Author Archives: Catherine Holdsworth

Understanding business finance

4 June 2014 by Catherine Holdsworth in Business and finance

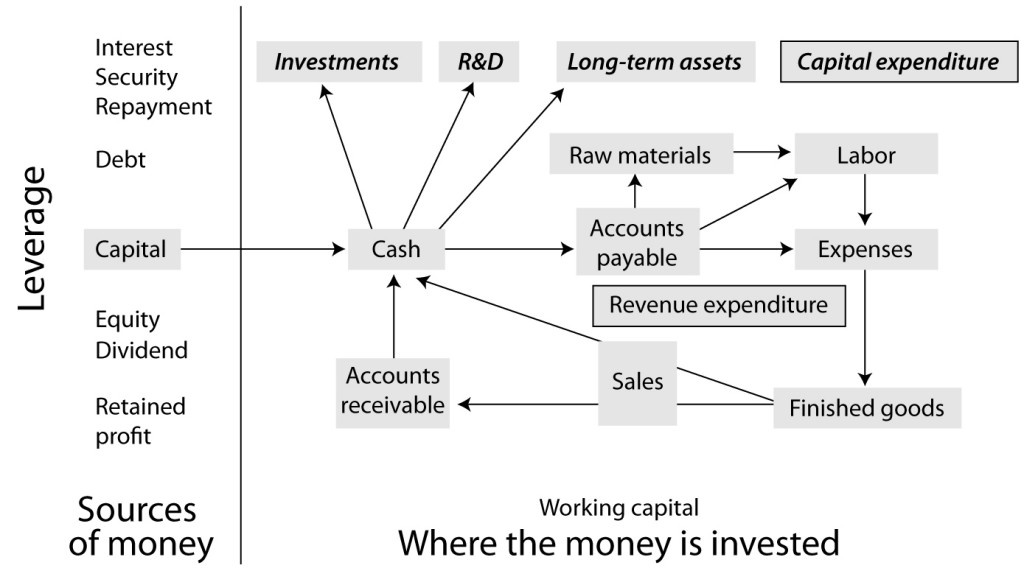

To understand business finance it is useful to have a diagram of how money flows round a business. Here is the business model:

Today we’re going to look at sources of money

The money used (or capital) in the business comes from stockholders (the owners) and lenders. Initially, the owners will pay for shares of stock and this money is invested in the business. As profits are earned, some of these profits are returned to the stockholders by way of dividends. If a company wishes to grow, it will retain profits within the business. These retained profits still belong to the stockholders but are being used to finance growth.

In the past, the term ‘stockholders’ funds’ was used to describe the amount of stockholders’ money invested in the business. The modern term is ‘equity’. Equity is therefore made up of the stockholders’ initial investment plus retained profits. The company owes this money to the stockholders but has no obligation to pay it back.

A company can borrow cash from a variety of sources. In a small business, the owners will often provide loans to the company – sometimes at a low rate of interest. The line of credit from the company’s bank is a popular form of financing since the company can access cash according to the needs of the business. However, lines of credit will usually carry a higher rate of interest than a long-term loan.

There is a wide range of other financial institutions seeking to lend to businesses. For the purposes of this book about basic finance, we will consider only the straightforward case where the loan is for a fixed term.

The implications of these two sources of money are different. In one sense, money from stockholders is cheaper. Return on the stockholders’ investment comes in the shape of dividends that are normally paid twice a year. In the early stages of a business the owners may very well drop the requirement for dividends and allow the managers to retain all the profits to allow them to grow the business. At that stage the money could be said to be free.

There is also no need for the managers to plan to have the cash to buy back the stock; in practical terms the money is in the company forever. The only downside in using stockholders’ funds to get a major business going is the cost of raising money in this way, since lawyers and accountants don’t come cheap. Another problem is that the business has to find someone willing to take the risk of putting money into an enterprise which, who knows, may fail. If the business does fail the owners lose all the money they have invested. It is this risk of failure which makes stockholders demand, in the long term, that their overall returns should be higher than the providers of loans. They get this return through the growth of dividends that the company pays out. In the long term, of course, if the company’s stock is traded on a stock market exchange the stockholders are hoping that the price of the shares will go up.

Loan finance (usually referred to as debt) is cheaper to arrange. Banks and financial institutions assess the risk of the company, make loans and charge an interest rate to reflect the perceived risk. It seems reasonable that they should tailor their interest charges to protect themselves against the risk of default; the problem is that a business in dire straits and in desperate need of cash has to pay more to get it – adding to the downward spiral.

Also, with debt, don’t forget, you have to plan how you’re going to repay the money within the agreed timescale.

Leverage

Leverage is a term that accountants use to confuse people. It is used in a variety of situations but always has the same implication. The easiest way to explain leverage is to describe a familiar situation. Suppose I buy a house for $100,000 with a 90% interest-only mortgage. I have put in $10,000 of my own money and that is my ‘equity’ in the house. Consider what happens if the value of the property goes up by 10%.

| Original position | New position | |

| Value of house | $100,000 | $110,000 |

| Mortgage | $90,000 | $90,000 |

| Equity | $10,000 | $20,000 |

The value of the property has gone up by 10% but my equity has gone up 100%. Excellent: easy money! The risk, of course, is that the price of the property may fall by 10%, in which case all of my equity is wiped out. If the value falls further, then I am into the position known as negative equity – note how financial terms are often used in everyday life.

The effect of leverage is to multiply my gains. In this case a 10% increase in the value of the house gave me a 100% increase in equity. Leverage is 10x (ten times). Notice that this multiplier can be applied to any percentage change in the value of the house. So, for example, a 25% increase in the value of the house in our example will give a 250% increase in equity.

In the next blog we’ll look at where the money is invested.