882, when entrepreneur William Vanderbilt could say ‘The public be damned’.

For monitoring purposes, professor Marita Vos developed a crisis communications scorecard to measure clarity, environmental fit, consistency, responsiveness, effectiveness and efficiency of concern communications, marketing communications, internal communication and the organization of communications. Detailed information is available at www.crisiscommunication.fi.

Results

SCCT identifies as crisis outcomes: organizational reputation, effect (emotions of stakeholders, like sympathy or anger) and behavioural intentions (of stakeholders, like purchase intention or word of mouth). Coombs points out that the effectiveness of the crisis response is also influenced by how the organization managed the pre-crisis phase (prevention and preparation) and the post-crisis phase, (learning from mistakes and successes). Whereas the dynamics of social media limit the time for thinking a crisis response through, time can be won in the preparation phase, as social media offers various opportunities to see a crisis coming.

Comments

Similar to corporate apologia theory and image repair theory, SCCT has a strong focus on corporate reputation repair. In developing a crisis response strategy, there are factors not included in SCCT that might also be considered to determine reputational threat. Potentially influential factors might be the role of culture, the role of visual elements in crisis media coverage, or other factors that are recognized by attribution theory, contingency theory (built on the idea that there is no best way to organize a corporation) and complexity theory (dealing with the ‘black swans’, or uncertainty about the unknown unknowns).

As SCCT is a model for understanding crisis communication on a strategic level, it does not provide detailed guidelines on the tactics of crisis communication. As a general guideline, the advice of PR consultant and author Leonard Saffir applies: ‘Be quick with the facts, slow with the blame.’

Literature

Benoit, W.L. (1997) ‘Image Restoration Discourse and Crisis Communication’, Public Relations Review, 23:2, pp. 177–186.

Coombs, W.T., Holladay, S.J. (2012) The Handbook of Crisis Communication, Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell.

White, C.M. (2012) Social Media, Crisis Communication, and Emergency Management: Leveraging Web 2.0 Technologies, Boca Raton, Taylor & Francis.

Top 10 management models for your business #6: Social media ROI pyramid

13 August 2014 by Infinite Ideas in 100+ Management Models, Business and finance

Fons Trompenaars and Piet Hein Coebergh, co-authors of 100+ Management Models.

Problem statement

How can one measure the return on investment (ROI) of social media?

Essence

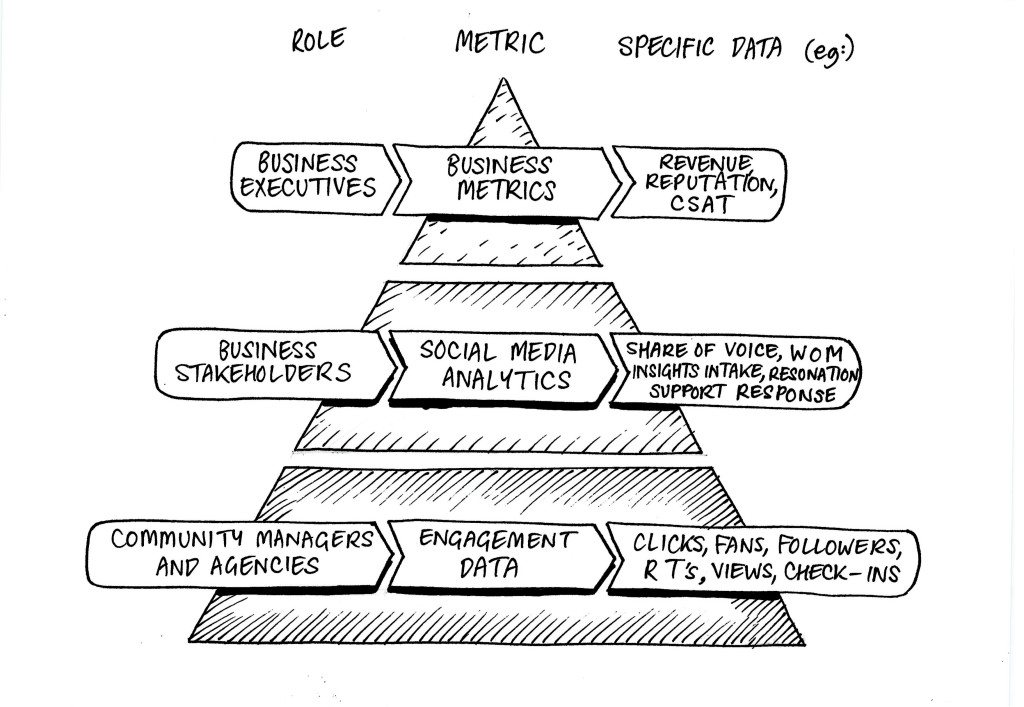

Return on investment (ROI) is a key concept in business, describing when an investment will be gained back. For investments in social media, Jeremiah Owyang, management consultant at Altimeter, developed a hierarchy of metrics, depicted above, to merge various forms of metrics for social media, serving various stakeholders in different roles. This model attempts to fulfil the need of an increasing number of organizations that find it difficult to define critical success factors and key performance indicators for online communications in general and social media in particular.

Owyang proposes distinguishing different, but related, metrics for different layers in an organization:

- Business metrics, for executives (and ‘everyone else who supports them’), summarizing the social media analytics;

- Social media analytics, for the managers and employees who are strongly engaged in social media, focusing on how social media impacts business;

- Engagement data, for community managers and communications agencies, measuring the social footprint in detail (e.g. in clicks, followers, likes, retweets, views, etc.).

How to use the model

Owyang proposes five steps to start using the ROI Pyramid:

- Start with a business goal in mind: expect significant challenges to occur if your social media efforts don’t have a business goal. It’s easy to spot when this happens, as the goal will be getting ‘more fans and followers’ rather than moving the business needle forward.

- Give the right data to the right roles: not all roles require the same types of data; be sure to give the right type of data to the right segment. While all the formulae of the pyramid should be accessible by the corporation, understand the viewpoints needed from each vantage point.

- Tailor the frequency and quantity of data along pyramid tiers: recognize that executives need reports less frequently than the deployment teams, hence their size on the pyramid. Also, there is more data needed at the bottom tiers than at the top; remember the top tiers are roll-up formulae from bottom tiers.

- Customize formulae: as long as there are no standards in measuring social media, there is no need to wait for them.

- Benchmark over time and cascade to all layers of the organization. Note that the specific numbers aren’t as important as the trend lines over time.

In addition, Owyang found that organizations apply ‘six ways of measuring the revenue impact of social media’, of which three are top-down: anecdotes, correlations and multivariate testing. The other three are bottom-up: measuring the ‘clicks’ (see also under ‘engagement data’ above), using integrated software and measuring e-commerce.

Results

Applying the model may result in developing an overall dashboard for the organization to monitor progress of a company’s conversation strategy, or it can be used to help define which metrics need further refinement and how they connect with other metrics (as, for instance, used in a balanced scorecard) that measure success in corporate communications.

Comments

Measuring the effect of communications has been a challenge for as long as communications have been studied. John Wanamaker, a pioneer of marketing in the nineteenth century, said: ‘Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is, I don’t know which half.’ Some critics argue that science hasn’t made much improvement since. Especially in online communications, trial and error is inevitable in making progress along the new frontiers of global communications. Measuring the plans and results will at least contribute to learning from mistakes and, at best, guide the organization into the envisioned future.

Literature

Blanchard, O. (2011) Social Media ROI: Managing and Measuring Social Media Efforts in your Organization, Boston, Pearson Education.

Broom, D., McCann, M., Bromby, M.C., Barlow, A. (2011) Return on Investment: What Literature Exists on the Use of Social Media and ROI? Available online at Social Science Research Network.

Kelly, N. (2013) How to Measure Social Media: A Step-by-Step Guide to Developing and Assessing Social Media ROI, Boston, Pearson Education.

Top 10 management models for your business #5: six stages of social business transformation

30 July 2014 by Infinite Ideas in 100+ Management Models, Business and finance

Fons Trompenaars and Piet Hein Coebergh, co-authors of 100+ Management Models.

Problem Statement

How can organizations optimize engagement with their target audience through social media?

Essence

Charlene Li and Brian Solis, consultants and authors on social media and digital marketing, have developed a leading body of knowledge on how organizations can deal with the rising importance of transparency and engagement. Their model builds on the ideas of Groundswell (Li and Bernoff, 2008), describing how people increasingly connect with each other to be informed, rather than listening to organizations. The book describes how companies are becoming less able to control customers’ attitudes through market research, customer service and advertising. Instead, customers increasingly control the conversation by using new media to communicate about products and companies. Li and Solis observe that organizations connect with customers by taking the following steps:

- Planning – ‘Listen and learn’: Ensure commitment to get the business social.

- Presence – ‘Stake our claim’: Evolution from planning to action, establishing a formal and informed presence in social media;

- Engagement – ‘Dialogue deepens relationships’: Commitment where social media is seen as a critical element in relationship-building;

- Formalized – ‘Organize for scale’: A formalized approach focuses on three key activities: establishing an executive sponsor, creating a centre of excellence and establishing organization-wide governance;

- Strategic – ‘Become a social business’: Social media initiatives gain visibility and real business impact.

- Converged – ‘Business to social’: Having cross-functional and executive support, social business strategies start to weave into the fabric of an evolving organization.

How to use the Model

The model can serve as a roadmap for organizations to improve their engagement with stakeholders, especially through social media. A model to measure current engagement of an organization with its target audience is Li’s Social Technographics Ladder (Li and Bernoff, 2008). The ladder identifies people according to how they use social technologies, classified as creators, critics, collectors, joiners, spectators and inactives. Taken together, these groups make up the ecosystem that forms the groundswell. Each step on the ladder represents a group of consumers more involved in the groundswell than the previous steps. To join the group on a step, a consumer need only participate in one of the listed activities. Steven van Belleghem, from Vlerick Business School, has developed a three-step approach to setting up and managing a conversation on any level of the Technographics Ladder: observe the conversation you perceive as relevant as an organization, facilitate the conversation you want to create and join the conversation as a peer.

Results

Implementing the model as a roadmap towards more social engagement requires leadership in managing this change process. The authors of Groundswell suggest the POST approach for change, working with people (assess social activities of customers), objectives (decide what you want to accomplish), strategy (plan for how relationships with customers will change) and technology (decide which social technologies to use).

Comments

The impact of the Internet on society in general, and of social media in particular, has not created a paradigm shift in social science, as yet. In academia, the information revolution and ongoing digitization is mostly being explained by classic models, of which the most powerful are included in this book. Competing with these classics is a burgeoning variety of authors and consultants who publish all sorts of new models, mainly through media where displaying academic evidence is considered of low importance. The books of Li and Solis may not represent the state of the art in academia, but they do offer research-based, new, practical and appealing approaches in defining digital marketing.

Literature

Duhé, S. ed. (2012) New Media and Public Relations, 2nd Ed., New York, Peter Lang

Publishing.

Li, C., Bernoff, J. (2011) Groundswell, expanded and revised edition: Winning in a World

Transformed by Social Technologies, Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

Solis, B. (2011) Engage! The Complete Guide for Brands and Businesses to Build, Cultivate, and

Measure Success in the New Web, Hoboken, John Wiley.

Top 10 management models for your business: #4 Blue Ocean Strategy

16 July 2014 by Infinite Ideas in 100+ Management Models, Business and finance

by Fons Trompenaars and Piet Hein Coebergh, co-authors of 100+ Management Models.

Problem Statement

How can we create a long-term plan for sustained competitive advantage by focusing on new markets, without focusing on competition?

Essence

Kim and Mauborgne developed their Blue Ocean strategy in 2005, building on earlier

publications that also explored the insight that an organization should create new demand in an uncontested marketspace, or a ‘blue ocean’, where the competition is irrelevant. In blue oceans, organizations invent and capture new demand, and offer customers a leap in value while also streamlining costs. The central idea is to stop competing in overcrowded industries, so-called ‘red oceans’, where companies try to outperform rivals to grab bigger slices of existing demand. As the space gets increasingly crowded, profit and growth prospects shrink because products become commoditized. Ever more intense competition turns the water bloody. Blue Ocean strategies result in better profits, speedier growth and brand equity that lasts for decades while rivals scramble to catch up.

How to use the model:

The authors provide many examples of businesses that have created new markets (blue oceans) and present a model for crafting supporting strategies.

- Eliminate factors in your industry that no longer have value;

- Reduce factors that over-serve customers and increase cost structure for no gain;

- Raise factors that remove compromises buyers must make;

- Create factors that add new sources of value.

In addition, Kim and Mauborgne list a number of practical tools, methodologies and

frameworks for formulating and executing blue ocean strategies, attempting to make the creation of blue oceans a systematic and repeatable process. In their 2009 article ‘How Strategy Shapes Structure’, Kim and Mauborgne stress the importance of alignment across the value, profit and people propositions, regardless of whether one takes the structuralist (traditional competitive, Porter-like) or the reconstructionist (blue ocean) approach to strategy.

Results

Blue Ocean strategy should result in making the competition irrelevant. Therefore,

organizations need to avoid using the existing competition as a benchmark. Instead, make the competition irrelevant by creating a leap in value for both your organization and your customers. Another result should be the reduction of your costs while also offering customers more value. For example, Cirque du Soleil omitted costly elements of traditional circuses, such as animal acts and aisle concessions. Its reduced cost structure enabled it to provide sophisticated elements from theatre that appealed to adult audiences – such as themes, original scores and enchanting sets – all of which change from year to year.

Comments

The logic behind Blue Ocean strategy is counter-intuitive, since blue oceans seldom result from technological innovation. Often, the underlying technology already exists and blue ocean creators link it to what buyers value. Furthermore, organizations don’t have to venture into distant waters to create blue oceans. Most blue oceans are created from within, not beyond, the red oceans of existing industries. Incumbents often create blue oceans within their core businesses. A similar idea was put forward by Swedish management authors Jonas Ridderstråle and Kjell Nordström in their 1999 book Funky Business. Blue Ocean strategy is an inspiring way to look afresh at familiar environments with a view to finding a competitive edge. Unfortunately, most companies have marketing and strategy departments that look for benchmarks to be inspired by and copy rather than trying to be different.

Literature

Kim, W.C., Mauborgne, R. (1997) ‘Value Innovation – The Strategic Logic of High Growth’, Harvard Business Review, January/February, pp. 103–112.

Kim, W.C., Mauborgne, R. (2004) ‘Blue Ocean Strategy’, Harvard Business Review, January/February, pp. 71–79.

Kim, W.C., Mauborgne, R. (2009) ‘How Strategy Shapes Structure’, Harvard Business Review, September, pp. 72–80.

Top 10 management models for your business: #3 Reverse innovation

2 July 2014 by Infinite Ideas in 100+ Management Models, Business and finance

by Fons Trompenaars and Piet Hein Coebergh, co-authors of 100+ Management Models.

Problem Statement

How can reverse innovation create growth?

Essence

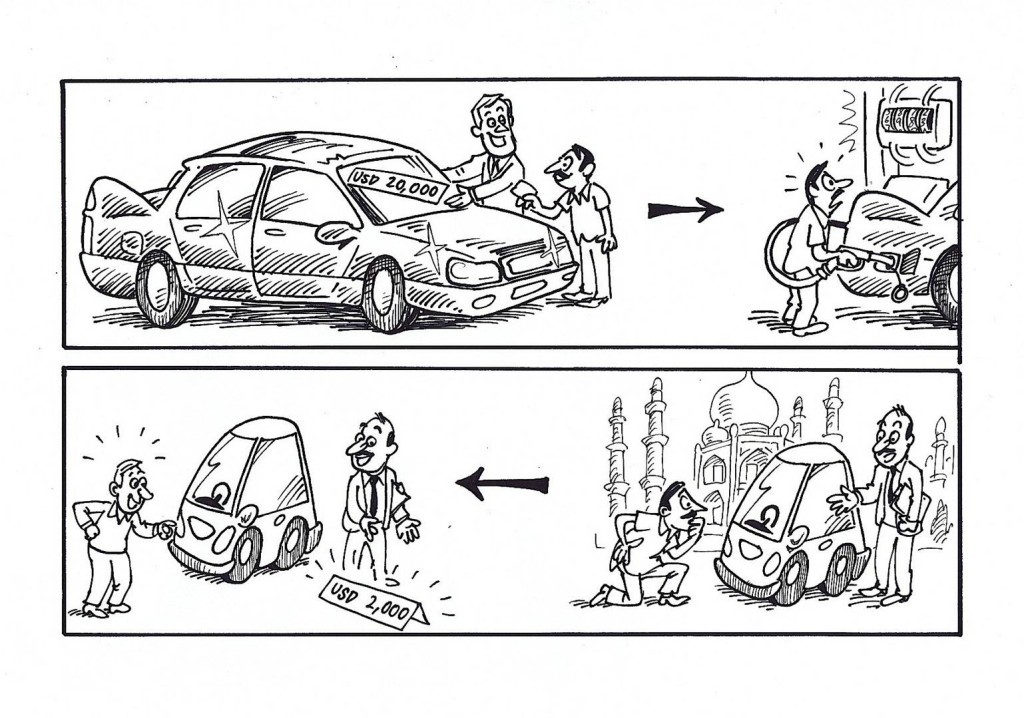

Vijay Govindarajan claims that the need and eagerness in emerging markets for sustainable growth creates an environment for innovation that is superior to the environment in more affluent countries. Govindarajan observes the following evolution: from globalization (richer countries that export what they use themselves) came glocalization (adaption to local needs on a global scale), followed by local innovation (emerging markets increasingly innovate themselves) which is making way for reverse innovation (emerging markets dominate innovation).

Reverse innovation is also called trickle-up innovation or frugal innovation. Govindarajan’s approach builds on Christensen’s theory of how innovation can be disruptive and C.K. Prahalad’s notion that there is a fortune to be made at the bottom of the social pyramid. Govindarajan served as the first professor-in-residence and chief innovation consultant at General Electric, some of the stories that illustrate reverse innovation were developed there, and supported by CEO Jeff Immelt.

How to use the model:

Govindarajan and Trimble’s Reverse Innovation Playbook (2012), covers nine rules ‘that will guide your innovation efforts’, in three categories, that can be summarized as follows:

- Strategy: To grow in emerging markets, innovate, not simply export; grow from innovations in emerging market to other emerging markets; beware of small but fast growing companies in emerging markets.

- Global organization: Move resources to where growth is; create a reverse innovation mindset; focus in these markets on growth metrics.

- Project organization: Stimulate an entrepreneurial ‘start-up’ spirit; leverage resources through partnerships; resolve critical unknowns quickly and inexpensively.

In addition, the Reverse Innovation Toolkit (2012) provides several practical diagnostics and templates to move reverse innovation forward in a company.

Results

Working with the Reverse Innovation Playbook and the Reverse Innovation Toolkit helps creative thinking about unconventional ways to innovate and grow. Evidence that supports this reverse-thinking model is mainly based on how multinational companies operate.

Comments

Like C.K. Prahalad’s theory of how a fortune can be made at the bottom of the pyramid, Govindarajan’s model has received criticism that the theory is not very specific in its approach and that there are only a few showcase examples, in a couple of big companies, to prove the concept, mainly from India and China. In addition, it is not completely unheard of for innovations from emerging markets to become successful, even in richer countries. That does not reduce the challenge that remains for rich countries of finding new ways to grow; in any scenario, this will increasingly be done with the emerging economies. Govindarajan presents a roadmap that at least has the power to take a radically different look at how most (Western) countries do business.

Literature

Govindarajan, V., Trimble, C. (2012) Reverse Innovation: Create Far from Home, Win Everywhere, Boston, Harvard Business Press.

Immelt, J.R., Govindarajan, V., Trimble, C. (2009) How GE is disrupting itself, Harvard Business Review, 87.10, pp. 56–65.

Mahbubani, K. (2013) The Great Convergence: Asia, the West, and the Logic of One World, New York, Perseus.

Top 10 management models for your business: #2 Multiple stakeholder sustainabilty

18 June 2014 by Infinite Ideas in 100+ Management Models, Business and finance

by Fons Trompenaars and Piet Hein Coebergh, co-authors of 100+ Management Models.

Problem Statement

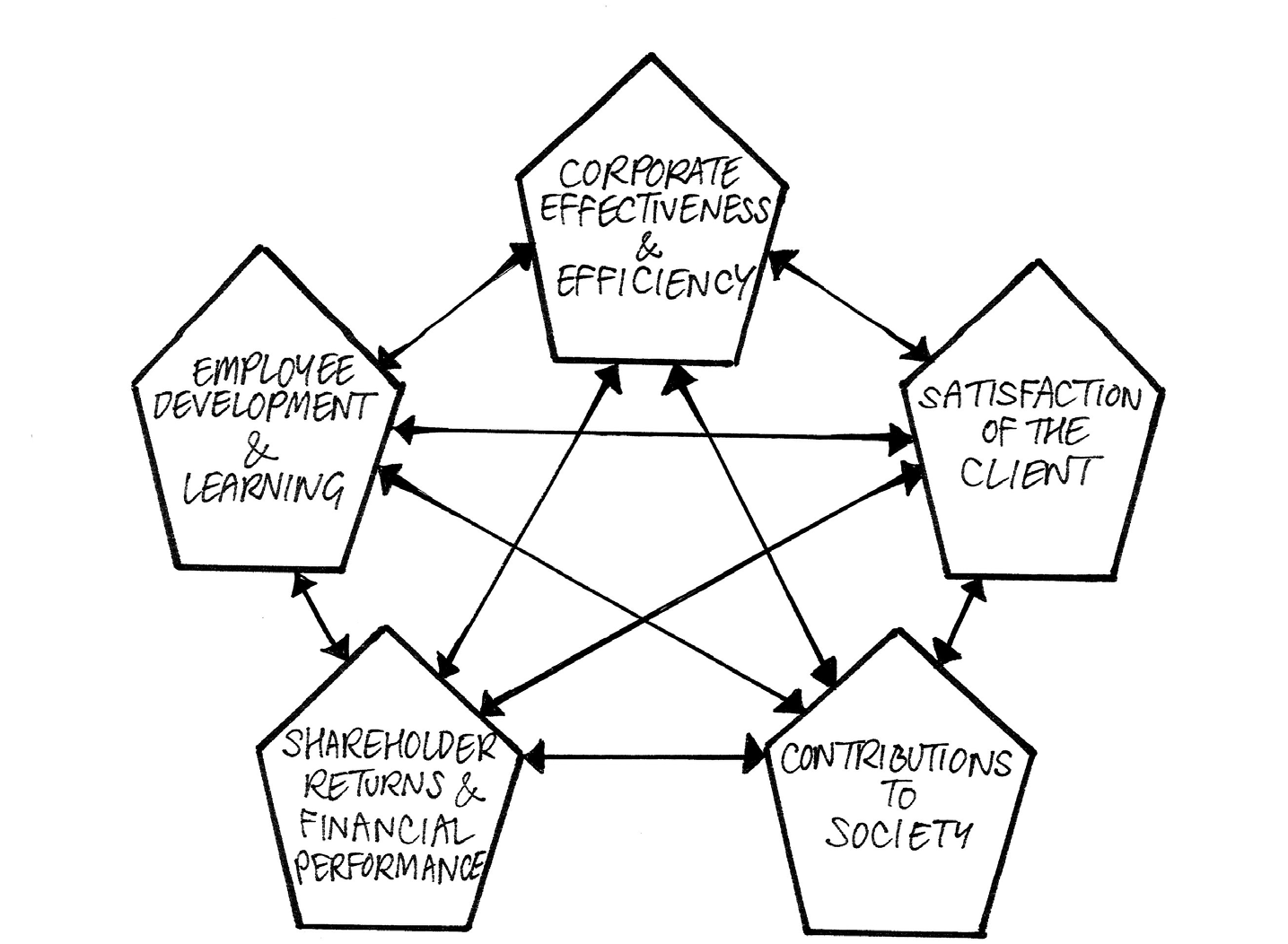

How can I assess the most significant organizational dilemmas resulting from conflicting stakeholder demands and also assess organizational priorities to create sustainable performance?

Essence

Organizational sustainability is not limited to the fashionable environmental factors such as emissions, green energy, saving scarce resources, corporate social responsibility, et cetera. The future strength of an organization depends on the way leadership and management deal with the tensions between the five major entities facing any organization: efficiency of business processes, people, clients, shareholders and society. The manner in which these tensions are addressed and resolved determines the future strength and opportunities of an organization. This model proposes that sustainability can be defined as the degree to which an organization is capable of creating long-term wealth by reconciling its most important (‘golden’) dilemmas, created between these five components. From this, professors and consultants Fons Trompenaars and Peter Woolliams have identified ten dimensions

Model 7: Multiple ultiple stakeholder stakeholder sustainability sustainability sustainability , Fons Trompenars and Peter Woliams Woliams Woliams (2010)

57

consisting of dilemmas formed from these five components because each one competes with the other four.

How to use the model:

The authors have developed a sustainability scan to use when making a diagnosis. This scan reveals:

- The major dilemmas and how people perceive the organization’s position in relation to these dilemmas.

- The corporate culture of an organization and their openness to the reconciliation of the major dilemmas.

- The competence of its leadership to reconcile these dilemmas. After the diagnosis the organization can move on to reconciling the major dilemmas that lead to sustainable performance. To this end, the authors developed a dilemma reconciliation process.

Results

To achieve sustainable success, organizations need to integrate the competing demands of their key stakeholders: operational processes, employees, clients, shareholders and society. By diagnosing and connecting different viewpoints and values their research and consulting practice results in a better understanding of:

ll. The key challenges the organization faces with its various stakeholders and how to prioritize them.

ll. The extent to which leadership and management are capable of addressing the organizational dilemmas.

ll. The personal values of employees and their alignment with organizational values.

These results help an organization define a corporate strategy in which crucial dilemmas are reconciled and ensure that the company’s leadership is capable of executing the strategy sustainably. It does so while specifically addresing the company’s wealth creating processes before the results show up in financial reports. It attempts to anticipate what the corporate financial performance will be, some six months to three years in the future, as the financial effects of dilemma reconciliation are budgeted.

Comments

The sustainability scan reconciles the key dilemmas that corporations face today and tomorrow. It takes a unique approach to making strategic decisions that are tough as well as inevitable with the goal of realizing a profitable and sustainable corporate future. Consulting firm Trompenaars-Hampden Turner offers an elaborate set of tools, of which a substantial part is available at no cost, to make this approach happen. The leading partners of this firm

Sustainability ustainability ustainability

58

have strengthened the approach in dozens of academic articles and books. The fact that their approach is rather closely attached to their consulting practice does limit its dispersion among other practitioners and academics.

Literature

Buytendijk, F. (2010) Dealing with Dilemmas: Where Business Analytics Fall Short, New York, John Wiley.

Hampden-Turner, C. (1990) Charting the Corporate Mind: Graphic Solutions to Business Conflicts, New York, The Free Press.

Trompenaars, F., Woolliams, P. (2009) ‘Towards a Generic Framework of Competence for Today’s Global Village’, in: The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence, ed. D.K. Deardoff, Thousand Oaks, Sage.

- « Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- Next »