Author Archives: Infinite Ideas

Top 10 management models for your business: #4 Blue Ocean Strategy

16 July 2014 by Infinite Ideas in 100+ Management Models, Business and finance

by Fons Trompenaars and Piet Hein Coebergh, co-authors of 100+ Management Models.

Problem Statement

How can we create a long-term plan for sustained competitive advantage by focusing on new markets, without focusing on competition?

Essence

Kim and Mauborgne developed their Blue Ocean strategy in 2005, building on earlier

publications that also explored the insight that an organization should create new demand in an uncontested marketspace, or a ‘blue ocean’, where the competition is irrelevant. In blue oceans, organizations invent and capture new demand, and offer customers a leap in value while also streamlining costs. The central idea is to stop competing in overcrowded industries, so-called ‘red oceans’, where companies try to outperform rivals to grab bigger slices of existing demand. As the space gets increasingly crowded, profit and growth prospects shrink because products become commoditized. Ever more intense competition turns the water bloody. Blue Ocean strategies result in better profits, speedier growth and brand equity that lasts for decades while rivals scramble to catch up.

How to use the model:

The authors provide many examples of businesses that have created new markets (blue oceans) and present a model for crafting supporting strategies.

- Eliminate factors in your industry that no longer have value;

- Reduce factors that over-serve customers and increase cost structure for no gain;

- Raise factors that remove compromises buyers must make;

- Create factors that add new sources of value.

In addition, Kim and Mauborgne list a number of practical tools, methodologies and

frameworks for formulating and executing blue ocean strategies, attempting to make the creation of blue oceans a systematic and repeatable process. In their 2009 article ‘How Strategy Shapes Structure’, Kim and Mauborgne stress the importance of alignment across the value, profit and people propositions, regardless of whether one takes the structuralist (traditional competitive, Porter-like) or the reconstructionist (blue ocean) approach to strategy.

Results

Blue Ocean strategy should result in making the competition irrelevant. Therefore,

organizations need to avoid using the existing competition as a benchmark. Instead, make the competition irrelevant by creating a leap in value for both your organization and your customers. Another result should be the reduction of your costs while also offering customers more value. For example, Cirque du Soleil omitted costly elements of traditional circuses, such as animal acts and aisle concessions. Its reduced cost structure enabled it to provide sophisticated elements from theatre that appealed to adult audiences – such as themes, original scores and enchanting sets – all of which change from year to year.

Comments

The logic behind Blue Ocean strategy is counter-intuitive, since blue oceans seldom result from technological innovation. Often, the underlying technology already exists and blue ocean creators link it to what buyers value. Furthermore, organizations don’t have to venture into distant waters to create blue oceans. Most blue oceans are created from within, not beyond, the red oceans of existing industries. Incumbents often create blue oceans within their core businesses. A similar idea was put forward by Swedish management authors Jonas Ridderstråle and Kjell Nordström in their 1999 book Funky Business. Blue Ocean strategy is an inspiring way to look afresh at familiar environments with a view to finding a competitive edge. Unfortunately, most companies have marketing and strategy departments that look for benchmarks to be inspired by and copy rather than trying to be different.

Literature

Kim, W.C., Mauborgne, R. (1997) ‘Value Innovation – The Strategic Logic of High Growth’, Harvard Business Review, January/February, pp. 103–112.

Kim, W.C., Mauborgne, R. (2004) ‘Blue Ocean Strategy’, Harvard Business Review, January/February, pp. 71–79.

Kim, W.C., Mauborgne, R. (2009) ‘How Strategy Shapes Structure’, Harvard Business Review, September, pp. 72–80.

RoboFuture? Ten questions about machine intelligence

11 July 2014 by Infinite Ideas in Business and finance, Codebreaking our future

by Michael Lee, author of Codebreaking our future

[Originally published as a blog on the World Future Society website]

Ever since HG Wells wrote The War of the Worlds in 1897, various works of science fiction have speculated about the take-over of humanity by advanced robots or machines. Inventor and futurist Ray Kurzweil has gone several steps ahead of science fiction by working out an elaborate philosophy and pathway to a future governed by machine intelligence.

Kurzweil postulates that the Singularity will happen in 2045 when “the pace of technological change will be so rapid, its impact so deep, that human life will be irreversibly transformed” [Kurzweil, R (2005): 7]. It will represent, he claims, the “culmination of the merger of our biological thinking and existence with our technology…There will be no distinction, post-Singularity, between human and machine or between physical and virtual reality.” [Kurzweil, R (2005): 9] The non-biological intelligence created in the year of the Singularity, he states, will be one billion times more powerful than all human intelligence today [Kurzweil, R (2005): 136].

For computer scientist and science fiction author, Vernor Vinge, the core of the Singularity would be “the creation of greater-than-human intelligence” [More, M. & Vita-More, N (2013): 366] at which point all human rules will be thrown away in the face of an “exponential runaway beyond any hope of control” [More, M. & Vita-More, N (2013): 366]. After Singularity, Vinge and Kurzweil both proclaim, we’ll wake up in a radically new Post-human era.

I have several philosophical, logical, ethical, historical and futurological problems with the concept of the Singularity (which I will explore in future blogs) but today I simply want to adopt a common-sense approach. I want to ask 10 questions about machine intelligence. Readers can then answer each one as they see fit. The idea is to highlight the nature of machine intelligence compared to human consciousness.

While information technology has already attained unbelievable and revolutionary utility in today’s world, human intelligence, in my view, is far superior in virtually every facet to the intelligence within computer systems except for the processing, aggregating, calculating, storing and distribution of data at blindingly fast speeds. There have been several decades of worldwide research and development in the field of computers and so it is fair game to dig deep, at this juncture, as to the kind of intelligence which has actually been produced by computers in practice.

Here they are, then, ten questions to ask any man-made machine:

- Has machine intelligence ever independently produced an original idea, theory, philosophy or discovered any new principle or law of existence? This question concerns the capacity for sustained, original, creative thought.

- Has machine intelligence ever produced a unique, non-programmed story or created any imaginative literary work? This question relates to the power of imagination.

- Has a computer ever spontaneously said “I love you” and meant it? Q3 is about personal, real-time communication.

- Has a computer ever said “I’m sorry” and meant it? This question relates to empathy, the skills of listening and emotional intelligence in general.

- Has machine intelligence ever invented or coined a new word or term? Q5 concerns original linguistic talent.

- Has machine intelligence ever made an independent, non-programmed decision about how to act based on conscience? This question is about ethics and a sense of justice.

- Has a machine ever come up with a solution to a tricky social problem, solved a crime or adjudicated in a complex legal dispute? Q7 relates to the powers of deductive reasoning and lateral thinking.

- Has technology itself ever invented new technology, that is, have machines ever produced new types of machine no human had previously thought of? This question touches on the ability to be truly inventive.

- Has a machine ever had a religious or spiritual experience, an epiphany or eureka moment, said a non-programmed prayer, exercised faith or known awe and wonder? Q9 is about human spirituality.

- Has a machine ever made a spontaneously, personally motivated, non-programmed exchange with another being, whether some form of trade or extended social interaction? This question relates to the ability to engage in complex social, economic and political activity as a social being.

Aside from investigating the many technical and philosophical questions relating to the evolving interface between human and machine intelligence, these ten common-sense questions show it would be well-nigh impossible to mimic human consciousness and intelligence, let alone recreate, upload and surpass it, as proposed by Kurzweil.

Besides, do we really want to hand over control of civilization and human destiny to machinery?

Don’t we want to use, rather than become, technology?

Note: please feel free to send answers to any of these “ten questions to ask machines” to michael@futurology.co.za.

Acknowledgments

Kurzweil, R. 2005. The Singularity is Near – when humans transcend biology. London:Duckworth.

More, M. & Vita-More, N, ed. 2013. The Transhumanist Reader. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

New edition of 5,742 Days calls for drugs to be legalised and regulated

7 July 2014 by Infinite Ideas in 5742 Days, Lifestyle

Martha Fernback was 15 years old when she died on 20 July 2013 after swallowing half a gram of MDMA powder (more widely known as ecstasy). Since then her mother Anne-Marie Cockburn has suggested that the criminalisation of drugs contributed to her death.

At Martha’s inquest in Oxford in June Anne-Marie made her strongest call yet for senior politicians to enter into dialogue regarding fundamental reform of UK drug policy. After the inquest she invited Theresa May, Norman Baker and Yvette Cooper to “start a sensible dialogue for change, from prohibition to strict and responsible regulation of recreational drugs. This will help to safeguard our children and lead to a safer society for us all by putting doctors and pharmacists, not dealers, in control of drugs.”

Now a new chapter in the anniversary edition of Anne-Marie’s heartbreaking book 5,742 Days: A mother’s journey through loss brings the story up to date with the sentencing of the youth who supplied the MDMA, her public forgiveness of him, and her now public position that drug supply has to be taken out of the hands of criminals and given to pharmacists and GPs. The public response to Anne-Marie’s story has been incredible. She has received letters from all over the world, from prisoners doing time for drug smuggling, members of the House of Lords, other bereaved parents, to worried parents who have their own teenagers to contend with. It is for those teenagers that she has started her campaign. She writes:

“What is crystal clear to me now is that strict and responsible regulation of drugs is vital. This means taking drugs out of the hands of dealers and treating them in the same way as pharmaceuticals. Licensed drugs are labelled, ingredients are listed and necessary dosage information is provided.

Under prohibition, it is impossible to fully educate people as there is no way to tell what drugs contain, but despite this, many people are still willing to take risks.

It is important to stress that we need to do what we can in order to deter young people from taking drugs. However, had Martha known that what she was about to take was 91% pure, she would probably have taken a lot less, in fact I’d go as far as to say that she might still be alive.

Martha wanted to get high, she didn’t want to die. No parent wants either, but there’s one of those options that’s preferable to the other.”

For further information contact:

Catherine Holdsworth: catherine@infideas.com

5,742 DAYS

A MOTHER’S JOURNEY THROUGH LOSS

(Special 1st Anniversary Edition)

Anne-Marie Cockburn

£9.99 | Publication date: 20 July 2014 | ISBN: 9781908984333

Paperback | 198 x 129mm |174pp | Published by Infinite Ideas

Notes for editors

As a legacy of Martha’s death, Anne-Marie set up a website to encourage others to become involved in safeguarding the lives of young people: http://www.whatmarthadidnext.org/

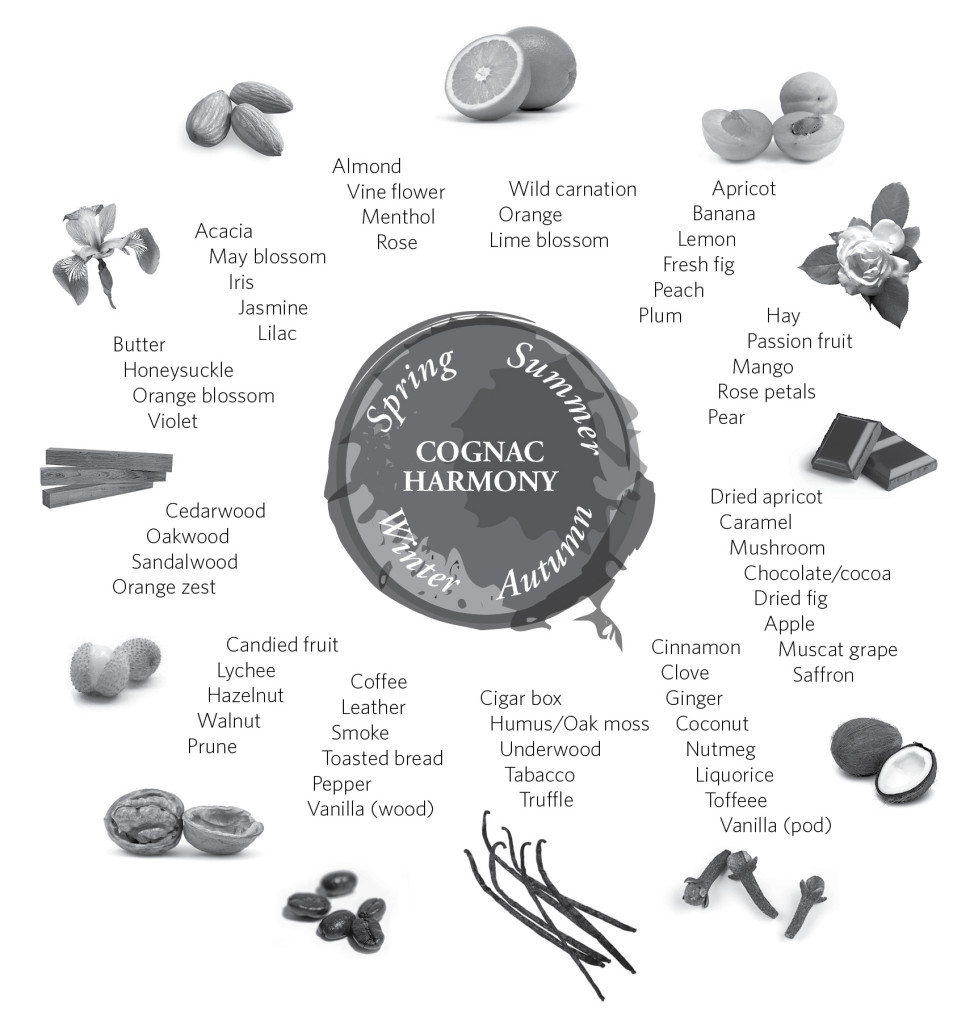

The cognac aroma wheel: your guide to cognac harmony

4 July 2014 by Infinite Ideas in Wine and spirits

This infographic is taken from Cognac, by Nicholas Faith, who has also written Nicholas Faith’s guide to cognac, which you can download free here. Both guides highlight the extraordinary range of cognacs available and will teach even the most clued-up cognac fan a few things about their favourite drink.

The great thing about cognac is the complexity of its flavours, which alter according to the seasons and the more mature the spirit, the better. See if you can spot any of these flavours the next time you have a glass:

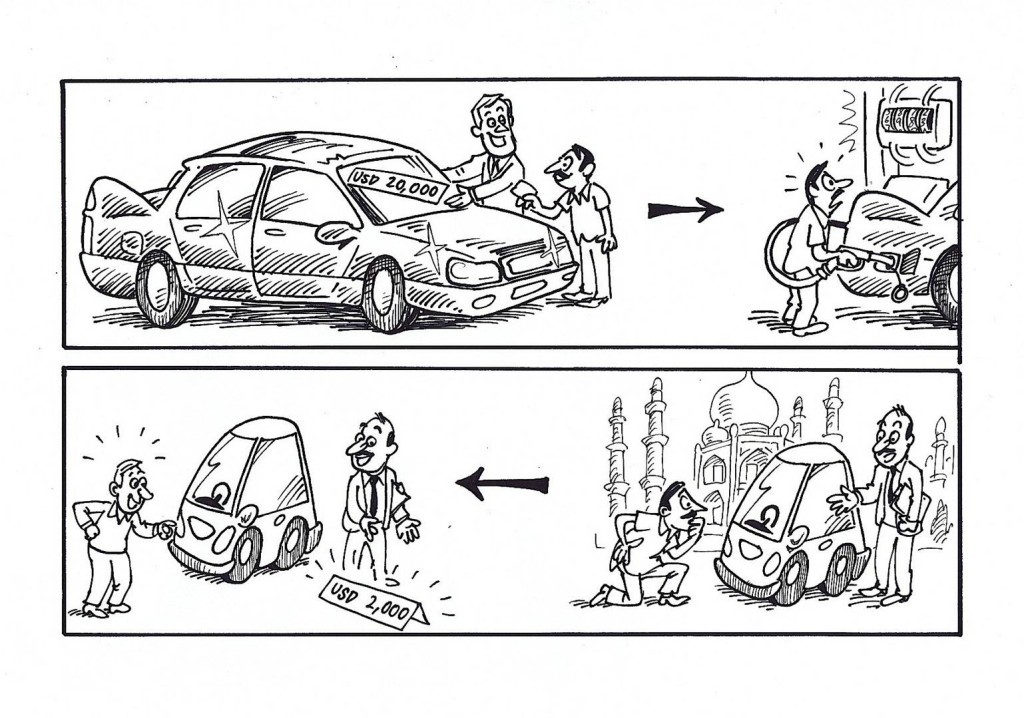

Top 10 management models for your business: #3 Reverse innovation

2 July 2014 by Infinite Ideas in 100+ Management Models, Business and finance

by Fons Trompenaars and Piet Hein Coebergh, co-authors of 100+ Management Models.

Problem Statement

How can reverse innovation create growth?

Essence

Vijay Govindarajan claims that the need and eagerness in emerging markets for sustainable growth creates an environment for innovation that is superior to the environment in more affluent countries. Govindarajan observes the following evolution: from globalization (richer countries that export what they use themselves) came glocalization (adaption to local needs on a global scale), followed by local innovation (emerging markets increasingly innovate themselves) which is making way for reverse innovation (emerging markets dominate innovation).

Reverse innovation is also called trickle-up innovation or frugal innovation. Govindarajan’s approach builds on Christensen’s theory of how innovation can be disruptive and C.K. Prahalad’s notion that there is a fortune to be made at the bottom of the social pyramid. Govindarajan served as the first professor-in-residence and chief innovation consultant at General Electric, some of the stories that illustrate reverse innovation were developed there, and supported by CEO Jeff Immelt.

How to use the model:

Govindarajan and Trimble’s Reverse Innovation Playbook (2012), covers nine rules ‘that will guide your innovation efforts’, in three categories, that can be summarized as follows:

- Strategy: To grow in emerging markets, innovate, not simply export; grow from innovations in emerging market to other emerging markets; beware of small but fast growing companies in emerging markets.

- Global organization: Move resources to where growth is; create a reverse innovation mindset; focus in these markets on growth metrics.

- Project organization: Stimulate an entrepreneurial ‘start-up’ spirit; leverage resources through partnerships; resolve critical unknowns quickly and inexpensively.

In addition, the Reverse Innovation Toolkit (2012) provides several practical diagnostics and templates to move reverse innovation forward in a company.

Results

Working with the Reverse Innovation Playbook and the Reverse Innovation Toolkit helps creative thinking about unconventional ways to innovate and grow. Evidence that supports this reverse-thinking model is mainly based on how multinational companies operate.

Comments

Like C.K. Prahalad’s theory of how a fortune can be made at the bottom of the pyramid, Govindarajan’s model has received criticism that the theory is not very specific in its approach and that there are only a few showcase examples, in a couple of big companies, to prove the concept, mainly from India and China. In addition, it is not completely unheard of for innovations from emerging markets to become successful, even in richer countries. That does not reduce the challenge that remains for rich countries of finding new ways to grow; in any scenario, this will increasingly be done with the emerging economies. Govindarajan presents a roadmap that at least has the power to take a radically different look at how most (Western) countries do business.

Literature

Govindarajan, V., Trimble, C. (2012) Reverse Innovation: Create Far from Home, Win Everywhere, Boston, Harvard Business Press.

Immelt, J.R., Govindarajan, V., Trimble, C. (2009) How GE is disrupting itself, Harvard Business Review, 87.10, pp. 56–65.

Mahbubani, K. (2013) The Great Convergence: Asia, the West, and the Logic of One World, New York, Perseus.

Is God a futurist?

24 June 2014 by Infinite Ideas in Business and finance, Codebreaking our future

by Michael Lee, author of Codebreaking our future

After reading the title of this blog, you may well be asking two questions: ‘Who is God?’ and ‘What is a futurist?’.

Believers in God know in whom they believe, while for those who don’t have religious beliefs, God is more like the Hypothetical One they don’t acknowledge as real. So let’s move on to the slightly less speculative question of the two, namely, ‘What kind of beast is a futurist?’

In the broadest sense, a futurist studies, analyses and forecasts the future in a disciplined, methodically sound way. The futurist’s currency is foresight, a systematic anticipation of the shape, structure and character of the emerging world. For many theoretical and historical reasons, the study of the future is still a sleeping giant.

In my view, systematic anticipation of the future, which I prefer to call futurology, is the next great science. But that is another topic covered in other blogs and published work. This blog is about God and the future.

We all remember that Einstein claimed that God does not play dice with the world and most readers will also know that Newton was just as deeply interested in theology as he was in physics and mathematics, possessing over two dozen Bibles at the time of his death. And what all science unquestionably shows is that the universe operates intelligently, following laws of nature and evolution. So one can either conclude that such intelligence of design and lawfulness of behaviour derives from a superior intelligence we call God or has emerged spontaneously from nothing/something. Each person makes his or her own determination.

As a futurist, what’s important is the extent to which the way in which science has modelled the universe may have enabled us to make rational predictions about future states. Mathematical genius Pierre-Simon de Laplace wrote in his ground-breaking 1814 essay, A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities : ‘Present events are connected with preceding ones by a tie based upon the evident principle that a thing cannot occur without a cause which produces it … We ought then to regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its anterior state and as the cause of the one which is to follow … The regularity which astronomy shows us in the movements of the comets doubtless exists also in all phenomena.’[1]

Since we are focusing here on God (or the Hypothetical One, if you would prefer) and the future, one might want to carry out a futurological exercise predicting what is likely to happen to religion – and the forces and institutions of religion – throughout the remainder of the twenty-first century. Using Laplace’s logic of probability, we would need to start by looking at the past and present state of religion in the world – it’s evolutionary trajectory – and then globally contextualize that pattern over time within the multiple dimensions of our world – social, cultural, demographic, political, environmental, economic, etc. So one would evolutionize and contextualize the data about religion as the basis for futurological conclusions.

In studying the future of religion in this way, we’d get glimpses into the future of God and his role in our world over the next few generations. That would require a major in-depth study well beyond the scope of this blog. But we can certainly provide an appetizer. Then an answer to the question posed in the title will be offered.

The most surprising fact about religion today, especially for those who live in largely secular Western societies from North America to New Zealand, from Europe to Australia, is that religious belief in the world as a whole is growing quite strongly, while the growth of non-religious belief has fallen well behind the average rate of global population growth, that is, the role of secularism is declining, despite the immense impact of Western-style economic and cultural globalization.

First, let’s check out the facts about human belief in today’s world (as at June 2010).

World population distribution of belief systems, with current annual growth rates*

|

Belief system |

Percentage of world population |

Current annual growth rate in belief system’s population size |

|

Christianity |

32.29% |

1.2% |

|

Islam |

22.90% |

1.9% |

|

Hinduism |

13.88% |

1.2% |

|

Non-religious |

13.58% |

0.7% |

|

Buddhism |

6.92% |

1.3% |

|

Chinese religions |

5.94% |

0.0% |

|

Ethnic religions |

3.00% |

0.6% |

|

Sikh religion |

0.35% |

1.4% |

|

Judaism |

0.21% |

0.3% |

|

Other |

0.32% |

N/A |

In the table above, only belief system population groups growing at a rate higher than 1.2% are growing faster than the world’s population. Non-religious people make up only 13.58% of the world’s population and that slice of the global pie is declining. This means that decades of economic and cultural globalization by a largely secular West have not brought about a concomitant, commensurate spread of non-religious belief.

The four largest religious belief system groups, namely, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism, together make up 75.99% of the world’s population, clearly a substantial majority.

In a nutshell, then, belief systems of the world are divided up as follows:

Top four religions by size = 75.99%

Non-religious population = 13.58%

Other = 10.43%

Figure 1: Comparative size of religious and non-religious populations in the world (2010)

Figure 1 shows that the Hypothetical One is not in any danger of being forgotten any time soon.

Furthermore, the future of religion will almost certainly be reinforced by a fundamental and intensifying global demographic trend, namely population decline. Depopulation is now occurring in many nations across the world. Dr. Phillip Longman, demographer and author of The Empty Cradle (2004) points out that global fertility rates are half what they were in 1972. It is thought that total human population may peak in 2050 at nine billion and thereafter decline. Bearing in mind that the human replacement fertility rate is 2.1 children per women, it’s alarming that 62 countries, making up almost half the world’s population, now have fertility rates at, or below, this rate, including most of the industrial world and Asian powers like China, Taiwan and South Korea.[2] At the start of the twentieth century, by contrast, the global fertility rate was higher than five children per woman of child-bearing age! The world’s population growth rate has fallen from 2% p.a. in the late 1960s to just over 1% today, and is predicted to slow further to 0.7% by 2030 and then 0.4% by 2050.[3] Most European countries are on a path to population ageing and absolute population decline[4]; in fact, no country in Europe is demographically replacing its population.[5]

Given this grim demographic picture, the role of pro-natal belief system population groups, including religious communities, is likely to become much more significant in the evolution of the human species. In the coming decades, humanity will be wrestling to avoid the disastrous socio-economic consequences of declining populations.

To halt population decline, radical change in values and lifestyle practices will eventually be needed. Human families, and their critical procreative role, will need to be strengthened.

The increasing influence of religion on society, of course, does not prove that God is a futurist, that is, a being who foresees the future in all its multi-dimensional complexity. Yet one of humanity’s first attempts to study the future was ancient prophecy. The prophets of the Old and New Testaments looked forward to a new world and, at times, to the projected end of the world itself. The Mayan civilization had deep insights into large-scale cycles of time, enabling them to make some far-reaching prophecies, including about a society which would one day fatally debase its environment.

The Bible is decisively future-facing in its outlook on the world, from Genesis (promising, for example, a long line of future generations from Abraham’s seed) to the overtly apocalyptic Book of Revelation. Many commentators believe Western civilization drew inspiration, in its rise to global power, from the Bible’s messianic, idealistic message, for example in the renowned Protestant work ethic geared towards building an earthly kingdom to the glory of God.

Given that religious belief systems are increasing in influence despite decades of secular economic globalization, it’s my perspective that the future of God looks promising. And, given that biblical theology is inherently prophetic and eschatological, one might even be tempted to say: the future of a futuristic God is bright.

To many in the world, frightened by religious extremism such as seen in the recent ISIS rampage across Iraq, this spectre of ascendant religion in decades to come may not appear to be good news. There is time, however, to inculcate rationalism, central to the objective discipline of futurology, within the public domain of shared common reality, in order to temper the emotional excesses displayed by the warped politics of some radical brands of religion. We need to move beyond ideology in public governance towards science as the great problem-solver. Slowly, I sense, a giant new science, with deep philosophical roots in the human past, is awakening.

Acknowledgments

Laplace,P.S. 1814. A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities. Cornell University Library.

Longman, P. 2004. The Empty Cradle. New York: Basic Books.

Magnus, G. 2009. The Age of Ageing. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia).

Mandryk, J. 2010. Operation World (Seventh Edition). Colorado Springs: Biblica Publishing.

*Data taken from the Seventh Edition of Operation World based calculated at June 2010

[1] Pierre Simon de Laplace, A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities

[2] Magnus, The Age of Ageing (2009) 40.

[3] Magnus, The Age of Ageing (2009) 33.

[4] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 61.

[5] Longman, The Empty Cradle (2004) 177.